30

ივნისი

2022

30

ივნისი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

ორშაბათი,

25

თებერვალი,

2013

ორშაბათი,

25

თებერვალი,

2013

Recent strikes of minibus drivers in Tbilisi have reminded all of us about the long-forgotten issue of labor rights in Georgia. Since the new government came to power at the beginning of October, employee protests have become a regular “inconvenience”. Some strikes lasted longer than others, as in the case of the Chiatura manganese mine and Poti port, generating significant losses for the Georgian economy. The situation reminded me of a year I spent as an exchange student in Thessaloniki, Greece, where walkouts by public and private servants became a daily routine. On some days I missed lectures due to a bus drivers’ strike; on other days I had to make my way through piles of garbage, holding my breath in support of striking Greek waste collectors.

Amending the labor code and bringing it closer to the standards of the International Labor Organization (ILO) is one of the key priorities for the new parliament. The Georgian legislators have recently introduced a project of the new labor code, however, despite great public interest in the subject, there has been little debate concerning the content of the proposed labor code and its possible economic effects.

It took independent Georgia six years to make the first amendments to the Soviet labor code. However, even after the 1997 amendments, the core of the code remained intact with communist-style provisions directly contradicting the free-market spirit and principles.

The labor code has been finally revamped after the “Rose Revolution”. In 2006, the new government abolished almost all of the regulations concerning the labor market. Containing only 55 paragraphs, the Georgian labor code appeared to be among the world’s shortest and most liberal. Ignoring recommendations from the European Commission and ILO standards, the Georgian government chose to stick to the more market-oriented US model. The labor code adopted in 2006 (which is still in force) gives employers the freedom to dismiss employees without supplying any explanation. Georgian employers are only obliged to provide a one-month severance pay, something which presents no significant relief to those who have lost their jobs.

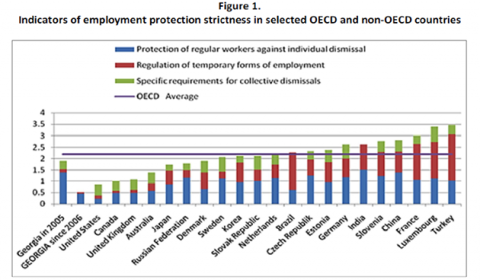

Figure 1 shows Georgia’s score (0.51) and relative position on OECD’s Employment Protection Strictness ranking (the scale varies from 0 to 6, a higher grade standing for stricter regulations). For comparison, the OECD average stands at 2.2. Prior to 2006, the index for Georgia was 1.9, similar to that of Denmark or the Russian Federation. (It is of course debatable how much actual protection the old labor code provided in the lawless and economically depressed pre-2006 realities.)

The initiative to amend the labor code comes from “Georgian Dream” quarters in consultation with the labor unions and, consequently, the new code contains several improvements in terms of labor rights protection. The new provisions concern maximum working hours, compensation for overtime work, regulation of fixed-term employment contracts, and dismissal procedures.

Economic evidence regarding the impact of labor regulation is mixed. In general, views fall into two broad categories: the so-called Distortionists and the Institutionalists. The Distortionist view (Besley and Burgess, 2004) is that heavy governmental involvement in the labor market distorts the “optimal world”. Distortion might come from:

On the contrary, the Institutionalist view is that by reducing the ability of employers to dismiss employees, societies insure workers against short-term failures and recessions, thus boosting employee loyalty and strengthening the stimuli to engage in value-maximizing activities and innovation in the workplace (Acharya and Baghai-Wadji, 2009).

While not introducing a minimum wage requirement, the new labor code does include stricter non-wage regulations, which will certainly make the life of Georgian employers more difficult. More detailed employment agreements, less flexibility to keep employees at work beyond normal working hours, and stricter rules for dismissal will all increase the rigidity of the labor market and push up labor costs.

If enacted, the new labor code constitutes an interesting “field experiment” allowing to test which of the opposite views concerning stricter labor market regulation has greater validity in a development context. I doubt, however, that the new labor code, in and of itself, will have a significant impact on job creation, economic growth, and welfare. Firstly, the proposed code remains quite liberal compared to the majority of the European states; and secondly, investment and job creation, etc., are far more likely to be driven by considerations of political stability, access to markets, rule of law, and property rights, which most observers consider to be the major obstacles for Georgia’s economic development.