10

July

2023

10

July

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

10

October,

2015

Saturday,

10

October,

2015

Saturday,

10

October,

2015

Saturday,

10

October,

2015

During the last 12 months, the Georgian authorities have been conducting interesting experiments designed, so it seems, to test the resilience of domestic beer producers. In September 2014, the industry was hit by Article 171 of the Civil Code, prohibiting alcohol consumption in public places. The beer market, 97% of which is supplied by local producers, has immediately shrunk by 22% (in physical volume, see chart), in annual terms.

As if that were not bad enough, the Georgian Ministry of Finance had another surprise up its sleeve: a doubling of excise tax from 40 to 80 tetri per liter as of January 2015 (a major hike, considering that until then a liter of beer had retailed, on average, at less than 3.2 GEL).

The vocal public campaign conducted by Natakhtari, Zedazeni, and Castel resulted in a compromise: the tax was increased by only(?) 50%, from 40 to 60 tetri; also, the increase went into effect only on 1 March 2015, giving producers a bit more time to adjust stocks and investment plans.

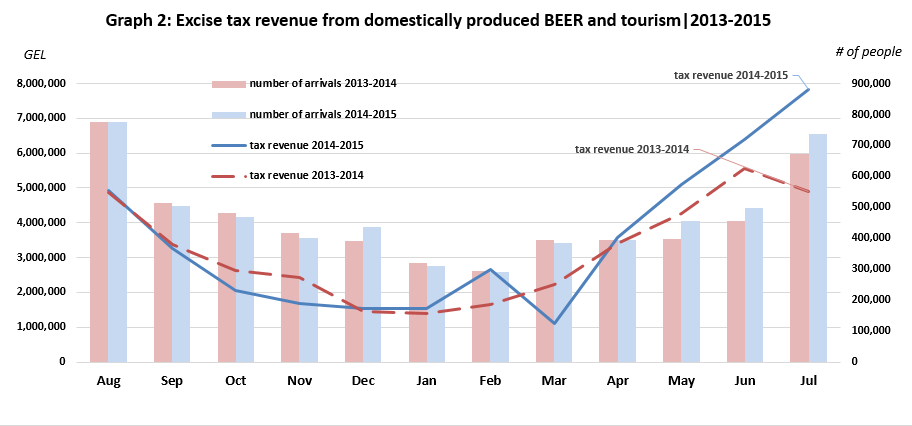

Still, by April 2015, the magnitude of the shock became apparent. Beer prices shot up by more than the amount of tax increase (by 37 tetri/liter or about 12%, on average, according to official CPI data) as producers scrambled to compensate themselves for shrinking sales. As a result, between April and June 2015 the market sank by almost 25% in physical volume and about 15% in sales (y-o-y). It took a major increase in tourism to (temporarily) bring the sector’s performance to a level exceeding its 2014 level in July.

The losses suffered by beer producers are, in fact, much greater given that the industry had been on a steady growth path prior to 2014. According to Nikoloz Khundzakishvili, Corporate Affairs Director of Natakhtari, the company had been projecting a 5% growth in 2015. The 15% drop in sales (and the total size of the beer market) thus represents a 20% gap in Natakhtari’s actual vs planned performance, prompting a management decision to reassign millions of lari from planned capital investment to operational expenses, such as advertising and marketing, to help recover some of the losses.

Georgian consumers most certainly did not appreciate higher beer prices. But, what about their health status? Whether intended or not, an increase in excise taxes could have triggered behavioral changes, reducing consumption of “bads” such as alcohol and tobacco, and, hence, leading to better health outcomes. The health benefits thus accrued to the general public could, in principle, justify losses inflicted on the private sector.

While theoretically plausible, such an optimistic view has little relation to the Georgian reality.

First and foremost, given Georgia’s rich chacha and winemaking traditions, consumers could easily substitute away from (taxed) manufactured alcohol to its excellent (non-taxed) informal equivalents. As the beer got more expensive, people simply went back to wine.

Second, public health was apparently of little concern for Georgia’s fiscal authorities. By setting a higher excise tax rate for stronger beers (e.g. 8%), they could have gently nudged people towards healthier consumption habits (as would be consistent with the EU Association Agreement agenda). Yet, as rightly noted by Transparency International, Georgian policymakers did not make any effort to do so.

Finally, if health were the desired policy objective, the government should have taxed wine (the excise tax on wine was abolished after the 2006 Russian embargo), which has a much higher alcohol content. Yet, for obvious political reasons, the excise tax on wine had not been re-introduced, allowing people to continue to indulge in cheap alcohol.

According to government statements, the hike in excise tax rates was expected to bring an additional GEL30-40mln in tax revenues in 2015, representing a 50%-60% increase over 2014. Based on the past and expected share of beer in total excise revenues, the extra revenue from beer should have been in the GEL 16-21mln range.

The reality is that, in the first 7 months of 2015, after the introduction of higher excise tax rates, the beer market has generated additional tax revenue of GEL 5.2 mln, which is, indeed, 20% higher in comparison with the same period of last year. According to our estimations – using past monthly consumption as a proxy for future beer consumption, and taking into account the beer market’s general contraction – till the end of 2015, the government will only be able to collect an additional GEL 4.5mln, bringing total extra revenue to GEL 10mln, or about 50% of the planned amount.

This could be considered a (partial) success, except that….

Let us recall that excise taxes revenues have been growing in all previous years in line with the market’s expansion. For instance, from 2013 to 2014, they grew by 18%, reflecting the increasing consumption of alcoholic beverages. Thus, if the beer market were left alone in 2015, it is highly plausible that excise tax revenues generated by this market would have grown by the same GEL 10mln, not counting potential increases in other tax categories (income, profit, VAT) related to increased employment and sales.

Finally, and most importantly, our calculations suggest that whatever extra tax revenues the government was able to generate in 2015 (largely thanks to the great performance of the tourism sector, see chart), they fell far short of the sum total of losses its policy inflicted on Georgian consumers (who were forced to pay higher prices and switch to other products) and the beer industry. The industry’s losses alone are roughly estimated at about GEL 15 mln, significantly exceeding the government’s extra revenues, implying great social losses.

Earlier this year we argued that the government’s decision to increase excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco as of January 1, 2015, would end up hurting the private sector without bringing any benefits. We wrote:

“The Government’s official aim was to increase budget revenues while harmonizing Georgia’s regulatory environment with that of the EU. Yet, the manner in which the whole process was rushed raises many questions. Georgian companies were not allowed any time to adjust their investment and production decisions, leaving them with excess capacity and losses. Furthermore, the level of excise taxes on alcohol was set at a level exceeding that of many European nations. This was decided without examining relevant demand elasticities, that is, the extent to which higher taxes will affect sales and budget revenues. In a country with rich traditions of in-home production of high-quality alcoholic drinks (that are not subject to excise taxes), demand for alcohol is likely to be quite a bit more elastic than in most European nations. After all, Georgian consumers can switch to homemade wine or chacha, spelling doom on the Georgian government’s plans to raise an extra 100mln GEL in excise tax revenue.”

What was merely speculation back in February 2015, appears to be corroborated by facts.