31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Thursday,

31

January,

2013

Thursday,

31

January,

2013

Thursday,

31

January,

2013

Thursday,

31

January,

2013

Can Georgia stimulate investment in electricity-intensive sectors by providing cheap electricity? To answer this question one has to first analyze the behavior of the wholesale electricity market during the past 3 years.

According to the order of the Georgian Ministry of Energy on the “Electricity (Capacity) Market Rules”, a “Direct Customer” (or one who buys electricity wholesale) is someone who, for their own needs, consumes 7 million kWh of electricity per year (As this amount is approved with basic directions of the state policy in the Energy Sector).

Theoretically, an advantage of being a direct customer is that you can have a direct contract with a power generator for the delivery of a certain amount of electricity instead of getting it from a retailer. So, big companies providing energy-intensive goods/services (such as companies involved in the aluminum industry) could benefit a lot from this arrangement as it is an opportunity for them to get cheaper electricity (compared to what they could get without having a chance for a direct contract) and significantly reduce their expenditure on electricity. Power generators in turn could get better deals in the event of there being much competition for their product. However, the ideal situation not always is observed in real life and there might be obstacles related to electricity demand and supply or to regulation that prevent such trade from taking place.

| Direct customers are allowed to buy electricity directly from power generators with direct contracts. For direct customers, one special issue here is the need to precisely forecast their future demand for electricity. In case of a mismatch between contracted power and actual consumption, the “Electricity System Commercial Operator” (ESCO) comes in. When the electricity bought through a direct contract is less than actual consumption, the company buys necessary additional power from ESCO with predefined standard conditions. On the contrary, when there is a situation of lower demand than was predicted, the power plant is not obliged to refund the buyer. |

According to the “Electricity System Commercial Operator” (ESCO) in 2012, there were seven active direct customers (three of which are state-owned companies) eligible for direct purchase of electricity from power plants (but this does not mean that it is mandatory to have direct contracts):

A person well aware of the situation in the Georgian business sector may wonder why some other companies involved in energy-intensive activities do not appear on this list. Some of them (Sakcement, Energy Invest (Azoti), Rusmetali, Geostili ) used to be direct customers before 2012 but last year they did not use their option to have direct contracts with electricity generator utilities. Why have such companies chosen a (potentially) more expensive option of production?

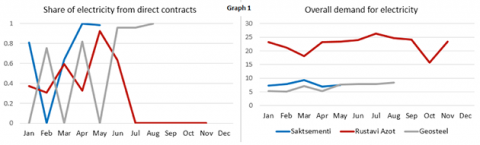

In the year 2010 each of those companies, except Rusmetali, started as direct consumers and a significant share of their demand was met with electricity bought with direct contracts. As seen from graph No.1, they seem to have experienced a problem of unstable supply or some internal reasons. The share of electricity coming from direct contracts fluctuated significantly, despite the fact that overall demand was somehow smooth. So, having unstable sources could be one reason for such companies not being satisfied with direct contracting.

Another obstacle linked to the supply side is the absence of cheap electricity, particularly in the last 3 years when the generation of the biggest and cheapest Hydro Power Plants in Georgia, Enguri and Vardnili, has decreased dramatically. This made cheap electricity available on smaller scales. Monopolies in the electricity distribution stage could be another obstacle. Distribution companies that also own generation utilities are not willing to give companies access to cheaper sources of electricity as doing so would reduce their profits.

The final price of electricity is also affected by regulations. Being a direct consumer has additional costs (such as related to predicting the demand and signing agreements with the transmission, distribution, and market operators. Finally, this leads to a lower margin between the price of electricity from retailers and power plants, which makes it less profitable to have direct contracts with power stations.

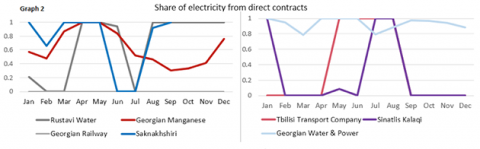

The current situation is depicted in graph No.2. Only Georgian Water & Power (GWP) has a smooth share of electricity coming via direct contracts. This fact could be explained by the fact that GWP also owns Jinvali hydropower plant, which could work for the company. In contrast, the Georgian railway has no direct contracts and it buys its electricity from ESCO. Two companies, Sinatlis Kalaqi and TTC, owned by Tbilisi City Hall fully satisfy their demand with direct contracts in the summer period (when electricity is cheaper). In addition to the reasons mentioned above, this could be linked to the inefficient functioning of state-owned companies.

Looking at the direct contract pattern of Saknakhshiri, one may guess that it will be the next company to reject being a direct customer.

In summary, there seem to be different obstacles for businesses to access cheap electricity in Georgia. Either the absence of it or the problem of access to it (or both) exist and needs to be addressed. The state should take decisive measures to somehow deal with these issues if there is an interest in attracting investment in energy-intensive sectors. Investing in new stable generation capacities and promoting energy efficiency (a cheaper alternative to building new generation capacities).