31

მაისი

2023

31

მაისი

2023

ISET ეკონომისტი

სამშაბათი,

05

ივნისი,

2012

სამშაბათი,

05

ივნისი,

2012

სამშაბათი,

05

ივნისი,

2012

სამშაბათი,

05

ივნისი,

2012

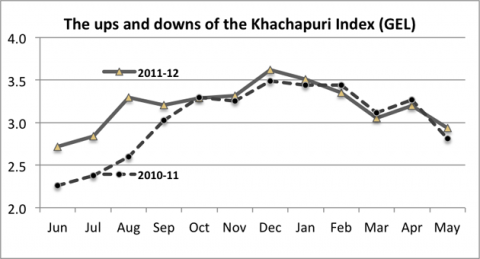

This week marks the first anniversary of the “ISET Khachapuri Index” in The Financial. During the last 12 months, our faithful readers have followed the ups and the downs of the index and learned many economics lessons in the process.

The sharp seasonal fluctuations of the Khachapuri Index are very much reflective of the state of Georgian agriculture: fragmented, unorganized, and underdeveloped. The roller coaster of agricultural production is no great fun for consumers and small Georgian farmers alike. When bringing their products to the bazaar in high season, farmers receive only a fraction of the price they would have received had they used greenhouses or cold storage facilities to extend the season. Yet, small farmers are too small and too poor to buy fodder and fertilizer, let alone build greenhouses. With each Georgian farmer minding his own (very small) business, the sector has essentially become a refuge for the un- or underemployed. It is certainly not able to compete internationally, both with the Turkish imports to Georgia and in the lucrative export markets.

One common way to overcome fragmentation in agricultural production is to promote farmer organizations that could undertake joint investment in machinery and equipment, procurement of inputs (seed, fertilizer, etc.), processing, branding, and marketing. Yet, successful farmer organizations are almost nowhere to be seen in Georgia. Sure, cooperation requires a common vision, mutual trust, and … excellent management skills. All of these can only be developed over time. Yet, an argument is sometimes made that Georgian village communities are inherently individualistic, a tendency only made worse by the history of forced Soviet collectivization. True?

Anybody driving from Rikoti tunnel down to Kutaisi will not fail to notice the large ceramics market next to the Shrosha village. The market, known among the locals as “Bogiri” (an old word for “bridge” in the Imeretian dialect), has been in operation during the last 70 years, ever since the construction of the East-West highway. Jointly operated by 60 Shrosha village families, Bogiri provides an interesting example of Georgian-style community-level cooperation, with all its cons and pros.

Of a total of 400 Shrosha households, about 120 are in the ceramics business. Some of them have a stake in Bogiri, others sell their products to Bogiri resellers, as well as other roadside markets, restaurants, and souvenir shops in Georgia. The land occupied by the Bogiri market is formally owned by the Zestaponi municipality, yet the elders of Bogiri perceive and manage the market as a joint enterprise. Since the physical location in the market is critical to sales (higher in the center, lower at the edges), a key collective arrangement concerns the assignment of locations (small rectangular on which clay products are displayed). Fairness is ensured through a weekly lottery, using real lotto game pieces numbered from 1 to 60! Accordingly, once a week each family is obliged to move with its entire merchandise. Inefficient, but fair.

The elders of Bogiri have been successful in designing and implementing many other collaborative arrangements as well. For instance, the 60 families abide by the agreed-upon rules on how to display their merchandise (smaller items in front, larger in the back). Rotation is used to provide security services: one family stays on a night shift – selling their own products and watching the rest. The 60 families are also quick to take collective action to lobby the local authorities. For instance, very recently they managed to block an attempt by one Shrosha family to break away from the pack and set up shop next to a water spring 100m away from Bogiri.

Surprisingly or not, the Shroshans are relatively lax on intellectual property rights and pricing. New non-traditional designs are immediately copied. Despite meek attempts to coordinate prices (by resellers facing higher costs), each family is free to set its own prices, and travelers can therefore engage in bargaining.

Yet, while providing a model of sustainable village-level cooperation, Bogiri has abounded with examples of collective action failures. For instance, the villagers could never agree on a joint investment in infrastructure or in the common brand. Imagine the travelers’ shopping experience in the presence of an improved parking lot, a restaurant, or a café (think of wine tasting from traditional Georgian earthenware as a sales-boosting tactic), yet none exist on site. Mind it that the 60 families would not oppose a private investment in a café (on which they could take a free ride), yet they cannot agree on a “joint venture” serving a common objective. Furthermore, until recently there was not even a road sign (!) inviting travelers to stop and shop for authentic Georgian pottery. The 60 families could not agree to jointly produce such a sign during their 70-year history of cooperation, including 20 years under a free market economy regime. The sign has been finally erected by the local Zestaponi authorities, perhaps as a result of successful collective lobbying by the Shrosha community.

The Shrosha experience suggests that the Georgian villagers are able to organize themselves when it is in their interest to do so. Yet, just like in the rest of rural Georgia, Shrosha’s version of bottom-up community organization has to be taken to the next level if it is to serve as an engine of modernization: facilitate investment in know-how and technology and raise productivity beyond a mere subsistence level.