31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

03

May,

2019

Friday,

03

May,

2019

Friday,

03

May,

2019

Friday,

03

May,

2019

News of the conflicts between the local population and the construction company involved in the construction of a small HPP in the Pankisi valley (Khadori 3) has recently made it into the headlines. Khadori is a small HPP with an installed capacity of 5.4 MW and an estimated annual generation of 27.5 mln. kWh. Construction of the Khadori 3 HPP started on 21 April, however, the local population resisted the project, and consequently, its company involved law enforcement officials to ensure its secure implementation. This further increased tensions between the government and the local population, which resulted in conflict.

The conflict was apparently based on the diverging expectations of the environmental and health impacts of the small HPP’s construction and operation. Considering the echoing intensity of the local population’s response, we decided to learn more about the project, and to treat it as a case study, to analyze the possible constraints of building small HPPs in Georgia.

The Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) report for the Khadori 3 HPP has been publicly available on the ministry of environment and agriculture’s official website since 2017. It is designed around the old Georgian Law on Environmental Impact Permits, abolished in 2017, as the project was approved before these legislative amendments.

The elaboration of an environmental impact assessment before the construction or operation of any HPP is a compulsory procedure in many countries, including Georgia. The main goal of an EIA is to evaluate a project’s implementation, which includes assessing the existing technical documentation of planned activities and information regarding the natural and social environment. The determination of the expected environmental and social impacts (including residual and cumulative) on different phases of a project should be obtained when analyzing and appraising the relevant information. The most important facets of an EIA are the identification of any mitigation measures (necessary to identify negative impacts), the establishment of environmental management and monitoring schemes, and ensuring public awareness about planned activities and engagement.

An EIA is a comprehensive document, analyzing several types of project impacts. As economists, we opted to investigate the sub-chapters of the Khadori EIA, which describe both the socio-economic conditions in the area and the socio-economic impacts of the project.

We discerned that reviewing the socio-economic conditions detailed within the sub-chapter does not offer a truly precise understanding of the conditions, as the data provided refers either to the municipality or to the region, and not to the area most directly affected by the project. This poses an important question: how does one define a project implementation area? Is it a whole municipality, a region, or those settlements that are the most subject to the direct social, economic, and environmental impacts of its implementation? We believe the last option offers the best definition for small projects, like the Khadori HPP. When considering the sub-chapter on the possible socio-economic impacts of implementation, we found that it includes a quite simple methodology, which only distinguishes the impacts according to a “sign” (positive or negative) and an “intensity” level (low, medium, or high). Although the range of impacts analyzed is quite exhaustive (among them: the impact on resource usage, employment, transportation infrastructure, health, and risks of environmental damage and on the economic benefits), the information provided, once again, lacks detail.

The document offers a vague, description of each impact and provides unsubstantiated quantitative results. It delivers neither detailed information on any specific methodology, the approach used to assess the impacts, nor a proper reference to any previous studies or to the qualitative data utilized to support the conclusion of their analysis. Subsequently, one cannot check the validity of the underlying assumptions, conclusions, or rationale behind the approval of the project in terms of economic profitability. One can only safely assume that the project is financially viable for its investors, however, this is not enough to conclude whether the project imposes the relevant economic costs on third parties (such as the local population).

For impartiality, it is important to mention two further significant aspects: (i) the report on the ecological expertise of this particular EIA does not highlight any problems with the sub-chapters covering the socio-economic conditions and impacts of the projects. It simply touches on the environmental impacts of the project, and it requires that the project implementation team provide additional documentation to the ministry. (ii) The comprehensive data of settlements’ socio-economic conditions are not collected in Georgia. The main socio-economic indicators, such as unemployment, business activity, etc., are statistically representative only at the regional, or municipal, level at best. Thus, any significant research trying to assess expected socio-economic impacts would have to conduct separate data collection within the project implementation area to identify these necessary indicators. It, therefore, appears that a tradeoff exists between conducting a cheaper socio-economic investigation of the project, performed with inadequate detail (and mainly for ticking boxes), and a more accurate, but relatively more costly, analysis. Clearly, if the socio-economic analysis is not expected to be thoroughly scrutinized, there is no incentive to undertake a more costly process.

We believe, as one of the major goals of the EIA is to provide clarity and transparency in the implementation of projects that have potentially negative impacts on third parties, that the quality and the level of detail of the socio-economic assessment and environmental impacts within the EIA should be improved upon. This would facilitate a dialogue between the investors and communities involved, as well as the adoption of adequate risk-mitigation measures, thus helping diffuse tensions and prevent clashes like those at Pankisi.

On a positive note, the assessments of the environmental and social impacts of all projects in Georgia are, currently, regulated by a new (improved) law. The law states that communities should be involved in the environmental impact evaluation process, at the earliest stage possible, in order to consider the opinions of all stakeholders. Nevertheless, without accurate data and greater scrutiny, even the improved legislation may fail to avoid certain misunderstandings and the provocation of unnecessary tensions among different parties.

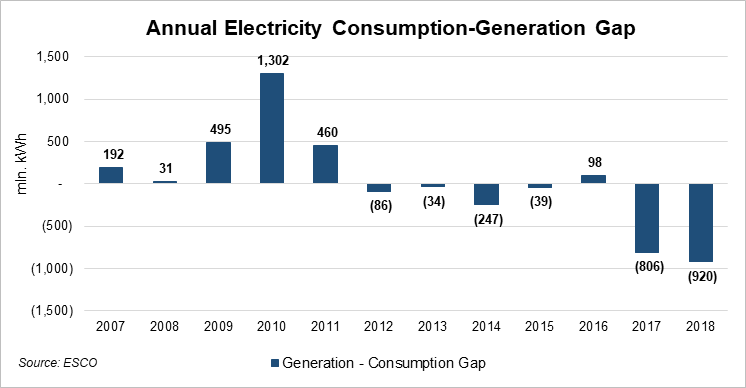

Although one HPP produces 27.5 mln. kWh per annum may not make a notable difference in the power sector, it is evident that small HPPs in Georgia could help cover part of the widening negative gap between generation and consumption. This gap now typifies most of the year, with the exception of the summer,1, and has been intensifying over the past two years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual Electricity Consumption-Generation Gap (Deficit) including transmission losses

This deficit may well become more severe still unless more proactive measures are taken. One of such measures is the popularization and acceleration of investments in renewable sources, including small HPPs, which, relatively, have a smaller negative impact on the environment. Otherwise, any political or market instabilities, connected to the main energy suppliers, Russia and Azerbaijan, may cause potential power outages, which can have significant economic and social costs. For example, Michael Schmidthaler and Johannes Reichl estimated that a power outage in Italy on 28 September 2003 caused over 1.15 billion Euro of damage to society,2 which corresponds to almost 0.1 percent of the annual Italian GDP. In a study of the Pakistani market, Arun P. Sanghvi estimated the impact of power shortages in developing countries. He revealed that in Pakistan the resulting direct and indirect cost of power outages from 1984-1985 was 525 million dollars, representing a 1.8% reduction in Pakistani GDP.

In conclusion, while the need for small HPPs is largely derived from a political will to achieve energy security, in order to avoid unwanted tensions and conflicts, there is a necessity for the institutionalization of an inclusive and evidence-based approach to HPP authorization. Such an approach should highlight, in an objective and transparent way, the socio-economic rationale behind the authorization, accompanied by accurate estimates of the expected costs and the benefits to society (particularly those local communities most affected).

High-quality analyses of projects’ environmental impacts certainly have the potential to facilitate more informed and thus constructive debates, and moreover the opportunity to decrease manipulation. This, in our view, is the best course of action for future developments.

1 The summer period includes April, May, June, and July.

2 The duration of which varied between 3-16 of the day in different regions of Italy.