02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Thursday,

29

March,

2012

Thursday,

29

March,

2012

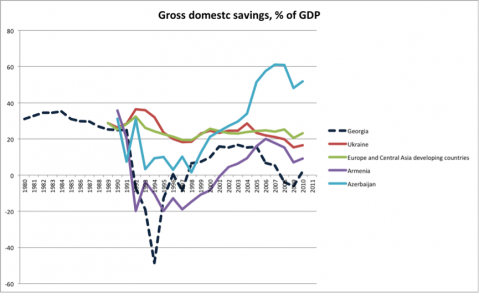

One of the current economic mysteries of the South Caucasus and the source of certain uneasiness on the part of world development organizations has been the significant rise in the recent years of the consumption to output ratio in Georgia.

The reason why such a trend can be worrisome is simple. High consumption rates, including private and government consumption, imply low domestic savings. Savings, in turn, are the source of funds for capital investment, one of the important engines of future economic growth.

In an open economy, the lack of domestic savings can be supplemented by borrowing from abroad. And indeed, many developing countries do just that – running high current account deficits from year to year, accumulating foreign debt. In Georgia, for example, the current account deficit stood at 11% of GDP in 2010, while external debt stock at 80% of GNI (World Development Indicators).

Yet, as long as a country’s borrowing is perceived as sustainable by foreign investors, there seems to be little reason for concern. Unless, of course, the sentiment among the investors changes abruptly, and the country experiences a “sudden stop”, or a sharp reversal of capital flows from abroad.

Needless to say, such events are not just unpleasant – they are very costly and highly disruptive to the country’s economy. Therefore, increasing the rate of domestic savings is perceived to be the key to sustainable investment and growth in the long run.

While macroeconomic stability indicators for Georgia are generally decent (moderate inflation rates, low share of short-term debt in the country’s total external borrowing, an improving government budget deficit trajectory, etc.), the concern about low domestic savings rate lingers on.

To be fair, the fall in domestic savings since 2005 cannot be blamed on the Georgian households alone.

Government spending as a share of GDP was on the rise since 2003 - the trend, which held for 5 years, reversing only since the global crisis.

And yet the growth of household consumption spending (to the level of about 80% of GDP) is surprising, given that the general trend in Georgia before the 1990s was close to that of Ukraine (around 60% of GDP) and another middle/low-income countries of Europe and Central Asia.

So what can account for such an increase? From a theoretical point of view, there are many possible answers, each warranting careful examination.

Yet, a few potential causes can be suggested or ruled out with a fair amount of confidence.

In theory, the lack of social security schemes (such as pensions, unemployment benefits), free medical care, and free higher education, would tend to increase savings. Clearly, this is not the case in Georgia. The current (minimal) social security provisions have not translated into high savings rates. Something else must explain the lack of domestic savings.

One of the explanations can lie in the higher expected lifetime income and higher income stability since the Rose Revolution, driven by relatively high growth rates of output.

The existence of borrowing constraints and rapid financial development also offers a potentially interesting explanation. After all, even a partial relaxation of the borrowing constraint faced by the households would tend to increase consumption and reduce savings.

Finally, could it be that Georgians are becoming more impatient to consume after years of economic deprivation, or, given the opportunity, are trying to catch up with the wealthier cohort of the population (see recent research on the issues of conspicuous consumption by Moav and Neeman, 2011 and thus changing their spending habits?

Undoubtedly, these possibilities must be carefully analyzed and taken into account by the policymakers concerned with economic stability and the sustainability of the country’s future growth.