31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

22

November,

2021

Monday,

22

November,

2021

Monday,

22

November,

2021

Monday,

22

November,

2021

The International Energy Agency provides a definition of energy security across two dimensions. In a broad sense, energy security is defined as the “uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price,” while short-term energy security denotes that an energy system has the capability to promptly balance any disruption in the supply-demand equilibrium.

Energy security is hardly a standalone subject for nations, as it may also play a core role in international relations (Yergin, 2006). Moreover, energy security is multidimensional and is not limited to any single form of energy. Throughout history, there have been different forms of energy deficits, associated with a shortage of oil, natural gas, or electricity, or with interruption of supply due to geopolitical tensions. Therefore, the availability of supply from different types of energy sources and unique providers are extremely important when ensuring energy security for a country.

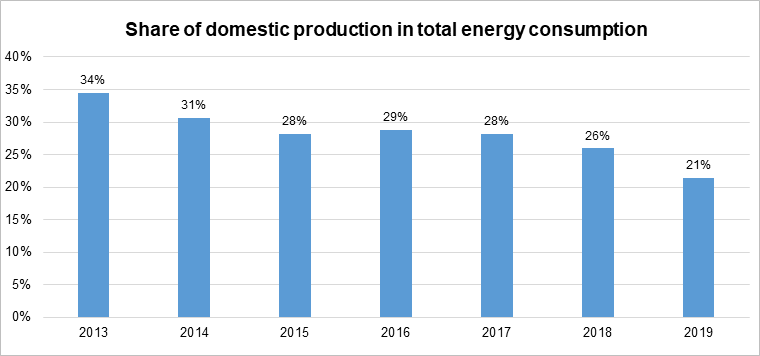

To see how Georgia’s energy security has been evolving over time, one must start by looking at the patterns characterizing total energy consumption and domestic production. The import of energy is also an important indicator as it highlights the level of dependence on foreign energy sources. When analyzing Georgian energy balances from 2013 to 2019, a clear downward trend in total domestic production is observable, whereas consumption steadily increased as time progressed. As a result, from total energy consumption, the share of domestic production decreased from 34 percent in 2013 to 21 percent by 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of domestic production in total energy consumption

The decrease in domestic production mostly relates to a decline in two energy sources: coal, and biofuel and waste, which sank by 96 percent and 49 percent over the six-year period, respectively. The main increase in consumption was found in the natural gas category, which rose by over 50 percent within the same time frame (National Statistics Office of Georgia, 2014-2020). This is in great part due to increased access to natural gas around the country. According to the Georgian Gas and Transportation Company, starting from 2013, more than 1000 populated areas have been involved in the gasification program. Under the plan, 90 percent of the Georgian population will have access to natural gas by the end of 2021. As gas is increasingly available for the public, more and more families are shifting from traditional energy sources (coal and biofuels) to natural gas. However, there is almost no domestic production of natural gas in Georgia, this, therefore, translates to a growing proportion of imports on the Georgian energy balance.

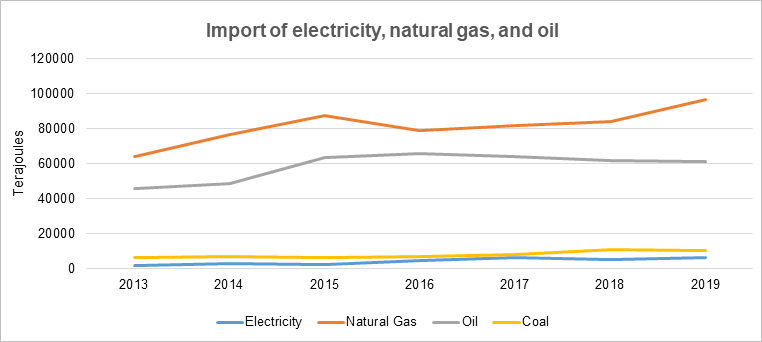

In the 2019 energy balance, the four main imported energy sources were oil and oil products, natural gas, electricity, and coal. Figure 2 presents the evolution of imports for these energy sources from 2013 to 2019. It is interesting to observe how, despite the characterizing discussions on the development of the electricity market and the existence of an increasing electricity generation-consumption gap, the contribution of the electricity gap to the overall Georgian energy deficit is extremely small. Coal imports are hardly greater than the import of electricity (in terms of terajoules), thus its import also makes up just a modest share of the total energy import. On the other hand, the import levels of natural gas and oil are significant due to the fact that domestic production is almost zero. It is also noteworthy that natural gas imports rise most years, while oil imports have been relatively stable since 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. import of electricity, natural gas, and oil

Due to structural transformation and modernization of its energy sector, Georgia has naturally shifted towards foreign energy sources, as such, it has become invaluable to analyze the import patterns of different energy sources in greater detail and to consider their potential impact on the energy security of the country. Although energy independence sounds unrealistic in the short, or even medium, term (due to the simple fact that Georgia has no oil or gas fields), the country should, at least, try to diversify its trade partners, as this remains the key to energy security (Yergin, 2006).

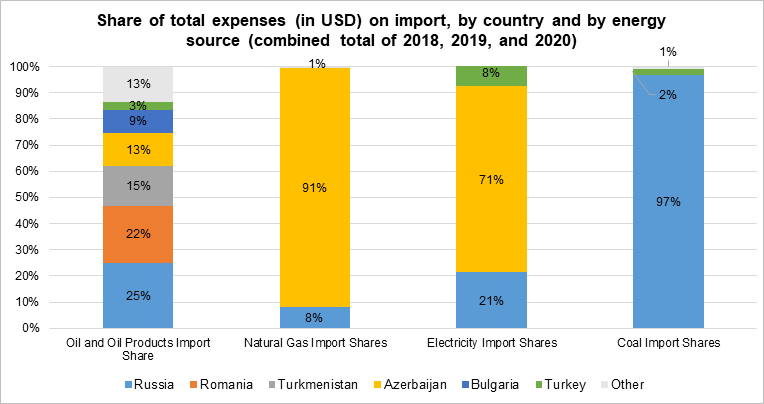

There is currently not a sufficient stock of crude oil to satisfy domestic demand. Therefore, Georgia expends a significant amount of money on oil and oil products. For instance, in 2018, Georgia spent 864 mln. USD on oil and oil products imports. A substantial part of which went towards imports from Russia, Romania, Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan – 23 percent, 22 percent, 17.5 percent, and 12.7 percent, respectively. In the following years, the total expenditure on these products declined significantly – in 2020, the expense dropped by 42.3% compared to 2018. The main reason being, understandably, the pandemic; under restrictive conditions (curfews, flight cancellations), the demand for oil products, including fuel, for domestic consumption declined. However, the main import countries for petroleum remained the same. Overall, the import market for oil and oil products is fairly diversified: Georgia imports from 61 different countries; with six (Russia, Romania, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, and Turkey) holding an 87 percent share of the total expense (Figure 3).

According to Geostat, in 2018 approximately 281 mln. USD was spent on natural gas imports. Most of these (amounting to 96.4 percent of Georgian spending on gas import) came from Azerbaijan. While a small portion (2.8 percent) of these costs went towards natural gas from Russia. This trend changed a little over the following years as dependency on Azerbaijani gas started to decrease. Nevertheless, Georgia remains highly dependent on this supply. In 2020, the total expense on natural gas imports equated to 302 mln. USD, only 4 percent lower than in 2019 and 7.5 percent higher than 2018. Therefore, the pandemic does not seem to have had a major impact on natural gas imports. Overall in 2020, 91 percent of these expenses fell on imports from Azerbaijan, while imports from Russia and Armenia amounted to 9 percent of the total spending on natural gas (Figure 3). Over the last six years, on average, around 25 percent of imported natural gas has been used in the transformation sector (where thermal power plants transform it into electricity).

Within these last six years, Georgia has satisfied around 12 percent of its electricity needs using electricity derived from neighboring countries. Although the imports of coal are larger than those of electricity (in terajoules), the total expense on electricity has been significantly higher. In 2018, Georgia spent approximately 75.4 mln. USD on electricity imports, and by the following year this number had grown by 4 percent. Due to the impact of the pandemic, imports declined by 17.6 percent in 2020, where the total electricity bill amounted to 65 mln USD. A significant part of these electricity imports was derived from Azerbaijan. For instance, 84.2 percent of the total costs behind imported electricity in 2018 went towards the Azerbaijani supply. In the following years, dependency on Azerbaijani electricity fell and a portion came from Russia and Turkey. By 2020, 56.4 percent of the electricity expenses were spent on Azerbaijani electricity, 22.6 percent on Russian, and 21 percent on Turkish supplies. Overall, within these three years, 71 percent of the import cost came from Azerbaijan, while expenses on imports from Russia and Turkey comprised 21 percent and 7 percent, respectively (Figure 3). It is important to note that the data on the direct import cost of electricity underestimates the true burden associated with electricity demand. This is due to the fact that thermal power plants use gas to generate electricity. Around one-fourth of total natural gas, imports are used in thermal power generation, therefore the true costs of satisfying the country’s electricity needs are substantially higher than suggested by the raw data.

The main import market for coal is Russia, with around 97 percent of all such costs in the period from 2018 to 2020 spent on the Russian supply. Only 2 percent of expenses fall on Turkey, while the other eight countries providing coal to Georgia comprise only 1 percent of the total costs (Figure 3). On average, a total of 22 mln. USD has been spent annually on coal imports over the last three years.

Figure 3. Share of total expenses (in USD) on import, by country and by energy source (combined total of 2018, 2019, and 2020)

As Georgian energy demand turns towards foreign sources, the share of total energy consumption covered by domestic production is shrinking. Given the increased demand for “modern” energy sources and the limited domestic endowment of fossil fuels, the main approach for Georgia to reduce its energy dependence and lessen the burden of imports is to harness the country’s potential for electricity generation. As of today, local renewable energy sources provide the largest domestic supply of electricity, satisfying around one-sixth of total Georgian energy demand; hydropower presently represents the key source of energy, although solar and wind power is expected to expand in the future. According to MOESD estimates, the new (renewable) installed capacity between now and 2030 will amount to almost 50% of the total capacity existing today. Even this, however, would not be sufficient to help the country reach the same share of domestic production in total energy consumption as in 2013. Taking 2019 as a reference point, Georgia would need to have generated 84 percent more electricity (be it from hydro, wind, geothermal, etc.) to maintain the same share of domestically generated energy as in 2013. While the less ambitious goal of replacing natural gas imports for electricity generation would still require a 30 percent increase in the electricity generated by renewables. Therefore, it is no surprise that Georgian policymakers are trying to expand domestic electricity generation (most notably hydropower).

In conclusion, there is an increasing gap between energy demand and the country’s capacity to satisfy it, and it is still necessary to ensure that the Georgian public remains well-informed about the dynamics of the energy sector. The short-term method of closing this gap is to import energy from abroad. Currently, however imports of electricity, natural gas, and coal are not diversified, and these sectors depend largely on a supply from Azerbaijan and Russia. The picture in the oil and oil product market is somewhat different. In this case, there are numerous choices, and no country holds more than a quarter of the share of Georgian imports. The general tendency shows us that, while the demand for traditional – and domestic – energy sources is fading, the transition to other energy sources is making Georgia more dependent on foreign supply. In this context, expanding the country’s renewable energy generation is essential not only for closing the – currently small – electricity consumption-generation gap, but much more importantly, to reduce the energy gap, and thus make the country more energy secure.

National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2014-2020). Energy Balance of Georgia.

Yergin, D. (2006). Ensuring Energy Security. Foreign Affairs, 69-82.