31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

05

June,

2017

Monday,

05

June,

2017

Monday,

05

June,

2017

Monday,

05

June,

2017

All over the world, the quest for technological innovation is proceeding with great intensity. Georgia is not an exception. While local universities are trying to build fab-labs (fabrication laboratories – small-scale workshops offering personal digital fabrication), the government has established the Georgian Innovation and Technology Agency (GITA) to support the creation of start-ups and tech companies. In addition, there are still a large number (more than 60) of still-operating former Soviet scientific institutions, either working independently or under different public and private universities. Despite such a large number of scientific Institutes, however, Georgia ranks usually quite low when looking at the number of scientific publications, and at the number of citations per article (as measured by the h-index), typically around the middle of the ranking and behind most eastern European countries. Furthermore, so far, investments in the innovation sector have failed to translate into success stories that contribute substantially to the development of the country and attract the majority of the younger generation. Only 27% of the bachelor and 20% of the master’s degree graduates have backgrounds in natural sciences or engineering1.

Amidst this apparently dismal landscape, however, there are a few stories that seem to be moving in the right direction. One such story is that of the George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology, and Virology (the Institute). The Institute managed to survive the traumatic transition period following the fall of the Soviet Union and to sustain its scientific profile around the world. With more than two dozen publications in international journals over the last five years, it is still a brand name around the world in its own sphere of research. The case of the Eliava Institute is becoming even more fascinating as it is slowly managing to commercialize its scientific research and contribute to the sustainable development of its business model.

For over 90 years now, the key research area of the Institute has been the selection and development of bacteriophages. The Institute is the only institution in the world with such a track record. Bacteriophages are viruses that attack specific bacteria while ignoring (and is therefore harmless to) the human (or animal, or plant) host. Unlike antibiotics, bacteria have a much harder time developing resistance against bacteriophages. Moreover, even if they manage to develop some resistance, because of the extremely large number of phages around us, researchers must just look for another phage against which bacteria have no immunity. As antibiotic resistance is increasingly becoming a problem in the modern world, the Institute, it seems, has found a very good niche for its operations.

A bit of history about the Institute can help better explain the essence of their success. The Institute was founded by two pioneers of bacteriophage research: Georgian George Eliava and French-Canadian Felix D’Herelle. The two scientists created a World Centre of Phage Research and Phage Therapy in Georgia. Unfortunately, after building the Institute, its Georgian founder became a victim of Soviet repressions and was executed in 1937. After his death, Prof. Felix D’Herelle never returned to Georgia. Despite this unfortunate series of events, however, bacteriophage research continued, becoming a viable alternative to the initially scarce supply of antibiotics behind the Iron Curtain. The Institute was very well endowed, funded, and managed by the central government of the Soviet Union. When Georgia became independent in 1991, during the transition period, the lack of funding became dramatic, endangering the physical survival of the Institute. Despite the great difficulties, however, the scientists from the Eliava Institute managed to protect most of the Institute’s heritage and slowly started to search for alternative sources of funding, applying for different grants and building international scientific collaborations and partnerships. In addition to scientific collaborations, the researchers broadened the Institute’s portfolio and revenue sources by providing diagnostic services and by producing bacteriophages for sale and for treating patients, creating one of the first successful examples of science commercialization in the history of independent Georgia. From the beginning of the 2000s people from around the world started coming to Tbilisi to be treated for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. All this helped the scientists at the institute to better understand which core services connected to their research had the greatest development potential.

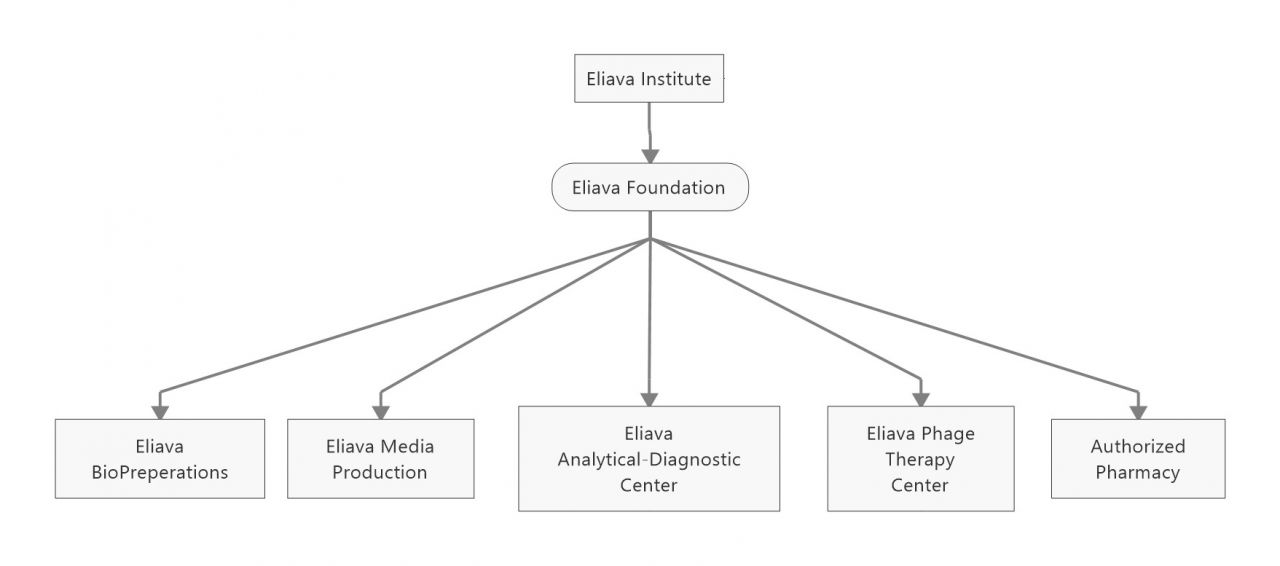

To ensure the sustainability of its activity and the provision of these services, the Institute started implementing a model for the commercialization of science-based on one used by the University of Wisconsin (The Wisconsin Technology Innovation Initiative). This model entails building up a consortium of for-profit organizations working under the umbrella of a non-profit foundation (in this case, the Eliava Foundation), that itself is founded by the institute and its scientists. Today the Eliava consortium consists of: (i) Eliava BioPreparations – manufacturing bacteriophages, (ii) Eliava Media Production – manufacturing of biological media, (iii) Eliava Analytical-Diagnostic Center – providing diagnostic services to patients, (iv) Eliava Phage Therapy Center – providing treatment services with specific bacteriophages, and (v) Eliava Institute Authorized Pharmacy – selling medications elaborated by the Institute and produced by BioPreparations.

Although the Institute has been successful in surviving the hardships of the transition period and came out of it with a working model of operations, the challenges it faces are not over yet. While the Institute is currently benefiting from revenues associated with the treatment of local and international patients, and from the local commercialization of its preparations, the potential revenues from this type of operations are relatively limited and do not allow for a substantial increase in scale, which is necessary for long-term sustainability. The next step for the Eliava Institute is, therefore, to capitalize on its international brand name and to bring its products and services to international markets. Putting bacteriophages on the global market is not an easy task, however, especially considering the strength of the – competing – antibiotics industry in developed countries. The Eliava Institute has been trying for more than a decade now to get through the bureaucratic procedures of the United States and of the European Union regarding the approval of bacteriophage therapy.

One of the things that could help would be obtaining support from the Georgian government to remove the existing obstacles to the commercialization of bacteriophages on global markets. Another initiative that could be of assistance is the promotion of bacteriophage applications in different areas (human health, agriculture, veterinary and others) inside Georgia.

A clear lesson that can be learned from the case of the Eliava Institute is that it is important to identify promising niches for the commercialization of products and services related to innovative scientific research, to help achieve sustainability of scientific research initiatives. The sale of products and services in profitable niches can both support scientific research and ensure the survival of the institution in the longer term, even in the absence of substantial public support, and constitutes a much more viable strategy in situations characterized by scarcity of public and private funding. This solution is also preferable to the expansion of public spending over areas in which there are no substantial comparative advantages. Another interesting lesson that can be learned from the experience of the Eliava Institute is that when an umbrella not-for-profit organization is founded to control for-profit activities conducted by the same scientists that work in the scientific institution (allowing them to retain control of the know-how and portions of the profits generated by their own research), they have a greater incentive to work for the success of the whole enterprise. A final lesson worth emphasizing is that, whenever an organization such as the one put in place by the Eliava Institute proves successful, the government should consider supporting its efforts to commercialize its products and services. This is not so much about “picking the winners” among the numerous “innovative ideas” in the country (which the government is not always in the best position to do), but about helping the “emerging winners” grow beyond their national dimension and reach international markets, potentially contributing simultaneously to the improvement of the scientific standing of the country, and to its economic development.

1 Most of these graduates hold degrees in computer science and mathematics.