31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

11

October,

2019

Friday,

11

October,

2019

Friday,

11

October,

2019

Friday,

11

October,

2019

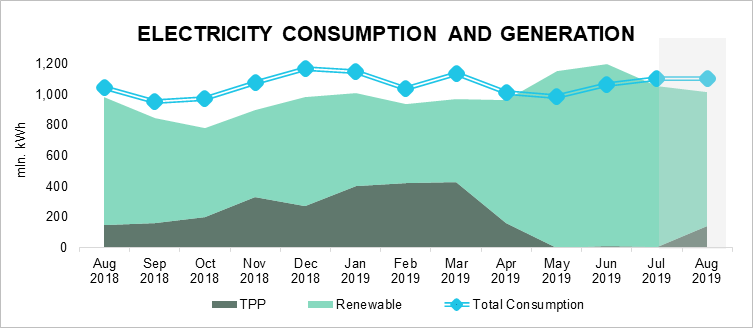

Historically, the main concern in monitoring the Georgian electricity market derives from the negative generation-consumption gap arising in the winter season. However, persistent electricity deficits over ten months between August 2018 and August 2019 suggest that the number of months characterized by a negative generation-consumption gap might be on the rise. Looking at Figure 1 below, generation can only clearly be seen to exceed consumption twice during the past 12 months, in May and June. This year has been the first time that Georgia has faced an electricity deficit even in July. Moreover, this July deficit was hardly negligible, reaching 54 mln. kWh and the gap not only remained but widened to 84 mln. kWh in August 2019.

Figure 1. Electricity Consumption and Generation

The expanding gap alone is not necessarily a negative sign. On the consumption side, the increased demand during the summer months might stem from Georgia’s transition towards such countries that experience peaking summer demand alongside winter peaks, possibly due to the increased use of air conditioners and expanding tourism. The widening gap, however, is not solely due to growth in demand, but to a decline in supply.

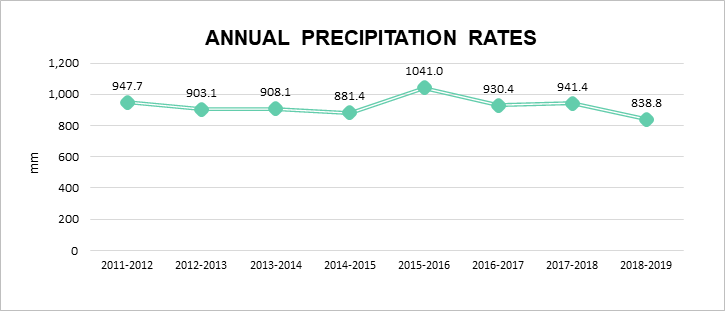

Due to the significance of hydropower generation in Georgia’s total electricity generation, we have decided to explore the evolution of precipitation rates over the last decade. According to data from 18 National Environment Agency (NEA) stations, the average precipitation rate in 2018-2019 was the lowest of the last eight years (11% lower than the previous 12 months), indicating decreased generation potential of HPPs. This could thus be translated into the generation deficit and an increasing generation-consumption gap for 2018-2019.

Figure 2. Annual Precipitation Rates1

Alongside the increasing trend of consumption, this can explain the increase in the generation-consumption gap, and why electricity generation growth has been unable to match demand growth, despite the improved hydropower generation capacity (beginning in August 2018 to August 2019 four seasonal2 and five small3 HPPs began to a contribute 3.5% of the total electricity generation during the summer season).

While lower precipitation last year may simply indicate a temporary crisis for the power system, it is important to consider that climate change is a core challenge for the modern world. According to the 2018 Global Climate Summary of the National Center for Environment Information (NOAA), the combined land and ocean temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.07°C/0.13°F per decade since 1880; however, the average increase since 1981 (0.17°C/0.31°F) is more than twice as great. In future predictions, it is estimated that by 2020 the global surface temperature will be more than 0.5°C (0.9°F) warmer than the 1986-2005 average, regardless of which carbon dioxide emissions pathways the world follows. Increased temperatures are expected to be reflected in a low concentration of water, drier days, and decreased generation potential. These factors create unfavorable conditions for countries that depend substantially on hydropower resources. As the major share of the total capacity of planned energy projects in Georgia originates from HPPs, recent developments ring a warning bell that should not be ignored by policymakers. As the country’s energy security must be maintained and strengthened, it is worth placing greater attention on other renewable energy sources, as well as policies to increase energy efficiency.

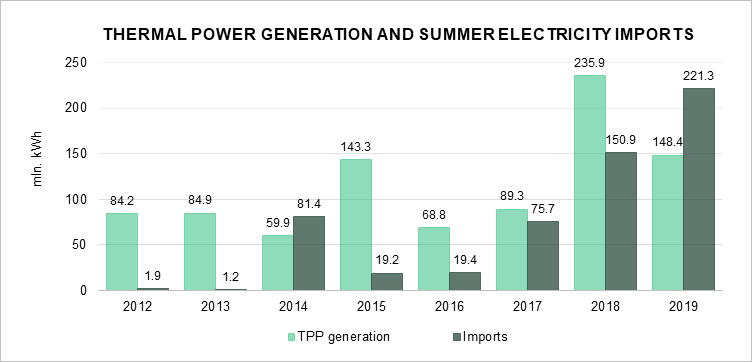

The new trend has significant implications for the evolution of Georgia’s energy security. A country is considered energy secure if it has secure access to the energy necessary to satisfy its consumption needs at relatively cheap prices. The security of access is at its highest when a country is self-sufficient. In the absence of self-sufficiency, the security of access can be increased by relying on a variable portfolio of suppliers. In the case of electricity, security would be achieved by minimizing the necessary imports of electricity and of fuel for thermal power plants (TPPs). The TPP generation and import of electricity over the last two summer periods (Figure 3)4 shows that the widening electricity generation-consumption gap has been filled with increased TPP production and with surged imports, thereby resulting in a reduction in the country’s energy security. Unfortunately, the Georgian portfolio of suppliers is still relatively concentrated.

Figure 3. Thermal Power Generation and Summer Electricity Imports

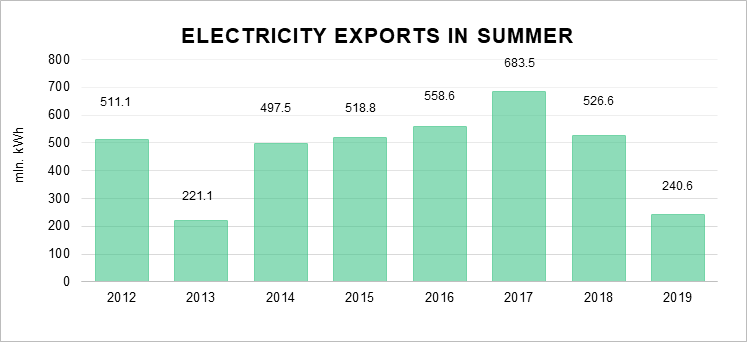

Due to such changing trends, Georgia has also seen a substantial reduction in electricity exports. This may be disappointing news for those hoping that increasing electricity exports would prove a strong driver of economic growth. Figure 4 shows the development of summertime exports over recent years; where, the summer of 2019 was the worst in terms of exports over the last six years.

Figure 4. Electricity Exports in Summer

In conclusion, increasing consumption, lagging investments in renewable energy sources (other than hydropower), and a lack of diversification make the Georgian power system less energy secure and more vulnerable to changing climate conditions. Georgian policymakers may wish to adopt a more prudent and forward-looking approach, aiming at minimizing the negative impacts of shocks that may yet affect the country. While we cannot precisely predict the future, we can at least ensure against such potential risks.

1 Starting from August of the previous year and ending in the following July, for example, 2011-2012 indicates precipitation rate from August 2011-July 2012.

2 Kirnatihesi, Oldenergyhesi, Mestiachalahesi 1 & 2.

3 Skurdidihesi, Jonoulihesi 1, Aragvihesi 2, Oro hesi and Avanihesi.

4 Indicating four months, May, June, July, and August.