21

მარტი

2022

21

მარტი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

პარასკევი,

09

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

09

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

09

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

09

ნოემბერი,

2012

A long season of high-stakes elections in Georgia, Ukraine, and now the United States is finally over. Once the last campaign posters are taken down, we may as well start asking: now what? Whether we like to admit it or not, the success of democracy is probably ill measured by the show of competitive campaigns or the transparency of the voting system. Instead, the success largely depends on how informed and engaged in the political process the general public remains after the elections.

This is something Ukraine has discovered the hard way since 2004. As engaged and passionate as people were during the 2004 elections, as sidelined and isolated from the political process they found themselves to be after the hard-won Orange Revolution victory.

In part, one may say, this happened because people had taken a step back from active political life and just waited for the democratic tree to start bearing the fruit of prosperity.

But is democracy really a key input into the production of a well-functioning economic engine? The evidence on the relationship between economic growth and democracy is mixed at best.

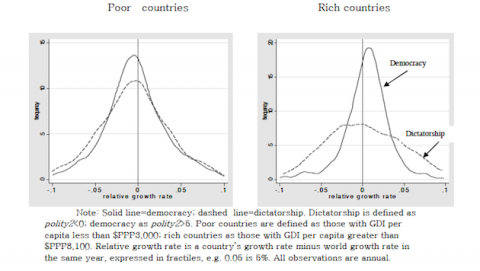

Branko Milanovic in his paper “The Modern World: The Effect of Democracy, Colonialism, and War on Economic Growth” points out that the growth outcomes of democratization can be very different for different countries. In fact, as the figure below (left panel) shows, poor countries are unlikely to grow faster than average, whether they are classified as democracies or dictatorships.

So, should we view democracy, not as an input into production, but rather as a luxury good enjoyed by the society only once it manages to achieve a certain level of prosperity? Perhaps, free speech and civil liberties are not facilitators of economic growth, but rather expensive indulgencies – like nice clothes or automobiles.

Looking at the right-hand side panel of the figure above, this does not seem to be the case. Rich democracies appear more likely to grow faster than the rest of the world, while rich autocracies are drawing from a very mixed bag of growth outcomes.

How do we reconcile these differences in the experience with democracy in rich and poor countries?

Perhaps it is best to think of democracy as neither a universal catalyst of growth nor a luxury consumption good. Rather, it may be likened to a sophisticated instrument that has the power to facilitate growth in the hands of those who know how to use it.

If at the core of mature democracy is the aspiration to actively participate in the process of decision making, the ability to take ownership of the political and economic agenda of the country, then it would not surprise me that democratization often produces the best outcomes in societies that are already well-to-do.

In such societies, people are more likely to already have a good idea of how to organize their economic lives more efficiently. Consequently, more likely to know what they want to achieve through the democratic process. In light of this, the hard work of learning to live with freedom and use it wisely starts only now, after all the campaign banners have been folded.