15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

03

October,

2015

Saturday,

03

October,

2015

Saturday,

03

October,

2015

Saturday,

03

October,

2015

"You mean there's a catch?"

"Sure there's a catch", Doc Daneeka replied. "Catch-22. Anyone who [claims he is crazy because he] wants to get out of combat duty isn't really crazy."

Joseph Heller, Catch 22

Пока гром не грянет, мужик не перекрестится.

Русская народная пословица

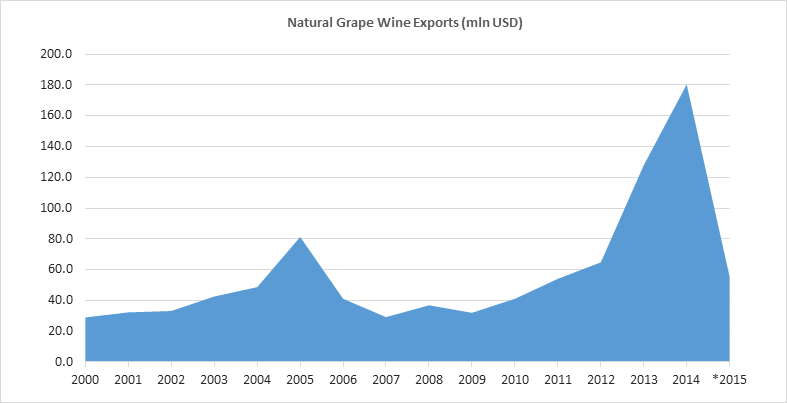

The Georgian wine industry had a couple of very good years in 2013 and 2014, following the opening of the Russian market. Exports skyrocketed, prices of grapes followed suit. For all the talk about diversification, within just two years, Russia’s share in the total exports of Georgian wine shot up from 0 to almost 68%.

Chart 1: Georgian wine exports by value (current USD)

The red grape varieties – providing the raw material for semi-sweet wines that are particularly popular on the Russian market – soared to hitherto unthinkable levels. For example, as exporters vied to place Stalin’s favorite Khvanchkara wine on the Russian supermarket shelf, the Alexandrouli grape variety, from which it is made, fetched a price of about 8 GEL per kg.

Needless to say, higher wine and grape prices provided powerful stimuli for additional investment in vineyards and processing capacity, putting even more eggs into the Russian basket. In just three years, grape production more than doubled from 144,000 tons in 2012 to about 290,000 tons in 2015 (expected harvest of this year).

With the Russian market sharply contracting in 2015, the amount of pain inflicted on the Georgian farmers and winemakers has been directly proportionate to the windfall gains they made in the previous two years. Grape prices fell to levels only slightly higher than prior to 2012. Saperavi, Georgia’s main red variety, is currently trading at roughly 82 tetri per kg, well less than half of the peak value (1.94GEL, on average) it achieved in 2014.

Kakhetian farmers are once again taking it to the streets, protesting over the prices offered to them by the wineries, and lobbying for higher government subsidies. And given that Georgia is entering an election year, they are likely to be successful.

The fact that overexposure to the CIS and Russian markets carried with it significant commercial risks for the Georgian wine industry was on everybody’s minds ever since the first shipment of Georgian wine crossed the Russian border in summer 2013. Initially, the main concern was that Georgia (and its wines) would once again fall out of favor with Russia, leading to the re-introduction of tariff and non-tariff restrictions on Georgian exports. But, even leaving politics aside, it was clear that having the entire industry depend on Russia subjected Georgia to the (uninsured) risk of a sudden downturn in that particular market.

Yet, despite these well-justified concerns, a paradoxical Catch 22 situation was created with the opening of the Russian market since most private actors in the value chain lost any incentives to invest in marketing their wines (and Georgia!) outside Russia and CIS. With every bottle of wine sucked into the Eurasian vacuum, they were busy celebrating and investing in additional grape growing and processing capacity. And, let’s face it, private Georgian wineries would have been crazy doing anything else since, taken alone, none of them have sufficient size to engage in the kind of massive international campaigning that would be required to introduce the fabulous story of Georgia’s winemaking to new markets.

While it is difficult to blame private companies for re-capturing the Russian market, perhaps the worst mistake was committed by the Georgian government, which failed to seize on the opportunity to prepare for the rainy day (which came sooner than anybody expected).

Table 1: Grape Prices and Subsidies, 2013-2015

| 2013 | 2014 | *2015 | |

| Average subsidy per kg (GEL) | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| Average price per kg (including subsidy) | 1.12 | 1.34 | 0.73 |

| Average share of subsidy in price (%) | 33% | 25% | 38% |

| Total volume processed (ton) | 89,849 | 117,861 | 92,653 |

| Total public funds spent (mln GEL) | 32.0 | 33.0 | 24.8 |

*as of 1 October 2015 (most of the grape harvest is finished). Source: Ministry of Agriculture and National Wine Agency

Thus, instead of engaging the private sector and coordinating a well-targeted marketing campaign (that could be financed by some of the windfall profits) to promote Georgian wines to new markets, the government spent tens of millions of lari on subsidizing the industry at a time when money was its least concern. As grape prices soared, the government slightly reduced the subsidy from 36 to 28 tetri per kg (on average). However, the total amount of taxpayers’ money thrown at wine producers and farmers (including, since 2013, not only smallholders but also large farmers cultivating more than 10ha) exceeded 30mln GEL in both 2013 and 2014.

What a waste!

While not representing a very large share in Georgia’s total exports (or GDP), the wine sector is of key significance for the livelihoods of the vast majority of Georgian farmers. At the same time, given how long it takes to go from grape seed to placing a bottle in a grocery cart, it is a sector that is extremely sensitive to changes in demand. Hence, the need for some sort of insurance.

Understandably, all governments in Georgia’s recent history were eager to provide price support and subsidize smallholder farmers in order to prevent a social and political crisis. Such a policy is equivalent to spreading the risks that are specific to winemaking over all the other sectors of the economy.

What the Georgian governments have failed to achieve thus far, however, is to properly insure the industry against extreme demand fluctuations which have been plaguing it since Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign of 1985-1988. Such insurance can only be achieved through greater diversification of Georgian wine exports, on the one hand, and promotion of new and traditional products such as organic and kosher wines, Chacha, brandies, and even Churchkhelas, on the other. Risks could also be reduced by investing in locally branded products and agritourism through a Japanese-style “one village-one-product” policy.

Finally, what about China? Almost a dozen small Chinese companies are currently trying to bring Georgian wine to China and the results are showing. Yet, the challenge these companies are facing can be summarized in one word: information. The average Chinese consumer is simply unaware of a country called Georgia, let alone its being at the origin of the world’s wine history. As we have learned through interviews, one or two containers of Georgian wine may take a year to distribute (through friends and relatives) as large Chinese wholesalers would rarely take upon themselves the risk of placing a relatively unknown product.

The Georgian government has recently established an office in Beijing to promote Georgia’s brand as a country. Such investment in international marketing is, of course, a great step forward, but many more (smart) steps would be needed. The government has 58 embassies (all of them in potential wine markets) across the globe. Mikho the wine-maker from Kakheti does not have a single embassy. It would therefore be highly beneficial for the government to take some of the money wasted on subsidies and, instead, make use of its diplomatic infrastructure to promote Georgian wine-makers around the world. (Incidentally, in this way, the government will also buy its own image insurance against regular farmer protests in Kakheti.)

* * *

The article was produced with the assistance of the European Union through its European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, CARE Austria, or CARE International in the Caucasus.