15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

20

November,

2017

Monday,

20

November,

2017

Monday,

20

November,

2017

Monday,

20

November,

2017

Nikoloz M., 65, from the Imeretian village of Jikhaishi, invested around 15,000 GEL into his 8.5 ha hazelnut orchard in 2012, hoping that one day his initiative would turn into a profitable business. Nikoloz was on his way to success up until this year, before the stink bug, or Asian pharosana, as Georgians call it, appeared in his orchard. While Nikoloz expected to harvest 800 kg – 1000 kg of hazelnuts per ha, the stink bug infestation reduced his harvest by 30-35%, resulting in a loss of more than 1,000 GEL per ha. For a rural household with average annual earnings of 11,000 GEL, losing up to 9,000 GEL is a big deal.

Yet Nikoloz’s case is not the worst; in West Georgia, pharosana invaded not only hazelnuts, but other crops as well. Farms in the Abkhazia region saw the biggest damage.

“In addition to causing severe damage to hazelnut trees, pharosana destroyed all the fruit trees, particularly tangerines and feijoa. It damaged maize as well,” – said Marina K, 67, village Repi, Abkhazia region.

A similar situation was described by a native of the Gurian village Chanieti, Irakli L, 65, who expected to get 500 kg from his 0.2 ha hazelnut orchard, but got only 60 kg. “The hazelnut kernels were either rotten or empty, and if at the collection point 5 kernels out of 15 randomly picked hazelnuts were good, then you would get 0.50 GEL/kg. You were basically getting 0.10 GEL per each good kernel. Thus, if only 3 out of 10 were good, you would end up with 0.30 GEL/kg, which is an extremely low price.” There were even cases when collectors refused to receive the harvest, suspecting low quality, or farmers did not agree to sell hazelnut for such a low price.

Pharosana is native to East Asia. It is an agricultural pest which attacks fruit trees and vegetables, damaging the surface and leaves of the crop. The insect becomes active in late spring (late May – beginning of June) and attacks crops till the middle of fall. Once the weather becomes colder, the pest moves to houses and structures which become its shelter during the winter. Pharosana reproduce very fast, resulting in big populations within the short period of time.

|

Asian pharosana firstly appeared in Georgia in 2015, and by now has severely damaged crops in West Georgia. The Government has already undertaken some measures to fight the pest, however, most farmers are concerned with timeliness and the effectiveness of those measures.

In order to increase the population’s awareness about the threats posed by pharosana, the National Food Agency (NFA) of Georgia divided the crops prevalent in Georgia into three categories based on their exposure to pharosana (Figure 1). Unfortunately, grapes and hazelnuts – the most important agricultural export commodities of the country – ended up in the riskiest group. Hazelnut producers have already experienced significant losses, and if during this winter effective fighting measures are not identified, the pest might spread to the rest of the country, threatening yet another cash crop of Georgia – grapes.

According to the hazelnut producers, the current year was not the best year for hazelnuts, which suffered from various fungal diseases due to unfavorable weather conditions. The pharosana invasion worsened the situation, and in the end, hazelnut exports dropped dramatically in both value and quantity.

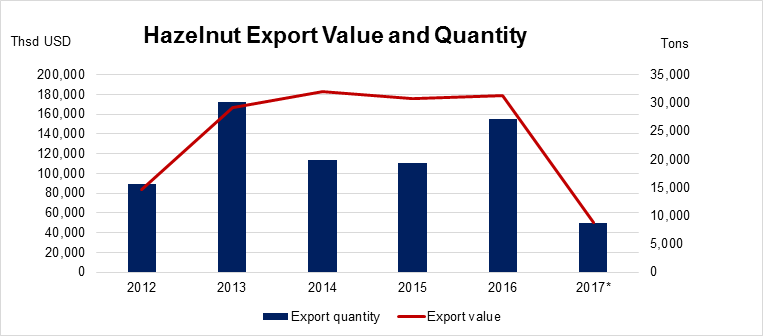

Figure 2. Hazelnut export statistics

The current year is not yet over, however, it is clear that the figures for 2017 are extremely low compared to previous years. From January to September 2017, Georgia exported 50 mln. USD worth of hazelnuts, whereas in 2016, the export value for the respective period was 116 mln. USD, resulting in a 57% drop in export values. While the pharosana is not the only cause of this drop, it played an extremely large role in the reduction of hazelnut exports in both physical and monetary terms.

Pharosana emerged as a very damaging invasive insect in North America and Europe in the mid-1990s and 2000s. The first established population of pharosana in Europe was identified in Switzerland in 2007. As to other European countries, there are established BMSB populations in Italy, France, Greece, Hungary, Serbia, and Romania. Bulgaria and Russia joined the list of countries with high number of sting bugs just recently.

In the US, where the pharosana was accidentally introduced in 1998, it has been detected in 40 states, causing relatively serious agricultural problems in six states, and nuisance problems in thirteen others. Pharosana has already resulted in a significant damage to agricultural crops and associated unpleasant economic impacts to growers in 2010, during an outbreak that led to a one-year loss in excess of $37 million across the mid-Atlantic in apples alone, as well as 100% losses to peaches in Maryland, and 60-90% losses of peaches in New Jersey. Pharosana continues to damage sweet corn, pepper, tomato, eggplant and okra plots in the US.

Managing pharosana populations is challenging because there are currently few effective pesticides that are labeled for use against them. Researchers are looking into ways to effectively control pharosana populations, but more experiments need to be conducted in order to identify the most effective measures.

Using insecticides is the most common measure applied against pharosana in Georgia and all over the world. However, recent research has shown that pharosana become resistant to some of the common insecticides. This fact has led to trials of new insecticides such as Oxamyl which resulted in 96% mortality rates during field trials.

Yet another measure is to use the chemical compound kaolinite (Kaolin clay) for apples. This chemical is considered to be the most efficient method to protect apples from pharosana. Unfortunately, kaolinite is only effective on apples and does not protect other crops.

Researchers emphasize the importance of discovering so-called native biological enemies of the pharosana, and have concluded that Trissolcus japonicas – a parasitoid wasp also known as “samurai wasp” - is a primary predator for the pharosana. Trissolcus japonicus searched for and destroyed 60–90% of BMSB eggs in Asia, which is definitely a promising result. However, if a biological enemy is introduced in Georgia (and in any other non-native country), there is a risk that the newly introduced insect will become an invasive pest and cause problems similar to those caused by pharosana. That is why researchers prefer to first identify biological enemies native to the country, and introduce something new only if there is no other alternative. Native predators such as wasps and birds can serve as a viable tool for fighting pharosana.

In Georgia so far, the Government has subsidized the use of insecticides and is considering the introduction of a biological enemy in order to ensure that next summer does not turn into yet another pharosana nightmare for Georgian farmers.

* * *

This article has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) and Austrian Development Cooperation, in partnership with CARE. Its content is the sole responsibility of ISET-PI and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, and CARE.