31

მაისი

2023

31

მაისი

2023

ISET ეკონომისტი

პარასკევი,

18

იანვარი,

2013

პარასკევი,

18

იანვარი,

2013

პარასკევი,

18

იანვარი,

2013

პარასკევი,

18

იანვარი,

2013

Is inequality bad for economic development? There has been a lively debate on this issue. Some economists argue that inequality is necessary for economic growth, while others are against it. Relatively recent empirical studies have found that in countries with relatively low per capita income inequality hampers growth. One of the main ways in which high inequality negatively affects economic growth is social turmoil. Social discontent is translated into socio-political instability, raising political and economic uncertainty in a country, which in turn impedes private investments, both foreign and domestic. This kind of transmission mechanism seems to work in the Georgian context as well. A recent Growth Diagnostics study by ISET Professors Fuenfzig and Babych finds that political instability and country risk factors in Georgia are among the potential binding constraints to long-run economic growth. Insofar as inequality and poverty directly contribute to a political and institutional instability, addressing these issues should be one of the primary objectives of Georgian policymakers.

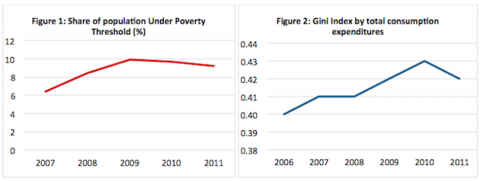

Some facts on growth and inequality from Georgia: Since the Rose Revolution Georgia has enjoyed high real GDP growth rates, averaging at about 9.3% in the period 2003-2007. Additionally, although its post-financial crisis growth rates were modest, Georgia weathered the global financial crisis relatively successfully compared to both its peer countries in the region and in Europe (see, for example, the 2012 Growth Diagnostics study). Nevertheless, it seems that this quite remarkable growth performance has not been pro-poor: unemployment has not decreased; poverty rates and inequality in the country still remain at high levels; the share of the population with incomes below the subsistence minimum has been fluctuating around 9% over the last three years. Inequality, as measured by the Gini index, has been slightly increasing since 2006 (with a negligible decrease only in 2011), indicating that growth did not “trickle-down” to the poorer parts of the population (see Figures 1 and 2).

Can a Kuznets curve explain these things? The pattern described above is somewhat in line with what Simon Kuznets argued in the mid-1950s on the relationship between growth and inequality. Kuznets claimed that at the stages of relatively low levels of economic development and thus, low levels of per-capita incomes, inequality may initially increase as the economy grows, but then the trend is likely to be reversed as the economy achieves sufficient development, thereby implying an inverted U-shaped curve (known as a Kuznets curve) relating inequality and growth.

The intuition behind this hypothesis is rather simple: economic development – such as moving from low productivity agriculture to more productive sectors such as manufacturing and services, and the adoption of new technologies –initially benefits only the minority of the population, thereby resulting in an additional income gap. As the economy grows further, the share of the labour force in the low productivity sectors gets significantly low and the productivity gains become even, leading to a decrease in inequality.

Obviously, the Kuznets curve says something useful about the dynamics of inequality and growth observed in Georgia. Assuming for the moment that Kuznets hypothesis holds in the Georgian context, it is reasonable to argue that Georgia, being a developing country with not so much per-capita income and with 56% of its labour force employed (better to say self-employed) in the low productivity agriculture sector, is currently on the upward-sloping part of the Kuznets curve. Importantly, the share of the rural population has been quite steady over the last 10 years, implying that the process of moving labour force from agriculture to more productive sectors has not yet been unleashed[1]. The fact then that there has been only a slight increase in the Gini index over the past decade is quite in line with Kuznets hypothesis. The slight increase in the Gini index itself can just reflect the fact that in recent years productivity gains in the agriculture sector were quite modest compared to those in other industries, such as the manufacturing or service sector, creating an additional rural-urban inequality gap.

“Overcoming” the Kuznets Curve: If Kuznets’ hypothesis is true (there has been some support for its existence in recent studies), then we will presumably observe even higher inequality in Georgia over the coming decades as the economy develops further and the service and manufacturing sectors require more labour. However, there are case studies showing that Kuznets’ relationship does not always hold. One such example is related to the East Asian Miracle when eight East Asian countries including the Four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore) saw rapid growth in the period1965-1990 without an increase in inequality, instead, poverty and inequality levels were reduced during this high-growth period.

In his paper “Some Lessons from the East Asian Miracle” Jozeph Stiglitz argues that the main reason why these countries managed to successfully “break” the Kuznets curve was their governments’ “right” intervention at both the start and in the later stages of development. In particular, Stiglitz considers (i) agricultural reforms (resulting in higher rural productivity, income and, thus, savings), (ii) educational reforms (providing universal literacy) and (iii) redistribution policies, to be the key factors elevating inequality in the East Asian countries. All these reforms, as Stiglitz argues, further accelerated growth through mitigating socio-political instability and thereby encouraging investments.

This experience seems quite relevant for the Georgian economy, where the rural population, comprising more than half of total the population, suffers from poverty and inequality the most. Thus, one of the first steps the Georgian government should undertake is focusing on the development of the agriculture sector to increase rural productivity (and thus income), which so far remains at dramatically low levels (agriculture contributes only about 9% to Georgia’s total GDP and the productivity level of this sector has not yet recovered to its 1992 level). This will ensure pushing GDP growth rates through both increased income levels in rural areas and reduced poverty and inequality.