31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

09

November,

2020

Monday,

09

November,

2020

Monday,

09

November,

2020

Monday,

09

November,

2020

Pressure on environmental conditions has been increasing over the years in Tbilisi due to several factors:

• Population increase – according to the National Statistics Office of Georgia (GeoStat), the capital’s population has increased by 8% over the last ten years;

• Tbilisi is the center of Georgian business operations – GeoStat reveals that, by January 2020, 42% of economically active organizations were located in Tbilisi;

• These two factors are strongly associated with high levels of activity in the construction sector – according to GeoStat, 48% of construction permits issued in 2019 were allocated in Tbilisi. In many cases, construction projects are notably developing at the expense of city green space;

• Tbilisi has the highest share of vehicle holders – the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia shows that 36% of registered vehicles are in Tbilisi.

Given the increasing pressure on the city’s environment, action should be taken to provide a healthier and more habitable space. The development of urban parks is therefore one viable option. However, the trend over the last decade has gone in exactly the opposite direction, with green space per capita decreasing dramatically; estimations from Tbilisi City Hall data highlight that per-capita green space1 decreased from 5.6 to 1.3m2 between 2010-2018 (well below average European standards 10-15m2).

The literature suggests that green spaces and nature-based solutions represent the most efficient approaches for improving the quality of city life (World Health Organization, 2017). Urban parks, defined as delineated open space areas, mostly dominated by vegetation and water, and generally reserved for public use (Maruthaveeran, 2015), is considered an excellent method of expanding urban citizens’ exposure to nature. Historically, the primary role of urban parks has been to improve environmental conditions in cities by reducing urban heat, buffering noise, contributing to better air quality, and supporting ecological diversity. The significance of urban parks, however, is not limited solely to an environmental perspective.

Studies show that urban parks have a key role in supporting socialization and recreation among city residents, and this role has at times even grown to overshadow the environmental impact – with recreation being defined as an experience that results from freely chosen participation in physical, social, intellectual, creative and spiritual pursuits that enhance individual and community wellbeing (Elis, 2016). The international best practices of urban parks, such as New York Central Park, Boston Common, or Monsanto Forest Park in Lisbon, also reinforce that parks can become a key defining feature within a city. Regardless of the differences in their arrangement, a common characteristic of these parks is the diverse array of amusements for visitors, including gardens, museums, and attractions. Nevertheless, there is always also plenty of green space and leisure areas for friends and families to gather, and which attract daily visitors.

Although urban parks are considered valuable for their significant role in social development, they are not usually perceived as profitable investments. They require substantial capital and maintenance costs, which are usually never offset by financial revenue, consequently, they are rarely an appealing investment opportunity for private investors. Thus, the majority of urban parks are provided by local governments as local public goods.2 Since local authorities are the main entities responsible for the provision, development, and management of urban parks, it is worthwhile considering city residents’ preferences during the planning process.

The Mayor of Tbilisi recently presented a rehabilitation project for the former Hippodrome Park, aimed at transforming it into Tbilisi Central Park, which would thus increase the availability of recreational zones in the city. The suggested plan has, though, become a highly debated issue. While part of society is excited by the concept, others are strongly opposed to the plan. Most opponents believe that although rehabilitation is required, they fear that the development of a park in the direction suggested will remove its primary recreational function.

Consequently, in order to better examine local societal preferences, we designed a survey and shared it through social media. We asked respondents to offer their opinions on the proposed Tbilisi Central Park project, and on existing parks and green spaces in general. By the end of the exercise, we had collected the responses of 224 Tbilisi residents.

The survey results suggest that the existing parks are quite popular (40% of respondents visit parks and other green spaces several times a week). Moreover, 93% of respondents claim that they would visit parks more often still if they had such spaces in the vicinity of their work or homes. Whereas other respondents who reported that they would not frequently visit more local parks believe there are already parks and green spaces close enough to their homes and workspace.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the related restrictions, have significantly increased the utilization of public parks, and appreciation of this public good; 58% of respondents state that during the pandemic it has become more important to be able to visit green spaces. Nonetheless, only 24% reported managing to visit parks more often, largely because they had no local access to such places. Finally, 99% of the individuals surveyed believe that there is a need for more urban parks and green space in Tbilisi. These results therefore clearly support the idea that more green areas need to be developed throughout the city.

The respondents were also asked to evaluate the rehabilitation project of the former Hippodrome Park, attributing it a score between 1 to 10. Of the respondents, 52% evaluated the project between 1-5 (a negative evaluation), while the remaining 48% assessed between 6 and 10 (positive), confirming the split public opinion.

Examining the respondents’ answers in greater detail reveals that the main reasons for split public opinions are the characteristics of the suggested park. The new Tbilisi Central Park is expected to be divided into 26 different zones, including a food zone, an education center, alongside fountains and car parking zones. Thus, many of these “improvements” are likely at the expense of green areas, those currently used by residents for various recreational activities. This, however, is in stark contrast with the priorities highlighted by our respondents; with 61% claiming that the most urgent action should be increasing green space within the existing urban parks (i.e. grass, trees, etc.); followed by the need for multifunctional zones (28%); more space for sports activities (7%); and other basic comfort elements for visitors, such as the provision of drinking water and comfort stations (4%).

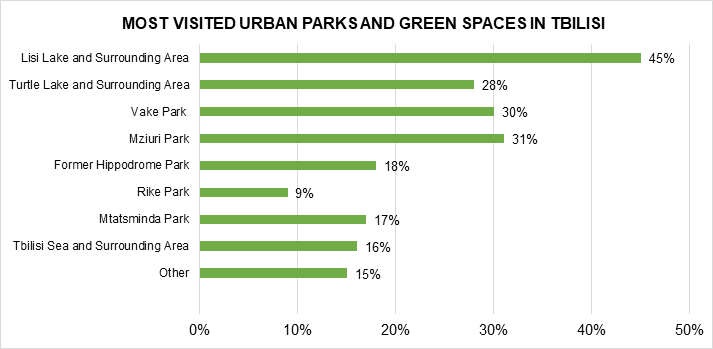

Local preferences are further confirmed by the fact that people tend to visit spaces with a greener environment (Graph 1), even if it is far from their living or working areas. Of those who usually visit greener spaces, such as Lisi Lake, the Hippodrome park, Tbilisi Sea, etc., 39% state that, even though such places are not near their neighborhoods, they go because they enjoy the environment. Furthermore, most respondents who indicated other preferred locations (beyond the options provided), visit either small parks in their neighborhoods or forest parks, such as Dighomi and Krtsanisi Forest parks, which also confirms their inclination towards greener environments.

Graph 1. Most Visited Urban Parks and Green Spaces in Tbilisi3

In summary, rehabilitation of the former hippodrome territory itself is a positive initiative. The main reason for any controversy seems to be that the planned infrastructural development does not necessarily meet societal needs or preferences. Our small survey suggests that any benefits could be magnified if the preferences of residents were better incorporated into the Central Park planning process; by minimizing the loss of green areas and preserving as much of the existing landscape as possible in order to maximize people’s exposure to the natural environment in the heart of Tbilisi.

Bibliography

Cranz, G. (2014). Defining the sustainable park: A fifth model for urban parks. Landscape Journal, 102-120.

Elis, D. (2016). The roles of the Urban Parks System. Panama City: World Urban Parks.

Maruthaveeran, S. N. (2015). Benefits of Urban Parks – A systemic Review. IFPRA.

World Health Organization. (2017). Urban green areas – a brief for action. Copenhagen: WHO.

1 Per-capita green space is a green space area divided by the total population of the city.

2 Public goods refer to a commodity or service that is made available to all members of society. These services are administered by governments and paid for collectively through taxation.

3 The sum of responses exceeds 100% because respondents could select more than one choice.