15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

06

April,

2015

Monday,

06

April,

2015

The Estonian-Georgian film, Tangerines, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2014. While the film was shot in Guria, the story takes place in Georgia’s breakaway region of Abkhazia during the war in the early 1990s.

In the film, two of the main characters are peasants from Estonia who are living and working in Abkhazia, one as a tangerine grower and the other as a manufacturer of wooden crates for transporting tangerines to markets (much like the one in the photo above). Unlike their families and neighbors, these two men did not leave the region during the war for a variety of reasons, including their ambition to harvest and market their tangerines.

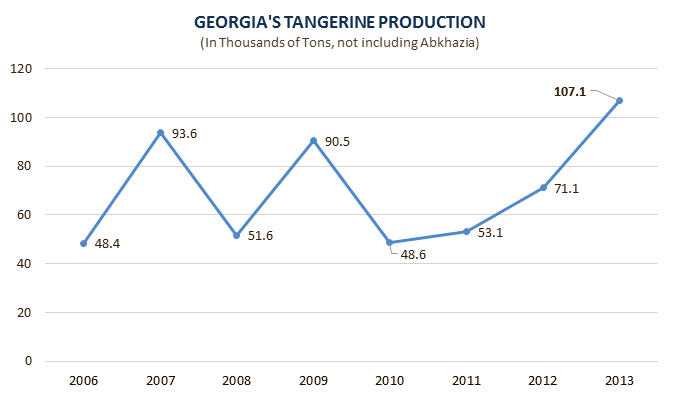

Tangerines are the main citrus fruit produced in Georgia, mostly grown in western Georgia (in Achara, Guria, and the breakaway region of Abkhazia and to some extent in Samegrelo and Imereti). While tangerine production has fluctuated from year to year, nearly 107,000 tons of the fruit were harvested in 2013.

Many peasants from western Georgia are dependent on tangerine production for their families’ livelihoods. When I was a child, many farmers from Achara were coming to my home village, Kvemo Alvani, in Kakheti (which is nearly 500 km away from Achara) to sell their tangerines for cash or exchange them for other agricultural products (potatoes, corn, or wheat, for instance). Tangerine growers used to informally cooperate by renting a bus and selling their tangerines together. Such cooperative practices persist to date, though local traders also play a critical role in market intermediation.

The main export markets for Georgian tangerines are currently Ukraine and Russia, as illustrated by the graph. Unfortunately, Georgian tangerines are not (yet) competitive in the more lucrative European markets, primarily due to limited advances in the quality of tangerine harvests and in post-harvest treatment.

Tangerines are typically grown and harvested by a very large number of small family farmers. Given its political significance, this sub-sector has often been the subject of government subsidies and other policy interventions.

In 2013, the government started to subsidize the sector. A 10 tetri subsidy per kilogram of “non-standard” tangerines (those which may be slightly damaged or misshapen) was provided to farmers for tangerines delivered to processing companies. Farmers received an additional 15 tetri per kilogram for standard tangerines which were exported. In total, the government spent 13.8 million GEL from its reserve fund, with about 12 million GEL spent on subsidies for standard mandarin production and another 1.8 million GEL on subsidies for non-standard tangerines.

Due to unfavorable weather conditions, a substantial part of the 2013 harvest consisted of non-standard tangerines. To account for that, the subsidy scheme was applied in a slightly modified form in 2014. Companies had to purchase non-standard tangerines for not less than 20 tetri per kilogram. If they did so, they received 10 tetri per kilogram in government subsidies. A total of 2 million GEL was allocated to this program. The government also opened a coordination office and started a hotline in Achara to try to improve the marketing and processing of both standard and non-standard tangerines. The latter was purchased and processed by three fruit plants in Achara, including one financed by the government’s preferential credit program.

Last year, the government also launched a heavily subsidized agricultural insurance pilot program. This year, due to three hailstorms, much of the tangerine crop was damaged, resulting in payments to farmers by insurance companies amounting to nearly 1.8 million GEL.

Arguably, many of these initiatives are aimed at supporting growers and processors in the short run. These policies do not necessarily provide incentives for Georgian tangerine farmers to improve the quality of their products or to try to enter premium markets for tangerines or juices. Thus, it might be more efficient for the government to target the skills and technology bottlenecks for improved production, harvesting, and post-harvest treatment.

For instance, the now completed Economic Prosperity Initiative (EPI), a USAID-financed program, was undertaken with both of these aims in mind. Agricultural experts from California were invited to Georgia to share their experiences and train farmers on the proper treatment of their tangerine trees with regard to trimming, land cultivation, application of fertilizers, and harvesting. According to an article in Commersant (available in Georgian), as a result of these trainings, some farmers adopted new technologies and had better harvests, which varied from 55 kg to 100 kg per tree. This is less than the Californian norm of 200 kg per tree but much better than the current average of only 35 kg. Furthermore, the quality of the tangerines was higher: they were larger in size, had more uniform surfaces, and improved color.

A separate set of measures could be undertaken to improve the manner in which tangerines are sorted, stored, transported, and processed. Such measures might include taking the form of supporting the establishment of growers’ marketing cooperatives or even export-oriented collection centers. The government could also coordinate the actions of private sector players aiming at identifying and entering new export markets, which is rather important considering recent events in Ukraine and Russia.

At the same time, one has to remember that any policy initiative has its costs. As stated in a recent UNDP/ENPARD report on agriculture in Achara, “unlike mandarins, money does not grow on trees: in order to subsidize agriculture, the government has to tax the rest of the economy.” Which of these initiatives are most cost-effective in the long run or whether or not any of them should be at all undertaken remain open questions.

Last year, Georgia signed the Association Agreement with the European Union, which will enable Georgian farmers to sell their products in European markets if they meet the standards set by the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA).

One EPI/USAID expert believes that if Georgian tangerine farmers adopt new technologies and strictly follow the lessons from their trainings, Georgian tangerine plantations could be producing crops suitable for European markets in about five years. This would enable growers to receive higher prices for their tangerines and therefore improve a lot of their families.

Better access to markets could also lead to political benefits. If farmers in Abkhazia are willing to imitate growers in Achara or Guria and undertake similar improvements in their production and marketing practices, they might be able to achieve access to European markets as well. This could contribute to higher prices for producers, on the one hand, and greater trade and a thawing of relations between Abkhazia and Georgia, on the other. Such trade and improved relations would hopefully prevent another Citrus War, as described by the two Estonians in the film, from happening any time in the future.

* * *

The article was produced with the assistance of the European Union through its European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus.