27

მაისი

2022

27

მაისი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

ხუთშაბათი,

19

აპრილი,

2012

ხუთშაბათი,

19

აპრილი,

2012

ხუთშაბათი,

19

აპრილი,

2012

ხუთშაბათი,

19

აპრილი,

2012

Anyone who has seen an old American classic “Best Years of Our Lives” (1946) probably remembers the scene where one of the protagonists, Al Stephenson, a banker who just returned from the war in the Pacific, tells his incredulous colleagues: “Our bank is alive. It’s generous. It’s human. We are going to have such a line of customers seeking – and getting - small loans, that people may think we are gambling with the depositors’ money. And we will be. We will be gambling on the future of this country”

This speech neatly summed up the prevailing mood of the post-war times – rebuilding an economy after a long stagnation or war requires an element of calculated risk. Without banks willing or able to take on such risks, the economy’s chances are poor. Innovation and entrepreneurship cannot survive without access to finance. Of course, in the aftermath of the 2008 global credit crisis, we also understand what it means to be complacent about risk. We understand that the financial system must always walk the tightrope between excess exuberance and excess caution.

Few people, I think, would disagree that in Georgia today the signs of economic renewal are visible and the atmosphere of change is palpable. But what can we say about the “financial mood” in the country today? The numbers, unfortunately, do not tell an optimistic story.

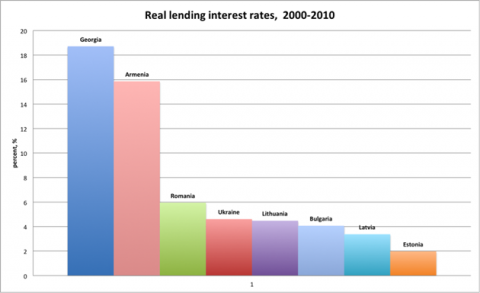

The real lending interest rates are some of the highest among the East European and Central Asian developing countries. Such high lending rates imply a lack of borrowing and low investment.

In part, high-interest rates could be explained by low levels of domestic savings (the issue discussed in my previous post “The Georgian Consumption Puzzle”). After all, if banks are short on deposits, they have to charge higher rates on borrowing, even if there are many viable and profitable business projects around.

Although, if domestic savings were the main constraint, we would expect to also see high-interest rates on deposits – the result of competition among banks to attract loanable funds. The competition for deposits would be evidenced in low-interest-rate spreads (the difference between lending and deposit rates).

However, as the chart below shows, this is not the case in Georgia. The interest rate spreads are quite high (almost twice as high as the average in developing Europe and Central Asia).

What can account for such patterns? The most likely explanation is the banks’ perception of credit risk. If we measure risk in the standard way, as the difference between the prime lending rate (the rate banks charge their best customers) and the “risk-free” government bonds rate, then banks in Georgia are quite pessimistic about the credit risk profile of private borrowers.

Additional indirect evidence on the credit risk perception and borrowing constraint can be found in the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Enterprise Survey for Georgia, 2008. According to the Survey, small firms (5-19 employees) are required to provide collateral to secure a business loan in 93.3% of cases (In Eastern Europe and Central Asia this figure is 77.4%). The value of the collateral needed to secure the loan is 237.3% of the loan amount (as compared to the average of 135.2 for similar size firms in EECA countries). Small businesses in Georgia also identify access to finance as a major constraint in 43.7% of the cases (as compared to 25.3% average for EECA countries).

What is responsible for such apparent excess of caution on the part of Georgian banks? For now, I would like to leave this question open to discussion and comments. Let me just make an observation that rational optimism which would allow banks to “gamble on the future” of their country requires something more than just patriotism. First and foremost, it requires sound institutional frameworks to serve as the foundation for the belief that the bet on this future will pay off. Such institutions would allow the country to realize fully the potential and the promise of the years we are living through – the best years of our lives.