15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

26

September,

2015

Saturday,

26

September,

2015

Saturday,

26

September,

2015

Saturday,

26

September,

2015

On August 20, 2015, a strong hailstorm hit Georgia, devastating crops and infrastructure in eastern Kakheti. In Kvareli alone, the hailstorm destroyed about 1,300ha of Saperavi and 1,000ha of Rkatsiteli grapes, affecting more than 500 families. This was only one in a string of natural disasters striking Georgian farmers in recent years. One of the worst calamities occurred in July 2012, when heavy rain, strong winds, hail, and floods damaged thousands of hectares of arable land in Kakheti, ripping roofs and destroying vital infrastructure.

While natural disasters cannot be prevented, farmers can use technological solutions, such as hail nets or irrigation, to minimize crop losses. Not to put all eggs in one basket, they may choose to hedge against localized weather-related losses by diversifying crops and growing locations. While coming at a cost, such risk mitigation measures would help reduce income variability. Finally, crop insurance could be used as a complementary risk-mitigation tool in case of extreme weather events such as early freezes, floods, droughts, and hurricanes.

Yet, until 2014, agricultural insurance was almost unheard of in Georgia. Instead of buying insurance, the vast majority of Georgian farmers preferred to play Russian roulette with Mother Nature. They did so being chronically short on liquidity, underestimating risks, and … counting on a government bailout.

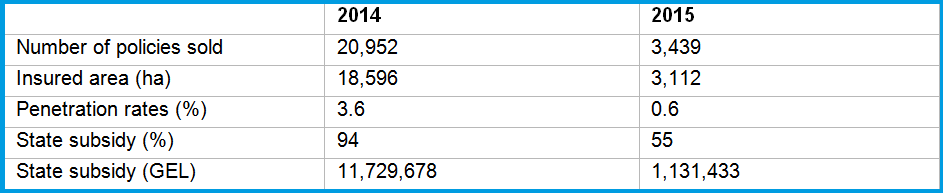

In 2014, the Georgian government started piloting a heavily subsidized crop insurance scheme in the hope of shifting the market to a new “equilibrium”. Almost 21,000 policies were “sold” in that year at a symbolic price equal to about 6% of the actual cost (the government covered the remaining 94%, on average). Yet, one year later the number of policies sold plummeted to less than 3,500, as soon as the government reduced the amount of subsidy to 55% (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Agricultural Insurance Pilots, 2014 vs. 2015

There were also other reasons for the dramatic drop in the number of policies sold in 2015. Not only was the subsidy reduced from 94 to 55%, but also it was made available only to smallholders (this also explains the even larger drop in the amount of land insured). And, of course, some more insurance policies may be sold until the end of 2015. Nevertheless, it is already clear that the pilot has failed to produce sustainable results.

Two questions must be asked: why more than 10mln GEL in taxpayers’ money spent on subsidies failed to jump-start the agricultural insurance market? And, can the Georgian government do any better?

In their 2011 bestseller Poor Economics, two MIT professors Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee argue that managing a poor rural household is akin to the responsibility of running a hedge fund, yet doing so in the absence of modern risk mitigation instruments, such as insurance, options, futures, etc. Moreover, while hedge fund managers (or people in the middle of the income ladder) can afford small negative income shocks, for poor households even a small drop in income would require cuts in basic food, housing, health, and education expenditures.

According to Duflo and Banerjee, to manage risk, the poor engage in primitive hedging strategies that prevent them from specializing and achieving productivity gains. Examples of such strategies are: mutual help within extended families, plot and crop diversification (thus forfeiting any gains from economies of scale in production), and abstention from costly investment in (risky) innovations such as higher yield hybrid seeds. While essential in the presence of severe downside risks (e.g. related to weather events), these strategies are costly and keep the farmers entrapped in poverty.

Agricultural insurance could relieve poor farmers from the need to engage in primitive hedging and in this way help them to specialize in more productive activities. This being the case, the poor could be expected to flock to agricultural insurance, whenever available. Yet, as Banerjee and Duflo point out, the opposite is true. According to Robert Townsend and coauthors, when given the opportunity, only 5 to 10% of low-income Indian farmers insure themselves against drought, even though they identify precipitation as a major source of risk. According to Dean Karlan, farmers are often not willing to purchase insurance even when its price is close to zero and much lower than the actuarially fair price. The natural question to ask is why there is such a low demand for insurance among poor farmers?

Banerjee and Duflo identify several factors. The first among these is what the authors call a “demand-wallah” argument, which very well applies to the Georgian situation. When hit by hailstorms and winds in July 2012 (just three months before the fateful parliamentary elections), Kakhetian farmers received around GEL 150 million in compensation, including GEL50 million in government funds and another GEL100 million from ex-Prime Minister Ivanishvili’s foundation. In other words, Kakhetian farmers may have been playing Russian Roulette with natural disasters, yet they did so with a gun loaded with blanks!

Agricultural insurance is not a cheap proposition in Georgia. At the going rates, a Georgian hazelnut grower owning 1.5ha would be asked to pay an insurance premium equal to 2.4% of his/her income, if subsidized by the government, and 6.1%, if not. It is, therefore, not surprising that given an implicit bailout guarantee by the Georgian government, farmers have no strong incentives to purchase insurance, and, even more detrimentally, mitigate risk in their farming practices. On the other side of the coin, given the meager size of the agricultural insurance pie, insurance providers have little incentive to invest in research and data analysis or come up with innovative products that are a better fit for the Georgian market.

There are, of course, many factors standing in the way of an orderly insurance market. For example, farmers may not trust insurance providers and lack a proper understanding of the insurance concept. Moreover, they may be reluctant to commit their scarce resources given their experience in dealing with unskilled sales agents and loss adjusters. But, above everything else, the Georgian government’s efforts to roll out agricultural insurance have thus far been undermined by its own (implicit) commitment to bail out uninsured farmers. Certainly in an election year!

Despite their general unwillingness to purchase insurance, farmers might be nudged towards insuring themselves with the help of simple behavioral “tricks”. For example, in an experiment conducted in the Philippines, randomly selected participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire about their health status. When subsequently offered health insurance, those who answered the survey, were significantly more likely to buy insurance.

Farmer cooperatives may also be an important instrument of nudging farmers to insure against risks. Miles Kimball was the first in 1988 to acknowledge and model farmers’ cooperatives as a self-enforcing body able to provide insurance to its members. In Georgia, the first steps have been already taken towards this end by the Georgian government and the EU’s ENPARD initiative. However, more can be done.

In particular, as has been shown by Karlan et al (2013), the best results could be achieved by combining grant incentives with the requirement to acquire insurance. While true in the case of individual farmers, the same policy could be particularly effective in the case of farmer cooperatives seeking to specialize and innovate in a competitive market environment. At present, the vast majority of ENPARD-supported cooperatives are not insured. By providing relevant training and grant incentives, ENPARD could complement the Georgian government’s efforts to prevent the hollow Russian Roulette practice from stifling development in Georgian agriculture

* * *

The article was produced with the assistance of the European Union through its European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus.