This is the last issue of the Khachapuri Index column in 2012 (#44 this year and #74 overall since the project’s launch in June 2011). Therefore, we would like to wish our readers many causes for the magnificent Georgian supra in the new 2013, with a lot of khachapuri and wine.

The

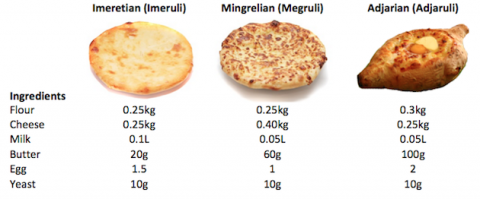

ISET Khachapuri Index is based on the prices of six ingredients used to cook the

Imeretian khachapuri

, which is considered to be the most common in Georgia. However, Imereti has no monopoly on khachapuri and most other Georgian regions have their own traditional recipes and cooking methods. The following types of khachapuri have received “official” recognition:

Imeruli, Acharuli, Megruli, Abkhazuri, Osuri, Svanuri and

Rachuli. While using roughly the same ingredients, all seven khachapuri differ in look, shape, and taste. Such diversity is not surprising given that Georgia has been divided by mountain ranges and – for much of its history – political borders. To this date, after many generations of geographic and social mobility, Georgians are very well aware of their historical roots and cherish ancestral traditions, including cuisine.

As families will be gathering for supra meals to celebrate the New Year they will be serving different types of khachapuri. In this special issue of our column, we present the recipes and compare the prices of the three most common khachapuri types: Imeruli, Adjaruli, and Megruli.

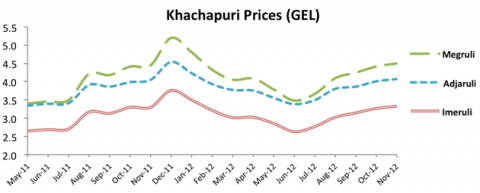

The distinctive feature of the Megruli recipe is the extra layer of cheese on top. With so much cheese, the cooking cost of the Megruli khachapuri is a) higher and b) more volatile than those of other regional brands. Cheese is the single most expensive khachapuri ingredient and it is also subject to very strong seasonal price fluctuations. Adjarian (or Acharuli) khachapuri is hard to mistake for anything else since it has an open gondola shape and is topped with a raw egg and butter just before serving (of course, this makes it particularly rich in these two ingredients).

The bad news for those preparing New Year supras is that the price of cheese (and khachapuri) reaches its annual peak in December. In part, this follows from the unsophisticated nature of Georgia’s dairy industry. A huge proportion of Georgian cows get “dry” in late fall, causing the price of milk and dairy products to go up. At the same time, the number and size of supras that Georgians organize during the New Year holiday season causes the demand for cheese (especially after the Orthodox Xmas, when the fast comes to an end) and other foodstuffs to skyrocket.

With cheese being much more expensive than other ingredients, we may ask why do the Megrelians do not switch to a more economical version of khachapuri, such as the Imeruli one? Are they richer compared to other regions? At first glance, this does not seem to be the case. According to GeoStat’s 2011 Integrated Household Survey data, the average income per household has been 697GEL in Samegrelo, which is lower than in Imereti (707GEL) and Adjara (742GEL). However, Samegrelo is the most homogeneous region of Georgia in terms of income per household. The Gini coefficient for Samegrelo is 0.42, while it is 0.45 and 0.50 in Imereti and Adjara, respectively. The fact the income is distributed more equally implies that a larger share of Megrelian families can afford an additional layer of cheese (and other goodies). Despite being poorer on average, Samegrelo has a higher median household income of 525GEL, as compared to 500 and 480GEL in Adjara and Imereti, respectively. Translation into plain English: 50% of Megrelian households live on incomes higher than 525GEL.

There may be another explanation for the extra cheese on top. Megrelians are said to be passionate about cheese. For instance, they are known for producing arguably the most delicious Georgian cheese variety - “sulguni”, which goes well together with another gem of Megrelian cuisine – “ghomi”. Ghomi is a common maize dish that has the consistency of stiff porridge and a fairly neutral taste (it is prepared without salt). It is consumed with chunks of sulguni that are allowed to melt and run deep inside the dish. Ghomi makes for a great carrier of additional flavors and is often used as a substitute for bread.

A happy and dietetic New Year!

The views and analysis in this article belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views

of the international School of Economics at TSU (ISET) or ISET Policty Institute.

27

მაისი

2022

27

მაისი

2022