30

ივნისი

2022

30

ივნისი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

სამშაბათი,

05

მარტი,

2013

სამშაბათი,

05

მარტი,

2013

The ability of families to meet their most basic needs is an important measure for the development of a country. Poverty touches on questions of human dignity and fairness in society, but beyond that, poverty causes problems that may impair long-run economic prospects, like crime, social unrest, and underinvestment in human capital. Given the libertarian agenda pursued by the United National Movement since the Rose Revolution, one might suspect that Georgia has a poverty problem. Is this true?

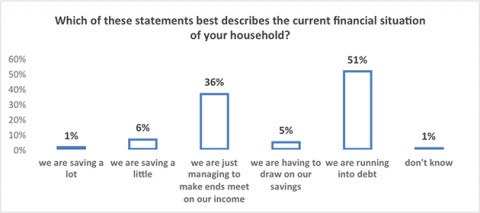

According to the ISET Consumer Confidence Index of February 2013, 51% of respondents report that they are running deficits, while only 36% manage to make ends meet on their income (see the chart). Likewise, the GeoStat household survey includes the question: “How do you measure your material status by income?” Here, in the year 2011, 43% of the respondents replied that their income is enough only for catering, while 29% answered that they more or less manage to satisfy their daily demands. 45% consider themselves to be poor, while 46% think that they belong to the middle class.

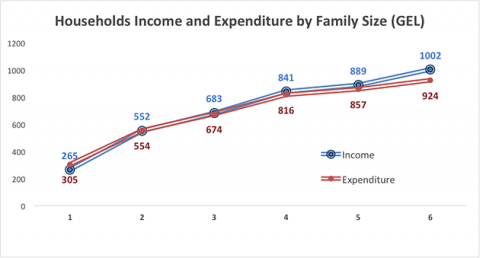

Looking at the integrated household survey data of 2011, for the majority of families expenditures are very close to or lower than their incomes. Yet not all families are equally prone to poverty. While for the average single-member family expenditures exceed income by 40 Laris per month, as family size increases the average budget moves towards a surplus. For the average family with 6 members, the monthly income exceeds the expenditures by almost 80 Laris (see the chart). Arguably, adult family members can contribute to the family’s income, but the expenditures do not increase proportionally. There may be “economies of scale”, i.e. families share the same apartment, they all use the heating system, cook in a bigger pot, etc. which makes life cheaper per person.

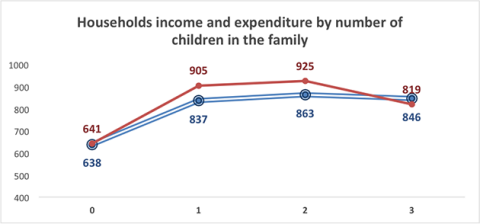

When it comes to the number of children, household income is pretty high in families with one or two children compared to those without children or with three kids. The gap between income and expenditure is highest when there is only one kid in a family. Here the causality may be reverse – families with very low income may abstain from getting children, which would strain their budget even more. When there is sufficient money available to sustain children, people let their families grow.

In Western Europe, a comprehensive system of benefits and transfers not only alleviates grave poverty but makes life easier for substantial parts of the population. In 2008, almost 10% of the German population received social transfers. These payments can be quite generous – in 2012, an unemployed couple with two children received about 1,800 Euros per month in social transfers (almost 4,000 GEL).

Likewise, in Western Europe redistributive policies are ubiquitous, ranging from compulsory social insurance to tax rates which rise progressively in income. In Germany, one has to pay 14% tax on the first Euro which exceeds 8,004 Euros yearly income, and one ends up paying 42% of every Euro earned above 52,882 Euros.

In contrast, the Georgian government hardly interferes with the income distribution generated by markets. There are no social transfers and the tax rate is flat as a khachapuri.

Whether this is good or bad is controversial, and we do not take sides. Clearly, the social welfare states of Western Europe have various adverse effects, like severe incentives not to work, special kinds of fraud (“milking the welfare state”), and additional immigration induced by welfare payments. On the other hand, also a libertarian policy like the one adopted by Georgia in the last 10 years comes with a social price tag, despite its successes in generating impressive growth rates.

The figures mentioned above refer to absolute levels of income. While it corresponds to the intuition of most people that poverty is the absence of wealth or income, to be measured in absolute terms, among economists and sociologists it is common to report relative poverty. The OECD, for example, defines a household to be poor if it has an income that is below 60% of the median income. The underlying idea is that poverty is not only an economic but rather a social state, which says something about the potential of an individual to fully participate in society. Participation means not only having food and shelter, but generally taking part in the public and cultural life, e.g. to be mobile, to have a telephone, to have television, internet, and even to occasionally buy a cinema ticket or go to a restaurant. According to this notion of poverty, the poor are those who are deprived of participation in their society due to a lack of material resources.

Defining poverty in a relative way has bizarre effects. As long as income in a society is not fully equal, there will always be people who earn less than 60% of the median income. So whatever the income is, there will always be poverty. Indeed, according to this way of measuring poverty, more than 15% of the Germans are “poor”, despite the generous welfare transfers described above.