31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Wednesday,

16

March,

2022

Wednesday,

16

March,

2022

Wednesday,

16

March,

2022

Wednesday,

16

March,

2022

During such challenging times, as the Russia-Ukraine conflict escalates daily and threatens the lives of thousands, as well as the wellbeing of everyone around the world, having experienced the horror of war, we Georgians especially feel the pain of the Ukrainians.

While we strongly support Ukraine and are aware that the most essential outcome from all of these is a ceasefire and achieving the independence of Ukraine, in a world of interdependent economies, we also fear not only the potential escalation of the conflict to our country but also various economic threats derived from a dependence on the Russian economy.

Over the last few days, I have come across a broad debate around the political standing of Georgia in this conflict and its economic motivation. Many of these arguments have centered around the importance of the Russian cereal market and remittances. However, there was only a limited discussion on the consequences to Georgia’s energy markets, despite the crisis on the energy market has played a crucial role in the political decisions of much larger and more developed countries.

Energy products enter both directly and indirectly into our consumption basket and thus affect our living standards. On a daily basis, we receive critical energy services for heating, cooling, lighting, cooking, and transportation. Moreover, we consume goods produced either in Georgian factories using electricity as a production factor or those transported from other countries necessitating vehicles fueled by diesel and petroleum. Thus, any shift in energy and delivery prices are reflected twofold in consumers’ baskets; through both direct communal costs and indirect variations in the cost of production, transportation, and logistics, as reflected in higher goods prices.

The current conflict has undeniably revealed the potentially dramatic consequences of reliance on Russian energy products, even within an integrated and highly developed market like that of the EU. Therefore, to prevent avoidable shocks and respond to the crisis in a gradual and effective manner, while also limiting the quality of life economic impacts, it is of the utmost importance that the Georgian public and government are fully aware of what is at stake and to act accordingly.

When assessing our dependence on Russian energy, we should look closely at the electricity, gas, and oil markets, as well as their development paths. This becomes important as Georgia’s future energy security depends, crucially, on its ability to satisfy steadily increasing energy demands (for electricity, oil products, and gas), through a diversified portfolio of energy suppliers. Without any policy changes, the risk of reverting to substantial energy dependence on Russia rises alongside energy demand.

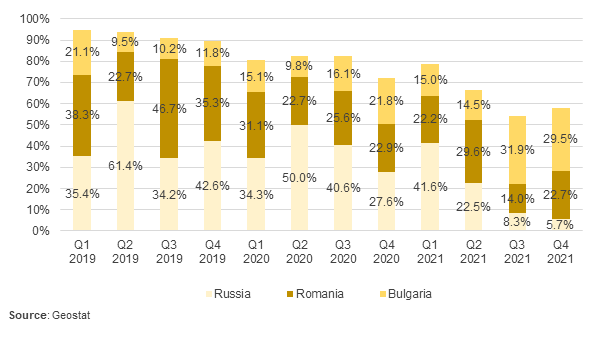

Since the electricity and gas markets are characterized by seasonality, to recognize any dependence on the Russian market during the most energy-scarce periods, we have represented the Georgian quarterly import data for electricity, gas, and oil products over the last three years (2019 -2021).

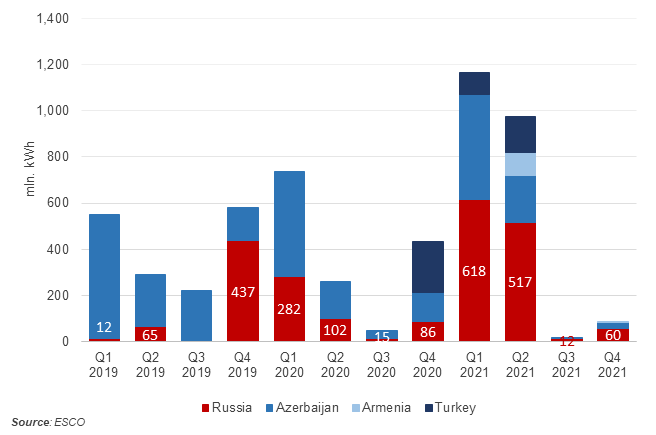

Looking to the electricity market (Figure 1), starting from 2021, Russian imports rose substantially due to increased demand from Abkhazia and the rehabilitation shutdown of the Enguri HPP.

Figure 1. Georgian imports between Q1 2019-Q4 2021

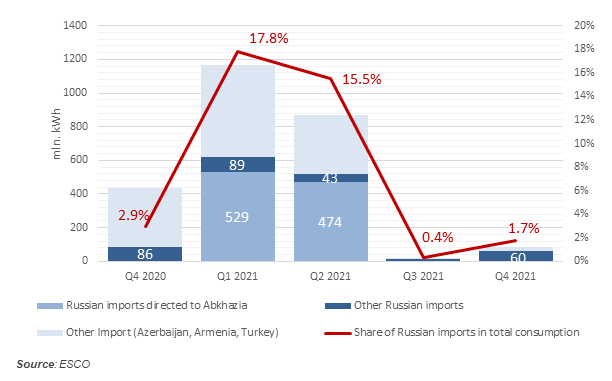

The portion of Russian imports may appear substantial at first glance, nevertheless compared to total consumption the shares are negligible. For example, in Q1 2021, when the country’s dependence on imported electricity was at its highest, the share of total Russian imports in all consumption was 17.8%. These numbers are even lower (2.6%) if we exclude Abkhazian demand. Within this framework, Georgia appears not to be substantially dependent on Russian electricity imports. Nonetheless, the challenges with Abkhazian electricity consumption remain unsolved, reflecting a sensitivity towards issues of Russian occupation. Despite the Abkhazian claim to 40% of Enguri HPP production, in the past, they have consumed 100% and sometimes more so from the Georgian electric system.

Figure 2. Russian electricity imports and their share in total electricity consumption (mln. kWh). Q4 2020-Q4 2021

Yet another concern derives from the electricity market’s interdependence with the gas market. The Georgian electricity system uses Thermal Power Plants (TPPs), which are particularly intensive in the winter season, and use imported gas for electricity generation. However, from discussing the issue with representatives from the Georgian National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission (GNERC), it seems that TPPs typically operate on Azerbaijanian gas. Therefore, in the short term, concerns about dependence on Russian gas in the electricity generation sector are limited. These concerns do however remain because reliance on a single gas provider is hardly the best option to ensure security in the sector.

All in all, we can claim not to be critically resource dependent on the Russian market, although, regarding electricity security, we should not forget the linkages between the Georgian and the Russian grids. We should be cautious and remember that the technical functioning of the Georgian grid, and its stability, have been contingent on Russia since the Soviet period. This highlights a need for timely precautionary measures to decouple the Georgian and the Russian networks and to minimize any potential economic and social consequences in the event of disparities between Georgia and Russia. Until the conflict, Ukraine had this very issue, although it had been trying to disengage from Russia and to connect to the West European grid for some time. We saw how Ukraine had to operate in an “island mode” for almost three consecutive weeks before its power system was fully synchronized with the power grid of Continental Europe (ENTSO-E) on March 16.

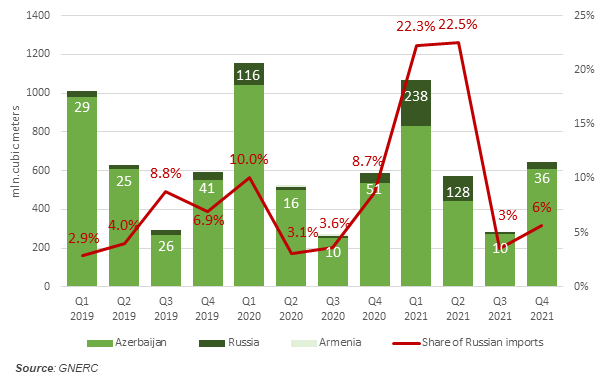

Even excluding the gas necessary for TPPs, a portion of the gas market still relies on Russian imports. In 2019 and 2020, the share of the Russian supply from the total gas demand varied from 2.9% to a maximum of 10%. The Russian gas share, however, substantially increased in the first two quarters of 2021; amounting to 22.3% and 22.5% of the total Georgian gas supply, while again decreased in the last two quarters of the year (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Natural gas imports by country

We cannot confidently claim an increasing trend of gas imports from Russia. Nevertheless, observing the Georgian gas imports in 2021, we have discerned on average a bit higher share of Russia in the total imports compared to previous years.

Even though the oil market is less concentrated than either the electricity or gas import markets, and it is more easily diversified, Russia continues to play an important role as a supplier on this market as well.

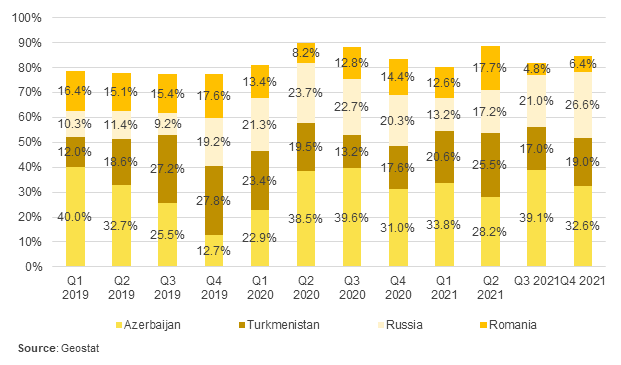

Georgia has imported diesel from approximately 40 countries over the last three years. Within this period, Russia remained one of the four major suppliers. From Figure 4, Russia here has equally maintained a somewhat moderate share (in the range of 9%-27% over the last three years), however, this trend does appear to be increasing.

Figure 4. Diesel imports – top 4 country shares

Regarding petroleum products, Georgia has up to 17 partners, one can see that Russia held a persistently high share in the total imports in 2019 and 2020, though this declined dramatically in 2021 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Petroleum imports – top 3 country shares

When observing the oil markets, the Russian stake is also moderate although the possibility for diversification is greater.

RUSSIAN CAPITAL WITHIN GEORGIAN ENERGY BUSINESSES

Unfortunately, our energy dependence does not only derive from the trade sector. According to a 2015 IDFI report reviewing Russian capital in Georgia, Russian businesses possess a substantial share in key and strategically important entities in the Georgian energy stock market. A look at the latest currently available information also confirms the significance of Russia’s presence on the Georgian electricity market today.

For example, 70% of JSC Telasi stocks, a major Georgian network company that carries out the distribution and sale of electricity in Tbilisi, is owned by a Russian company, Inter Rao UES JSC. Telasi, among others, also owns two large regulatory HPPs – Khrami 1 and Khrami 2 – the generation of which represented 5% of total local consumption in 2021.

Another similar example is UES SAKRUSENERGO, which holds and operates several strategically important 500kV, 330kV, and 220kV transmission lines, 50% of which are owned by JSC Russian United Energy System (РАО “ЕЭС Россия”).

Even if we neglect such strong players as Lukoil on the oil market, the ownership of some small HPPs and the significant possibility of greater energy sector investments from Russia in the latter years these two examples alone reveal the potential market power of Russian investors on the energy sector.

When considering sanctioning Russian operations and products on the Georgian market as a response to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, we should certainly be conscious of the potential economic implications. Crucially, sanctioning the owners of key transmission lines or distributor companies on the electricity market could drive higher tariffs through increased transmission and final supply costs.

The Georgian energy sector still depends on Russia for several features – mostly related to geographic proximity and historical factors. We should therefore be mindful that Russian businesses own some key assets of the Georgian energy infrastructure. Even though the scale of dependence is not a cause for alarm in the short term, Russia is consistently among our major partners in all key energy products, many of which define our quality of life and enter our everyday consumption basket. Reducing the dependence on Russia calls for an acceleration in policies aimed at increasing energy security, requiring additional investments and Georgia taking potentially uncomfortable steps – especially at the beginning. What these steps may be, and the potential alternatives, are questions we intend to ask and answer in an upcoming blog. For now, being aware of the current situation, and acknowledging what could be at stake, is already a good start.