15

ნოემბერი

2021

15

ნოემბერი

2021

ISET ეკონომისტი

ორშაბათი,

10

დეკემბერი,

2012

ორშაბათი,

10

დეკემბერი,

2012

ორშაბათი,

10

დეკემბერი,

2012

ორშაბათი,

10

დეკემბერი,

2012

Poverty and income inequality are two of the top concerns for the newly elected Georgian government. Indeed, despite impressive growth performance (annual growth rates have averaged more than 6% since 2005), Georgia remains a poor country. Once the wealthiest Soviet republic, Georgia fell far behind others (except, perhaps, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova) on almost any parameter of wellbeing. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, Georgia’s annual income per capita in 2011 was in the $5,400-5,800 ballpark (very similar to the resource-poor Armenia). Moreover, the “median” Georgian, as opposed to the “average” Georgian, is much poorer than suggested by the per capita income estimate. Like any average measure, the income per capita figure masks inequality in the distribution of income, and Georgia is much less equal compared to all ex-Soviet peers (with the possible exception of Russia).

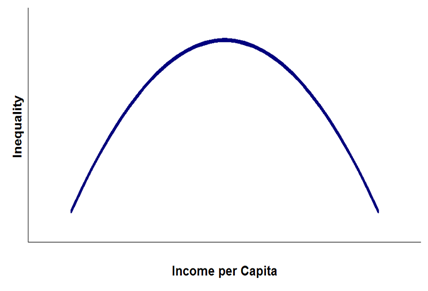

An argument is advanced by some economists that it is perfectly reasonable to expect inequality levels to increase as a country starts to develop from very low levels of productivity, as is presumably the case in Georgia. These arguments find support in a theory that was popularized by Simon Kuznets in the 1950s. Accordingly, market forces tend to bring about higher levels of income inequality at an early stage of development; yet, after a certain level of average income is achieved, inequality would decrease.

The logic behind this inverse U-shaped relationship (“the Kuznets curve”) is based on the British model of modernization and industrialization, as follows:

While logical, this theory has lost its appeal after the 1960s. Not in the least because an entire group of countries constituting the so-called “East Asian Miracle” – Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand – demonstrated the possibility of inclusive growth. In his influential article, “Some Lessons from the East Asian Miracle” (1996), Joseph Stiglitz points out that equality and growth reinforced each other in East Asia: “High rates of growth provided the resources that could be used to promote equality, just as high equality helped sustain the high rates of growth”. In Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, he writes:

“Land reforms were important in the initial stages of development. These had three effects: they increased rural productivity and income and resulted in increased savings; higher income provided the domestic demand that was important in these economies before export markets expanded; and the redistribution of income contributed to political stability, an important factor in creating a good environment for domestic and foreign investment.”

The emphasis on inclusivity was important in later stages of development as well. Higher wages made workers more satisfied, more productive and more willing to cooperate with the firms. Policies that restricted real estate speculation made housing more affordable and helped reduce demands for higher wages. Education policies ensuring universal literacy promoted both greater equity and productivity.

Now, while the East Asian Miracle demonstrates the possibility (and the benefits) of inclusive modernization and industrialization, the main lesson learned from the recent Georgian experience is this: in the 21st century, a developing nation cannot achieve and sustain growth while ignoring concerns for equity. Near universal literacy, access to information, and social networks provide the poor with political mobilization possibilities that were unthinkable in 18th century Britain. Rural development and redistribution policies may come at a significant cost to the economy in the short run, yet they are essential for political stability. Without political stability, no investment, domestic or foreign, will take place.

To summarize, there is nothing “reasonable” or “good” about the wide and persistent income inequality that hit Georgia in the post-independence period. Whatever its virtues, the Kuznets curve hypothesis is utterly irrelevant for any discussion of the Georgian experience. If anything, the Georgian nation became poor and highly unequal because it went through a process of rapid disinvestment and de-industrialization. It was forced to shut down industrial plants, sending scrap metal abroad and workers into subsistence farming or early retirement. Thanks to moderate climate and soil conditions, hunger has never become an issue, yet inequality and associated political pressures rapidly reached catastrophic dimensions, unleashing cycles of violence, undermining the political order and the prospects of economic growth.