31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

01

February,

2019

Friday,

01

February,

2019

Friday,

01

February,

2019

Friday,

01

February,

2019

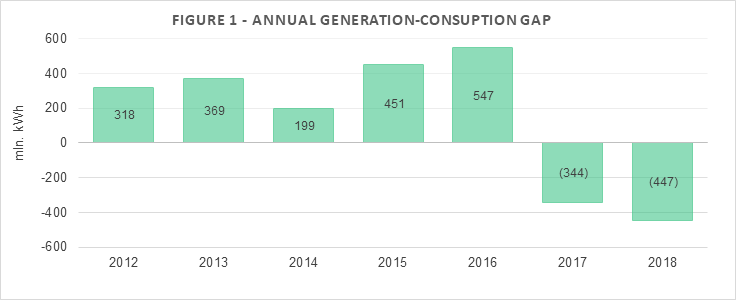

Looking at annual consumption and generation trends, from 2012-2016, it is clear that generation typically exceeded consumption. Consequently, the generation-consumption gap remained positive. However, in 2017 this trend reverted, and the electricity generated by local resources on the Georgian market was no longer enough to supply the local demand. As shown in Figure 1, the gap widened even further in 2018; with the negative gap increasing by 30% (from 344 mln. kWh in 2017 to 447 mln. kWh in 2018).

This significant reversal has motivated us to explore its causes and the subsequent implications to energy security.

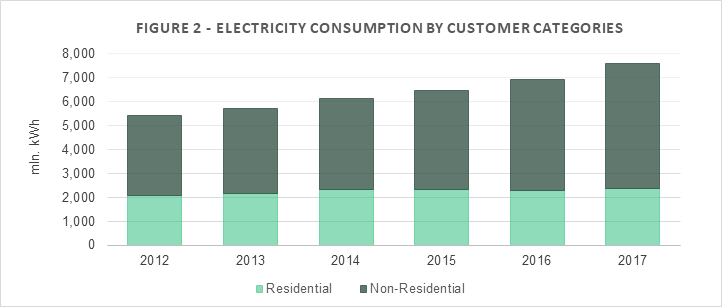

Firstly, we’ll begin by looking at electricity consumption. In 2017, total consumption increased by 8%, from 11,027 mln. kWh to 11,875 mln. kWh. Consumption continued to increase, albeit at a slower pace, in 2018, reaching 12,596 mln. kWh, which corresponds to a 6% increase in electricity use compared to 2017. In both years, the increase in demand originated mostly from the distribution companies (Telasi, Energo-Pro Georgia), and directly from the consumers.1 Within 2012-2017, according to the GNERC 2017 annual report, the greatest, and growing, share of the total consumption of the distribution companies arose from the non-residential sector (Figure 2). While in 2016 and 2017, the consumption of distribution companies grew at a historical rate (9%). Unfortunately, the data for 2018 is still unavailable. As direct consumers usually also represent large-scale commercial entities, it appears that the increase in consumption is indeed driven by the non-residential sector, which is likely to reflect increased economic activity in the country.

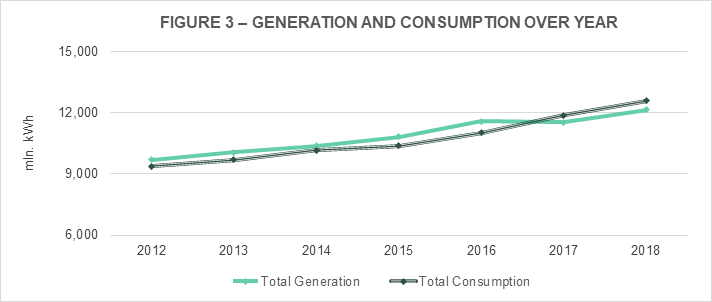

While electricity consumption has been steadily increasing, electricity generation has followed a different path. In 2017, it declined by 0.4%, from 11,574 mln. kWh to 11,531 mln. kWh (of which 79% was from hydropower plants (HPPs) while thermal power plants (TPPs) generated 19%). The decline in generation arose from reduced HPP (-2%) and TPP production (-0.1%). As a result, for the first time in five years, 2017 recorded a generation deficit. In 2018, Georgian power plant generation increased again, to 12,149 mln. kWh of electricity (from which 83% was from HPP, while the remaining 17% was from TPPs), which represents a 5% increase in total electricity generation compared to the previous year. The increase in generation came from HPPs (a 9% increase from 2017), rather than offsetting the decrease in thermal power and wind power (WPP) generation (-5% and -4%, respectively). However as consumption continued to rise, the increase in total internal generation was insufficient to provide for local demand (Figure 3). In reality, the gap widened, partially because TPP generation declined, while HPP generation increased. This implies that having a negative electricity balance, to some extent, was an active choice.

In a previous article, we highlighted how this phenomenon could relate to the lower cost of imports vis-à-vis thermal power generation.

Technically, Georgia could still cover all its electricity demand without importing a large amount of electricity, with the minor exception of certain technical imports, but should that make us feel more relaxed about the energy security of the country?

Not really. If we consider the years in which electricity generation exceeded electricity consumption, a significant part of generation was still provided by TPPs fueled with imported gas, thus it is clear that the current gap simply reveals a problem that has long existed. Even today, with almost 20% of the electricity generated by TPPs, the energy security issue is more severe than demonstrated by the electricity generation deficit.

In reality, both the initiation of thermal power plants – with the import of natural gas – and the import of electricity are a sign of energy dependence. Moreover, both sources of electricity and natural gas are mainly provided by the same trade partners, either Azerbaijan or Russia.

At this stage it is virtually impossible to imagine a scenario without energy imports (either electricity or the gas to power TPPs), furthermore, because HPP generation is characterized by considerable seasonality, Georgia is forced to import over the winter.

Yet, there are viable options to narrow Georgia’s energy dependence and, therefore, enhance its energy security:

• increasing the potential of electricity generation from renewables, possibly diversifying the internal generation sources (more wind and/or solar) to reduce import needs in the most problematic seasons;

• incentivize the demand side of the market to become more energy efficient (and, in some cases, at least partially self-sufficient).

It is important to now outline the policies and measures utilized by the supply side of the sector. In 2017, the Ministry of Energy listed its future investment projects, with 155 total projects (an installed capacity of 6,584 MW), out of which seven HPPs, with a total installed capacity of 68 MW, were implemented in 2018. It is noteworthy that the currently installed capacity is 4,812 MW, of which HPP provides 77.4%, while TPPs and WPPs deliver 22.1% and 0.5%, respectively. HPPs dominate generation, and in future projects, 62% of the total installed capacity will be associated with new HPPs. As for wind power, thermal power, and solar power plants (SPP), the proportions are as follows: 19%, 12%, and 8%, respectively (Figure 4).

If the country’s purpose is to reduce its dependencies and enhance energy security (keeping in mind the seasonality behind HPP generation), this reliance on HPPs might appear perplexing. The perplexity simply increases once one considers that the estimated time of commencement has only been indicated for conventional electricity generation sources (HPPs and TPPs). Whereas, the start dates of non-hydro renewable investment projects remain unclear. One hope is that the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP) will be expanded to accelerate the integration process of non-hydro renewable energy projects into the grid system and to cope with the issue of uncertainty in terms of investment profitability. Thus it would become effective at providing incentives to investors and reducing the risks associated with investing in renewable sources, thereby stimulating investments in the area.

On the energy-efficiency front, the news is hardly any more encouraging. Georgia should have already complied (by the end of 2018) with the Energy Efficiency Directive, 2012/27/EU. The directive requires EU countries to use energy more efficiently at all stages of the energy chain, from production to final consumption, in order for the EU to reach its 20% energy efficiency target by 2020. However, Georgia has yet to do so. Three steps are still necessary to achieve this goal. The first step includes the elaboration of the first draft of the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP). The aim of the NEEAP is to identify the measures and required policies needed to comply with EU standards. The next step covers the adoption of NEEAP and the elaboration of its primary legislation, the Energy Efficiency Law, the aim of which is to set the legislative basis for the implementation of NEEAP policies. The last step studies any modifications to the existing legislation and the development of secondary legislation. Georgia is currently still in the first stage of this process, and according to the responsible entities, the draft version of NEEAP is still being updated.

To conclude, it is still unclear whether Georgia will manage to address the problem of its electricity generation deficit (and improve energy security) in the short term. However, if we do not want to see a progressive reduction in the country’s energy security, including the deterioration of electricity accessibility and affordability, governmental action certainly should become more incisive and better focused.

1 The direct Consumers are Georgian Manganese, Georgian Water and Power, Georgian Servers, BFDC Georgia, Kutaisi Investments, Energo-Pro Georgia, Achara Enerji 2007 (Kirnatihesi).