15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

22

June,

2020

Monday,

22

June,

2020

Monday,

22

June,

2020

Monday,

22

June,

2020

From a trade perspective, the most important aspects of the EU-Georgia Association Agreement, signed on 27 June 2014, including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), are the Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures and the food safety standards and technical regulations required for access to European markets. Georgia’s export to the EU is still rather limited, and one possible cause for this deficiency, amongst others, is the limited capacity to comply with food safety regulations and standards. The DCFTA is, moreover, different from other free trade agreements and implies regulatory approximations, not only for exports but also for domestic trade. Thus, the DCFTA is likely to affect Georgian trade with both the EU and other countries, including members of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC). Consequently, it is important to question how the DCFTA has affected the top Georgian trade commodities with CAREC countries.

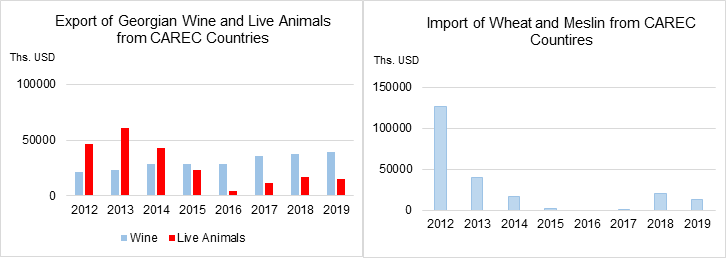

CAREC unites 11 countries (Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, the People's Republic of China, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), the fellow members of which are important trading partners for Georgia. By volume of export and import, Georgia’s major CAREC trade partners are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and the People’s Republic of China. While, the chief export-import agricultural commodities are wine, live animals, and wheat; wine and live animals are the top export products, and represent a significant source of income, whereas wheat is a top import.

Graph 1. Trade with CAREC countries

Georgia imports over 80% of the wheat it consumes (Geostat, 2019). In 2019, from the total imported wheat and meslin, 88% came from Russia and 10% from Kazakhstan. Interestingly, compared to 2012, by 2019 wheat imports from CAREC countries had decreased by 90%, this was largely because Georgia moved to the Russian market, which it now depends on heavily.

As for the trade restrictions, there are no restrictive norms in Georgian legislation to hinder trade from Kazakhstan or Russia. There are also no technical regulations on wheat in place to set the standards for the quality of imported wheat or for the conditions of transportation. This absence of regulations, therefore, encourages importers to purchase low-quality wheat. Wheat producers highlight that the procedures monitoring the quality of imported wheat differ according to the means of transportation. Documentation, ensuring the safety and quality of wheat, is only required for shipping and rail delivery, however, for motor vehicles, there is no comprehensive list of necessary customs documentation, and the requirements often change. Consequently, Georgian wheat producers are attempting to implement certain Technical Regulations on Wheat. These regulations will control the quality of both imported and locally produced wheat.

Turning to the export of live animals, Azerbaijan is a top destination country, constituting 38% of total export. Meat production in Georgia is controlled by a technical regulation that defines veterinary and sanitary rules. There is also a technical regulation for the labeling of meat and meat products. However, none of these regulations apply to live animals. Ultimately, there are no SPS regulations to hinder the export of live animals, and exported products only need to comply with the regulatory framework of a destination. Thus, exports need only satisfy the specific requirements and standards, if any, requested by a buyer. For instance, buyers from Azerbaijan have no restrictions that may affect trade, and live animals easily satisfy Azerbaijani regulations. However, it should be noted that since January 2019, the export of live animals weighing less than 140 kg has been prohibited. This regulation became yet more strict in February 2020, when the minimum weight requirement increased to 200 kg.

Another top export commodity is wine. Nevertheless, the market is rather concentrated. In 2019, Russia accounted for 60% of total export, followed by Ukraine (10%), and the People's Republic of China (8%).

Wine is subject to stricter sanitary, phytosanitary, and quality-related regulations than wheat and live animals, enabling the construction of a four-part stringency index: quality standards; phytosanitary; labeling, marketing, and packing requirements; and border quarantine measures. These indices are used to address the effect that Sanitary, Phytosanitary and Quality (SPSQ) measures, and standards have had on the export of wine. The results reveal that:

• The higher the average perceived stringency of the SPSQ standards/regulations, the fewer wine exports occur in a particular year. Although these effects are insignificant, and the result is as expected. Stringency has a negative effect on the wine trade, indicating the further need for trade development, strong assistance to wine exporters, and improved end-product quality;

• The labeling, marketing, and packing requirements are the most problematic to deal with and the most restrictive for trade;

• Georgia’s wine exports are lower for high-income countries, indicating that, currently, the county sells relatively cheap wine, and targets low-income consumers, indicating the need for greater promotion in high-end markets.

There are, at this stage, no SPSQ regulations limiting the trade of wheat or live animals. However, an upcoming regulation on wheat might tighten, and improve the quality of, the imported product, and hinder unregulated trade. While currently only one restriction is imposed on the export of live animals (those under 200 kg), beyond which, there are no SPSQ regulations deterring the trade. Regarding wine, the perceived stringency has increased for all four SPSQ-related regulations for the trade; this may be due to the effect of the newly introduced, more restrictive, regulations related to Georgia’s commitments to the DCFTA. Nonetheless, Georgian exporters consider all four regulations to be quite restrictive.

In order to reduce the possible negative effects of the regulations on Georgia’s agricultural trade flow with CAREC countries, governmental agencies and sectorial associations should:

• Invest in facilities to harmonize SPSQ measures within the CAREC region and at borders;

• Tailor policies in order to help producers develop capacities that comply with the requirements;

• Engage in regional and international cooperation and policy dialogues;

• Develop and enhance the technical skills of personnel engaged in SPSQ-related areas.

To improve market connectivity and agricultural value chain linkages within the CAREC region, interactions between the private and public sectors should be increased. CAREC countries should also connect the regional agenda with local issues and establish Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) for regional integration initiatives, which would provide greater predictability and institutional stability throughout the region.

This study was conducted by ISET Policy Institute under the CAREC Think Tanks Network (CTTN).