15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

07

May,

2018

Monday,

07

May,

2018

Monday,

07

May,

2018

Monday,

07

May,

2018

Since 2012, when the political party Georgian Dream took leadership of the country’s governance, economic [real] growth reached its highest rate in 2017 (5.0%). The drivers of this growth were construction (11.2%), hotels and restaurants (11.2%), and the financial sector (9.2%). However, a few sectors of the economy declined in 2017, and one was agriculture (-2.7%).

Experts on this sector agree that 2017 was a “bad year” for Georgia’s agriculture. Winter lasted longer and spring frost damaged fruit plantations. This was followed by some periods of drought, as well as heavy rains in some regions of Georgia. In addition, the stink bug epidemic spread in western Georgia and damaged the harvest of many products, especially the country’s one of the main “cash crops”, hazelnut. Furthermore, some experts question the data on agricultural employment in the country. While the official data shows a persistent trend of around half of the Georgian labor force being employed in agriculture, such figures tell us little about the real story (e.g., there is no data on hours actually worked in agriculture). Perhaps (and hopefully), some workers have almost left agriculture, and thus, without technological progress, it is not surprising that less output is produced in this sector. All of these arguments might be true, but it is difficult to judge whether or how much each of these factors contributed to the decline of agriculture in 2017.

According to Geostat’s preliminary data for 2017, the decline touched almost and every sub-sector of agriculture. Compared to average numbers between 2014 and 2016, sown areas declined by 17% in 2017, and so did the production of top annual crops – wheat (-7%), maize (-39%), potatoes (-19%), and vegetables (-19%). The only crops with increased production in 2017 (compared to the average of 2014-2016) were barley (+12%), oats (+4%), and pepper (+9%) (see more on sown areas and production in April’s Agri Review).

As for permanent crops, all three big categories have experienced a decline in 2017, compared to the average production of 2014-2016: fruits (-38%), grapes (-9%), and citrus (-19%). Only a few types of fruit production increased in 2017, compared to the average of 2014-2016, and among those were peaches (+18%) and berries (+73%).

Livestock products followed the trend as well. Compared to the average of 2014-2016, the following changes were observed for the production of livestock products in 2017 – meat (-10%) and milk (-11%); eggs stayed almost unchanged.

Some positive changes were also observed in 2017. The productivity of some agricultural goods increased, for example: barley (+12%), oats (+33%), beans (+11%), and vegetables (+2%). However, one should not judge agriculture only by one year. In previous years, some farms were surely becoming modernized and developing along the value chain, but this does not change the big picture. A lot still needs to be done to improve agricultural productivity in the country.

Not only agricultural output, but also the share of agriculture in the country’s GDP, has declined from 9.1% as the average of 2014-2016, to 8.2% in 2017, which itself is the lowest number ever recorded (Geostat, 2018). The low share of agriculture in overall GDP is not a problem as such; the world average was 6% in 2015. This number is even lower for developed countries; it varies between 1% and 3%. So, the observed decline would be welcome for Georgia’s economy, if not for the fact that more than 40% of the labor force is “employed” in agriculture. The same indicator is much lower in the developed world and does not exceed 5%.

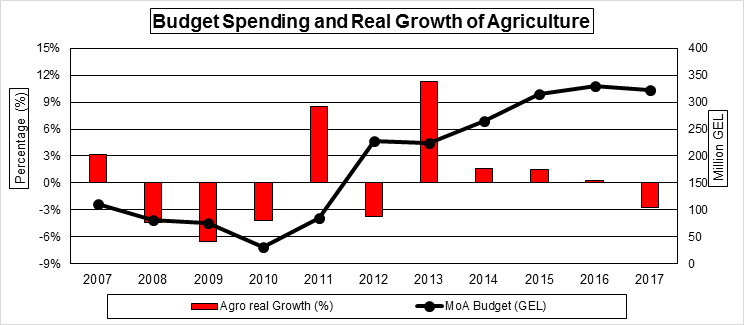

S0, the contribution of this 40% of the workforce to the country’s GDP is very modest, because the productivity of the sector is still very low. This, as well as recognition of the role of increased agricultural productivity in poverty reduction (this role is much debated, though), has placed the agricultural sector high on Georgia’s policy agenda. Since announcing agriculture as a priority sector in 2012, huge efforts have been devoted to revitalizing this traditional sector of the economy. In particular, government spending increased from nearly 1% to more than 3% of the total budget, including many new projects and programs with direct and indirect subsidies.

Despite the increase in government spending and much more support from the international community and private sector, the sector’s real growth was modest during 2014-2016 and became negative in 2017 (see graph above). Many experts now question the effectiveness of such spending and argue about the necessity of better targeting and the gradual decrease of support to the sector. But should Georgia consider a decrease in the support of agriculture? Or is it perhaps better to decrease some kinds of support (e.g., direct subsidies to farmers, as when the Georgian government decided to phase out an input voucher program in 2017) and increase others? While an assessment of the effectiveness of different programs would help, data and lack of resources limit the availability of the thorough analyses needed to answer these important questions.

Agriculture is one the most supported economic sectors in the world, especially in the European Union (21% of gross farm income) and the USA (9%) (OECD, 2016). There are many ways of supporting this sector, through both direct (vouchers, grants, subsidizing prices, etc.) and indirect subsidies (subsidizing the interest rate and agro insurance premium, etc.). However, agricultural support is generally decreasing in OECD countries (from 33% in 2000 to 19% in 2016). While farmers in most developed countries are well organized and can engage in serious lobbying, there are still some examples of sharply reduced support. Those examples demonstrate the importance of implementing a good exit strategy from subsidies in order to make the sector healthier because it is well known that wherever subsidies are involved, many farmers are farming solely for those subsidies.

One example of a successful case of withdrawal of subsidies in New Zealand. The sudden and unexpected removal of subsidies took place back in 1984, which “has given birth to a vibrant, diversified and growing rural economy,” according to a report made by the Federated Farmers of New Zealand published in 2005, more than 20 years after the removal of subsidies. Productivity has improved and growth in agriculture has outpaced the growth of the New Zealand economy as a whole.

While the first few years after subsidies were hard, it helped farmers to become more professional, innovative, and business-oriented. Some farmers diversified their income portfolio and started to practice agro-tourism activities at their farms.

After removing subsidies, the New Zealand government provided advice to farmers on whether they should leave the agriculture sector or stay in this business, and also provided farmers with one-time “exit grants”. Today, the New Zealand government mainly provides agricultural research funding, but all other subsidies have been removed (e.g. production grants, fertilizer subsidies, taxation schemes, and concession loans). The positive results of the farm subsidy reforms are visible in rapid technological improvements and increased land and agricultural labor productivity in the country (Lattimore, 2006).

“What’s happened since the reforms is that you have a new type of farm emerging – a business farm,” Malcolm Lumsden, a dairy farmer from New Zealand, told the New York Times. Yes, farming requires first the business approach!

One sub-sector of Georgia’s agriculture sector flourished last year, and it was the wine industry. The brand name of “cradle of wine” paid off for the country, and the value of wine export ended the hazelnut’s almost a decade “hegemony”, and again topped food and agricultural exports from Georgia (170 million USD value of wine was exported in 2017). It is worth mentioning that 2017 was the year when the government started exiting from direct subsidies for grape prices; only 19 million GEL was expended, compared to 36 million in 2016. A similar subsidy budget is planned for 2018…

The wine industry is not only the leading agricultural sector of Georgia, but it is also the “successful case” compared to other sub-sectors of agriculture. Of course, the sector still faces many challenges (dependence on CIS markets, decreasing prices of exports, etc.), but it is the most advanced agricultural sector in the country. Having said that, if the government would like to continue its exit strategy, when removing direct subsidies for wine (price subsidies), the government should invest more in monitoring wine quality, invest in branding, marketing, and support for small and medium winegrowers and cellars to help them develop value chains and have direct access consumers, or at least to foreign intermediaries. By doing so, efforts should be directed to the export markets outside of Russia and former CIS countries, to decrease the dependence on traditional markets, which are risky because of well-known facts experienced in the past (see our previous blog).

Overall, it is clear that the New Zealand case would be difficult to implement in Georgian reality. Some types of support, such as subsidizing loans or insurance premiums, deal with systemic problems to be overcome (see this or this on those topics). Nevertheless, better targeting and clear exit strategies should be considered, not only for grape price support but also for other types of subsidies. Of course, this does not mean that spending in agriculture should be sharply reduced in Georgia; on the contrary, different programs should be analyzed in detail to learn more from these pilots and use the insights for better planning. And perhaps one day Georgia will be ripe enough to follow New Zealand’s example.