30

ივნისი

2022

30

ივნისი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

შაბათი,

22

დეკემბერი,

2012

შაბათი,

22

დეკემბერი,

2012

შაბათი,

22

დეკემბერი,

2012

შაბათი,

22

დეკემბერი,

2012

This blog post is a sequel to “Price of a Woman: Economic Rationale behind Marriage Payments in Georgia”. I recently found very interesting data about bride prices in the Georgian highlands and the North Caucasus, which I am now going to share with you.

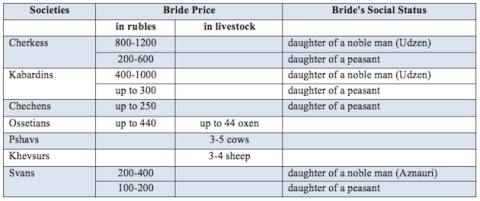

Payment to a bride's parents was widespread in the Georgian highlands and the North Caucasus. This custom was rooted in local traditions and everyone obeyed it. Bride prices were either paid in money or its equivalent in livestock, most commonly in oxen. The price would vary according to the social standing of the bride and personal qualities such as her beauty and age, and whether she was a widow or a single woman. Table 1 below represents data about bride prices in the Caucasus after the Russian Empire’s conquest in the first half of the 19th century.

Table 1. Bride Prices in the Georgian Highlands and the North Caucasus

Prices are given in rubles, the national currency of the Russian Empire at that time, or in livestock. For lack of data, I was not able to convert all prices to the same measurement. I obtained the ox-to-ruble “exchange rate” for Ossetians only but decided not to use this exchange rate to convert other prices.

Differences between the Georgian and the North Caucasus bride price

Bride prices in monogamous societies like those of the Pshavs, Khevsurs, and Svans were mainly determined by the economic value of women and their scarcity. In the Moslem Cherkess, Kabardin, and Chechen societies the custom of polygamy resulted in greater demand for women and higher bride prices.

Ossetians are a complicated case as historically they were Christians, but some of them adopted Islam in the XVII-XVIII centuries. We should thus use caution in interpreting the Ossetian data since we do not know whether it relates to Islamic or Christian families.

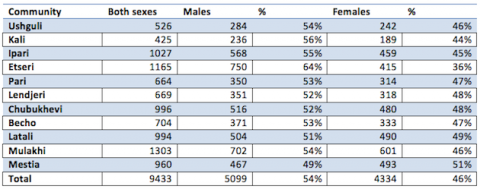

We lack reliable data concerning the three Georgian ethnicities – Svans, Pshavs, or Khevsurs, but my hunch is that bride prices were highest among the Svans. According to available historical accounts, Svanetia has always had the largest disparity between the male and female populations. Table 2 shows the distribution of the Free Svanetia population in 1887 (the earliest date for which data are available).

Table 2: Ratio of males and females in Free Svanetia (adapted from Teptsov V.J., “Svanetia”)

The 1926 census carried out in Khevsureti, another mountainous region of Georgia shows that the total population of the region was 3,472, with females exceeding the male population by about 200 (source: Makalatia S., “Khevsureti”, 1935).

Bride prices among the mountain people of the North Caucasus were strictly regulated by spiritual leaders or at community gatherings. There are several documented examples of such decisions. In 1866, a special meeting was held in the three communities of Northern Ossetia, where the standard bride price (“irad”) was decreased and fixed at 200 rubles. It was also stated that if a groom had no means to pay for his bride, he could pay with labor – being obliged to work for the family of his future wife for eight years! Similar things happened in Chechnya in the mid-19th century where, according to the order of Imam Shamil, the bride price was reduced until it reached the minimum of two cows. In 1879, members of the Ingush republic passed a verdict setting the maximum bride price at 105 rubles. These examples can be viewed as “price ceilings” on brides to ensure that poor grooms had the opportunity to get married. We do not possess similar information on bride price regulation in the Georgian highlands.

As discussed above, in the Georgian highlands, bride prices were lower than on the other side of the Greater Caucasus mountain range. Moreover, they were partially offset by special gifts (called “Satavno”) families gave to their daughters upon marriage. Satavno represented a bride’s personal capital, ensuring her rights in her new family. It is interesting that the sickle (“Namgali”) and scythe (“Celi” or “Satibi”) were two necessary things given as Satavno in the highlands of east Georgia, reflecting expectations concerning the brides’ future role in agricultural production.

About two centuries ago, the bride price custom was quite common ago everywhere in the Caucasus. Since then, however, it practically disappeared in all monogamous societies. In such societies, bride prices reflected economic incentives – they compensated families for the loss of a valuable worker. And they vanished with the weakening of the underlying economic incentives. In polygamous societies, on the other hand, is grounded in religion and culture, this tradition lingers on in the 21st century. Even today, one can find a recommended bride price of 40,000 rubles ($1,300) on the official webpage of the government of the Russian Republic of Ingushetia.

Thus, although I am unable to give a definitive answer to the question I posed in my previous blog post, I have managed to refine my hypothesis: traditions based on a merely economic rationale change or disappear with the change in economic circumstances; traditions that are grounded in religion and corresponding social norms may be better able to defy time and economic rationality.

P.S. For those interested in the peculiarities of the Georgian marriage traditions; in analyzing marriage as a social contract, representative not of a private but a communal affair; in looking at enforcement mechanisms and punishments for breaking such contracts; in comparing male and female socio-economic values, or in any other related issues, I would recommend visiting the National Library of Georgia as many of the invaluable works of the late19th and early 20th centuries are not yet available online.