27

მაისი

2022

27

მაისი

2022

ISET ეკონომისტი

სამშაბათი,

07

მაისი,

2013

სამშაბათი,

07

მაისი,

2013

სამშაბათი,

07

მაისი,

2013

სამშაბათი,

07

მაისი,

2013

Once considered the most dynamic sector of the Georgian economy, the banks have recently become a target for fierce criticism by Georgian policymakers and the media. In early March, NBG president Giorgi Kadagidze called on commercial banks to reduce interest rates on corporate loans to help accelerate the country’s economic recovery. Bloomberg reports him saying that “interest rates on corporate loans are inappropriately high, between 24 and 30 percent, whereas they should be around 12 percent”. Legislative initiatives seeking to cap interest rates, weaken the mortgage liens and enforce “truth-in-advertising” are also said to be in the works.

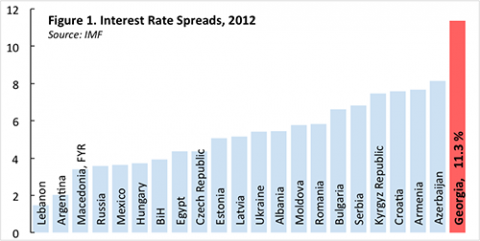

Indeed, at 11.3%, the interest rate spread (the difference between lending and deposit interest rates) in Georgia is much higher than in most other transition economies, including our immediate neighbors, Armenia and Azerbaijan. High spreads imply high-interest rates on loans, hampering private investment and economic growth. But what are the reasons for the high lending rates (and spreads) and how realistic are the expectations to have them slashed by as much as 50%?

Several factors could explain high financial intermediation costs in developing countries. These include: unstable macroeconomic environment, low savings, weak competition in the banking sector, the high share of Non-Performing Loans (NPLs), high reserve requirements imposed by the national banks, high non-interest costs (inefficiencies) in the banking sector, and general political risks facing the country.

In an unstable macroeconomic environment characterized by high and unpredictable inflation, financial intermediaries will charge high-interest rate margins to avoid erosion in the real value of outstanding loans due to a sudden hike in inflation. Similarly, large macroeconomic volatilities could also cause businesses to default on their loans thereby prompting banks to increase lending interest rates far above deposit rates. In recent years, however, Georgia has been living with very low and stable inflation, suggesting that macroeconomic risks cannot explain the persistence of high lending rates and interest rate spreads.

Georgians are saving very little and scarcity of financial resources at the banks’ disposal could also be considered a cause of high lending rates. Yet, many Georgian banks have international shareholders and can borrow in the international financial markets, keeping them well-capitalized and liquid.

The “monopolization” argument has been quite popular among politicians (and not only) as an explanation for the persistence of high-interest rate margins. However, by any conventional measure of market concentration, the Georgian banking sector is fiercely competitive. Moreover, the Georgian banks are not as profitable as would follow from the monopolization argument. In 2012, for instance, return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) – two conventional indicators of profitability – stood at 1.3 and 7.9%, below the average for our selected countries (1.5 and 12.9%, respectively).

A high ratio of Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) could also explain the high-interest rate spreads. Facing high levels of NPLs, banks would set high-interest rate margins to cover NPL-related costs. However, Georgia’s NPL ratio is fairly low by international standards. For instance, in 2011, NPLs-to-banks’ total gross loans ratio stood at 4.5% – far below those in the majority of benchmark transition and developing economies with much lower interest rate spreads (only Argentina, Mexico, Armenia, and Estonia from our sample reported slightly lower NPLs-to-total loans ratios).

Similarly, high reserve requirements imply foregone interest income that banks could have earned by lending additional money. Yet, reserve ratios are not particularly high in Georgia compared to other emerging markets. Since 2010, the required reserve ratios have been set at 10 and 5% on deposits in domestic and foreign currencies, respectively. This is higher than in the Eurozone, where the minimum reserve requirement is as low as 2%, but not sufficiently high to explain the observed lending rates in Georgia. For instance, Romania, Bulgaria, Mexico, and Croatia – countries with fairly low-interest rate spreads – have similar or higher reserve requirements.

Having ruled out the above channels, we are left with only two candidates to consider: high operational costs (inefficiency) of the banking industry and the general political risk facing Georgia.

Given the small size of Georgia’s domestic market and relatively modest levels of financial development (reflected in low deposit-to-GDP and loan-to-GDP ratios – 37 and 30%, respectively, in 2011), Georgian banks are unable to benefit from economies of scale and face very high costs. According to our estimates, while loans average about 4,200GEL, 50% of all loans are less than 1,000GEL. Administering such a large number of tiny loans imposes a very high burden on the Georgian banks, directly contributing to high-interest rate spreads.

The second reason for the high intermediation costs is the high cost of capital due to a combination of political and social risks as measured by Georgia’s country credit ratings (well below investment grade). These risks are partly related to geopolitical considerations (Georgia’s conflict with Russia and other dormant conflicts in the South Caucasus region) and partly to high unemployment, income inequality, and poverty, as well as perceptions of weak property rights and a lack of judicial independence. The political and social risks translate into high intermediation costs and lending rates because Georgian banks heavily depend on borrowing – at a very high cost – in international markets.

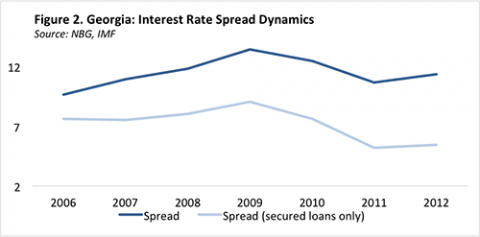

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of interest rate spreads for all types of credit and, separately, for collateralized (secured) loans only. The latter measure is invariant to the credit portfolio of banks and thus better reflects the changes in the costs of capital facing the Georgian banks. The two lines are very well synchronized, going up at times of war, as well as political and macroeconomic uncertainties. The most recent increase in the spreads could reflect political risks in the run-up to the parliamentary elections of October 2012.

To summarize, high lending rates indeed impede investment and growth. Yet, to the extent possible, the Georgian government should treat the root causes of this problem, not its symptoms. The banks are not the enemy of the people, and should not be attacked for populist reasons. For example, a politically motivated cap on lending interest rates would lower profit margins in the banking sector, reducing the volume of private credit to the economy. Calling on banks to lower interest rates will not help unless such calls are accompanied by measures to reduce the social and political risks facing the Georgian economy.

There are many areas in which government interventions could be quite effective. For example, the government could consider measures to improve the protection of property rights and promote judicial independence. It could also mitigate social and political risks by paying greater attention to rural development and facilitating job creation in the cities. At the same time, the Georgian public should not expect miracles. Financial development is a slow process, particularly so in the presence of risk factors that are beyond the Georgian government’s control.