31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

16

November,

2020

Monday,

16

November,

2020

Monday,

16

November,

2020

Monday,

16

November,

2020

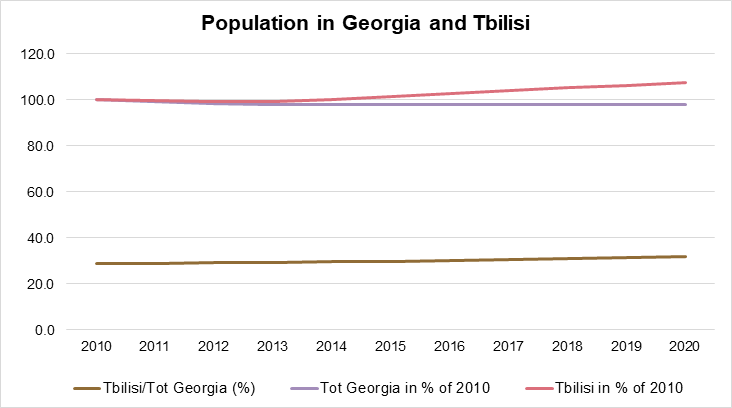

Until 2014, the population of Tbilisi remained more or less constant, even slightly decreasing at the same rate as the population of the country as a whole. Since 2014, though, there has been a marked migration to the capital as seen in the graph below.

A similar trend is observed all over the world. On average, a little over half of the global population currently lives in cities and, according to a recent report by the UN, that figure is expected to increase to 66 percent by 2050.1 Georgia is almost there: taken together, the country’s 7 largest cities account for 1.8 million people. According to the most recent data, 59 percent of the country’s population lives in urban areas, while Tbilisi accounts for 32 percent of Georgia’s population2.

Like other major cities across the world, Tbilisi already faces increased pressure on its infrastructure due to rural-urban and periphery-center migration. This pressure will continue to rise.

There is no denying that urbanization makes cities richer. Newcomers attracted by the opportunities that the city offers start businesses or join growing companies, which fuels all sectors of the local economy. The main challenge is to tax this growth so that cities can continue to function. That includes generating enough money to finance the maintenance and rehabilitation of the existing infrastructure as well as its extension to accommodate migrants. Without this, more substandard housing settlements could appear, bringing no taxes but potentially creating trouble. Indeed, as any resident of Tbilisi knows, the dire state of the city’s infrastructure coupled with the lack of proper urban planning has already resulted in the proliferation of substandard settlements and sustained the problem of the “kamikaze loggias” inherited from the 1990s, where many families continue to live3.

This post comes at a time when the Government has recently adopted the 2020-2025 strategy on decentralization. It sketches some of the hard facts that will need to be addressed as the authorities compound this strategy with specific policy options.

The standard economic argument is that large cities should capture (through taxes) a part of the value-added which attracts migrants to the city in the first place. The taxes would then be used to invest in (and maintain) the infrastructure that generates the added value. In theory, decentralization of the financing and delivery of local public goods should lead to better governance by improving the following: the efficiency of resource allocation; accountability; and cost recovery.4 As for obtaining funds, municipalities can potentially draw on three sources:

Empirically, the evidence in support of better governance as a result of decentralization is mixed, often due to a combination of factors. These include human resources, who at the subnational levels are not sufficiently trained to handle the complexity of the tasks they are supposed to perform, which sometimes leads to corruption with high social costs (Mauro, 1995, Tanzi and Davoodi, 1998).5 It is therefore crucial to properly assess the comparative advantages of each subnational level in order to assign their responsibility for providing government services to the lowest level of government that can do so efficiently.6 This is not easy and the issue has been addressed very differently all over the world.

The Soviet Union had a convention of privileging the development of infrastructure in large cities (prime examples: Moscow and Leningrad7) along with limiting mobility into the metropolises via a strict “propiska” (residency permit) system. At the same time, smaller cities were often organized around some form of industry (sometimes around a single plant or factory). After the fall of the Soviet Union, these industrial activities were not maintained, the “propiska” system was largely abandoned, and this has accelerated the movement to large cities.

Tbilisi has moved on since the break-up of the Soviet Union and, in many ways, it now offers the amenities of a modern city. Likewise, the Soviet infrastructure it inherited has been upgraded in many places. Yet, it has been decaying in others and it is obvious that the city’s infrastructure will require a complete overhaul in some areas. Major capital investments will also be needed in addition to the regular maintenance for more recent investments. In addition, Tbilisi will have to invest in creating infrastructure on the outskirts of the city.

The task seems daunting, especially considering that Tbilisi currently accounts for over 50% of Georgia's economic activity while its budget is a mere 4% of its contribution (about 1.8% of the overall GDP). In 2019, about a quarter of Tbilisi’s budget (around 81 mln USD) went to transport infrastructure-related expenses, including maintenance and restoration (which accounted for 47 mln USD) while about 20% of the city’s budget went to infrastructure-related expenses, including the rehabilitation of damaged buildings.

This is clearly out of line with the financing needs of a smoothly functioning (and growing) city and the current constraints on Tbilisi’s possible sources of financing make it virtually impossible to address its needs. This issue will have to be addressed in the strategy.

Not really. Tbilisi can count on an important asset. A recent IMF mission visited Georgia in early 2020 as part of an exercise to boost the quality of data for the Residential Property Price Index in Tbilisi. The exercise revealed that the price per sqm had been undervalued in the old series and that a significant increase has been observed since early 2019, both for flats and detached houses. This trend reflects a number of economic factors, including some that are associated with the increased value that people can gain from living in the capital or migrating to it.

How can one capture the wealth that originates from living in Tbilisi? How can one supplement this with other sources of funds? What is happening in other countries that share the same heritage and have a similar population distribution? An ISET-PI research team has recently undertaken a comparative study to look into these issues. We invite you to follow the Policy Pulse newsletter and the ISET-PI Facebook page to track the upcoming releases.

[1] World Cities Report 2016, Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures.

[2] Source: Geostat, Population by regions and urban-rural settlement, 2020

[3] The “kamikaze loggias” and their proliferation was a phenomenon very typical to the 1990s. Currently, these extensions are prohibited, but the problem continues, as families continue to reside in this type of housing.

[4] See e.g. Decentralization, Governance and public services: The impact of institutional arrangements, O. Azfar et al., IRIS Center, University of Maryland, 1999.

[5] Mauro, P., 1995, ‘Corruption and Growth’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, and Tanzi, V. and H. Davoodi, 1997, ‘Corruption, Public Investment, and Growth,’ IMF Working Paper 97/139 (Washington DC).

[6] « Subsidiary principle » or « decentralization theorem », see Oates (1972, 1999).

[7] Becker, Charles, S. Joshua Mendelsohn, and Kseniya Benderskaya. Russian urbanization in the Soviet and post-Soviet eras. Human Settlements Group, International Institute for Environment and Development, 2012.