31

მაისი

2023

31

მაისი

2023

ISET ეკონომისტი

პარასკევი,

30

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

30

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

30

ნოემბერი,

2012

პარასკევი,

30

ნოემბერი,

2012

We may recall that the Lazika city project has been proposed by the Saakashvili administration to accelerate the process of urbanization. A new city was suggested as a means of absorbing surplus rural population and thus paving the way for land consolidation and greater productivity in agriculture. No country, it was claimed, was able to modernize itself while maintaining almost 50% in rural employment.

Yet, if we look at the global statistics, Georgia is reasonably urbanized. With 53.2% of urban dwellers, Georgia is ranked 107 in the world, slightly behind Slovakia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Albania. Perhaps surprisingly for some, we have a larger share of the urban population compared to Romania, China, and Slovenia.

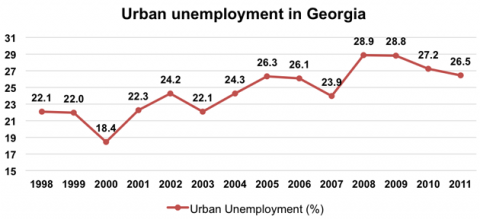

While Georgia is moderately urbanized by global standards, most Georgian cities appear to be oversubscribed by job seekers. Urban unemployment has been on the rise since the early 2000s, despite a temporary respite in 2006 and 2007. It is particularly high among youth, reaching up to 35%.

If anything, this seems to suggest that rather than engage in Lazika-type extravaganza projects, Georgia should emphasize rural, not urban development. Creating productive jobs in the countryside, whether, in agricultural processing, arts &crafts, tourism or other services may dramatically improve the labor market situation in Georgia’s cities and villages alike. And what’s particularly important, it may not require as much investment.

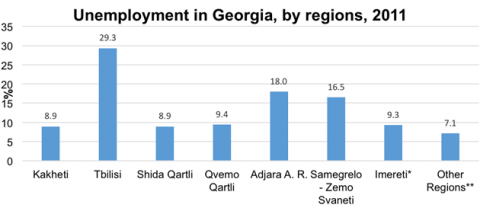

Another important fact to consider is that urban unemployment is unequally distributed across Georgian cities. It is in fact concentrated in less than a handful of cities, such as Batumi, Poti, and, of course, Tbilisi.

Despite having many people knocking on their doors, Georgian cities have not grown in the last 20 years. In fact, they lost population compared to 1989, the last year for which pre-independence data are available. The smaller towns lost some of their most able population to Tbilisi. In its turn, Tbilisi lost some of its labor and intellectual elite to Moscow and other migration destinations in the former Soviet Union and “further abroad”.

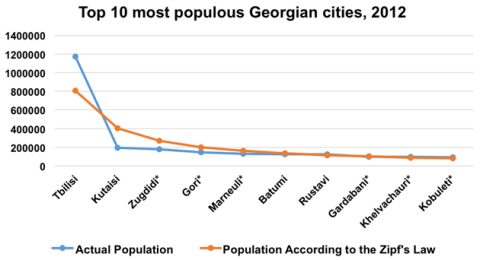

As a rule, the larger and richer cities lost less population and grew in wealth, potentially creating a vicious circle. For instance, Tbilisi lost only 8% of its population relative to 1989, compared to 12%, 14%, and 26% losses in Batumi, Kutaisi, and Telavi, respectively. The result today is that Georgia’s urban population is very unequally distributed across the major urban agglomerations.

Based on factual data from around the world, the famous Zipf’s law has it that the number of people in a city is inversely proportional to the city’s rank among all cities in a country. In other words, the biggest city is about twice the size of the second biggest city, three times the size of the third biggest city, and so forth. Yet, if we look at the Georgia data, Zipf’s law does not seem to hold. Tbilisi with its 1.17million is almost 6(!) times larger than the second most populous city Kutaisi (196.8 thousand). If we were to redistribute Georgia’s population in accordance with Zipf’s law, Tbilisi would have about 800,000 inhabitants, compared to 400,000 in Kutaisi, about 270,000 in Zugdidi, and so on.

We don’t want to be misunderstood. Urbanization is a good thing. The flow of people from sparsely populated rural areas towards highly productive and densely populated cities has been steadily progressing ever since the first cities appeared upon Earth. Georgia has been no exception.

The industrial revolution has greatly accelerated the process of urbanization: the global share of the urban population rose dramatically from 13% (220 million) in 1900, to 29% (732 million) in 1950 and to 49% (3.2 billion) in 2005. According to the UN World Urbanization Prospects report, it is likely to rise to 60% (4.9 billion) by 2030.

Even the ability to work at a distance from one’s colleagues in the Internet age is not going to change this fundamental trend. The process of urbanization is ultimately about bringing people and firms closer together. Urban agglomerations give rise to very significant gains in productivity because they provide a superior environment to exchange ideas and innovate; easy access to a greater variety of inputs and services; and better amenities such as schooling, healthcare, and entertainment.

A crucial point is this. From an individual migrant’s perspective, moving to a city is a lottery. Those winning can expect higher wages, better education opportunities, and access to better amenities. But just like with any lottery, not every migrant gets to win. Moreover, the probability of winning (let’s say, getting a good job) could be quite low if a massive exodus of the rural population occurs over a short period of time, similar to what Georgia experienced as a result of civil wars and the military conflict with Russia.

Whether caused by civil wars, famine, and/or the collapse of basic rural infrastructure, a massive outflow of rural population to the major urban centers would invariably produce “bad” cities plagued by congestion, unemployment and homelessness, crime, prostitution, and drug abuse.

To become more productive, Georgia may indeed have to go through the process of urbanization, but this process should be well managed. Ideally, it should create larger and better cities (in plural!). Cities that offer productive employment and excellent quality of life. For the process to be manageable, however, Georgia has to start investing in rural development, and not Lazika-type adventures.