30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

26

November,

2012

Monday,

26

November,

2012

Monday,

26

November,

2012

Monday,

26

November,

2012

In his blog post “The puzzle of agricultural productivity in Georgia and Armenia”, Adam Pellillo raises the following question:

Georgia seems to be the only former Soviet republic in which agricultural productivity hasn’t returned to or exceeded its level in 1992. As of 2010, agricultural productivity stood at only 77 percent of where it was at nearly two decades ago. Why hasn’t agricultural productivity improved in Georgia over the past two decades, while it has at least recovered in every other former Soviet republic? It is even more puzzling to consider why agricultural productivity has grown by nearly 200 percent in Armenia since 1992, while it has declined in Georgia since then.

Adam’s post drew quite a few reactions from the agricultural business and economics community. These fell into three categories.

Type A reactions focused on the reasons (some well known, some less so) for the low productivity in the Georgian ag sector such as “civil war and many years of lawlessness”, “loss of the Russian market”, “land fragmentation and lack of cooperation among small farmers”, “low priority on the government agenda for so many years”, “collapse of irrigation and drainage systems”, “lack of inputs, technology, and knowledge”, “low commercialization of ag. output”.

Type B reactions (fewer in number) focused on what could have worked so well in Armenia. Possible candidates are “better utilization of Soviet-era infrastructure, including irrigation”, “higher concentration of agricultural machinery”, “better ability of the country’s processing industry – such as the local brandy industry – to add value”.

Type C reactions, including one by Adam himself, were somewhat skeptical about the accuracy of the underlying data. For instance, an Armenian economist commented that “when comparing the rural life stories of our Georgian and Armenian students I did not get the feeling that the Armenian farmers’ standard of living is several times higher than that of their Georgian partners. Both groups are more similar than different to each other”.

To find the truth, we consulted two senior international statisticians working to improve the quality of agricultural statistics in Georgia and Armenia. Both tend to subscribe to the skeptical view. In particular, they suggested that the Georgian agricultural statistics are based on a rigorous survey of farmers that draws a fairly accurate picture of output and productivity concerning all the main crops. The Armenian ag statistics, on the other hand, are collected using a “reporting system based on community books that may still be influenced by the Soviet style of thinking, with a political pressure to report about increased production levels”.

Now, if Armenian statistics are truly unreliable what’s the point in using Armenia as a benchmark for Georgia (or any other country for that matter)? In despair, we turned to the (higher value) Georgian statistics.

Georgia consists of several regions all of which (except Tbilisi) have a very sizeable share of the labor force (self) employed in agriculture. The regions specialize in different types of agricultural production (crops, husbandry) due to radically different climate and soil conditions. Now, since productivity changes could not have been uniform across all subsectors, we thought that something interesting could be learned about the puzzle of agricultural productivity from a comparison of income per household across Georgia’s regions.

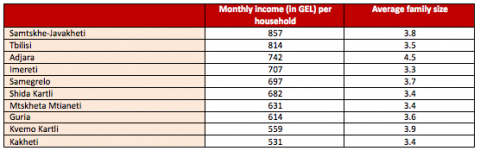

To our great surprise, instead of telling us anything about the evolution of agricultural productivity, the data are once again pointing in the Armenian direction. According to 2011 GeoStat household survey data, the region with the highest income per household (857 GEL) is Samtskhe-Javakheti. Not Tbilisi, not Samegrelo or Adjara. Samtskhe-Javakheti.

For those who don’t know, Samtskhe-Javakheti is the only region of Georgia where Armenians are in a majority (Tbilisi has the second largest Armenian population). Reflecting this demographic reality, the GeoStat sample of the Samtskhe-Javakheti region includes 198 Georgian and 477 Armenian families.

One might think that Armenian households are simply larger, but with 3.8 members per household, Samtskhe-Javakheti is not far from the national average (3.6).

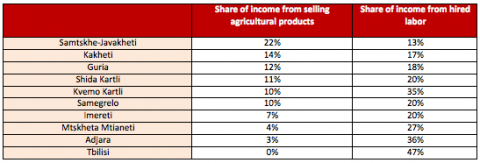

Samtskhe Javakheti does stand out on quite a number of parameters reflecting or affecting agricultural productivity:

There is no escape from the Armenian productivity factor also when one compares the incomes of Armenian and Georgian households within the Samtskhe Javakheti region (who thus operate in very similar conditions). The average income of the surveyed Armenian households in Samtskhe Javakheti is 923 GEL as compared to 729 GEL for Georgian families. Armenian households own 2.5 times more land on average (1 ha compared to 0.4 ha).