15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

08

March,

2021

Monday,

08

March,

2021

On February 15th 2021, export quotas on wheat, rye, maize, and barley entered into force in Russia. Russia also imposed customs tariffs and prohibitive duties amounting to 50% of customs value on these products.

In general, the introduction of customs tariffs or quotas on exports is a part of a protectionist policy and is, more often than not, directed towards the protection of local producers and markets. Export quotas entail restrictions on the number of specific goods and services within an outlined period of time with the aim of maintaining low prices on respective goods for local consumers. Unlike quotas, customs tariffs are imposed as a means of generating state revenue, which may subsequently be spent on strengthening local producers. Traditionally, imposing export restrictions translates into growth of local supply and price reduction in exporter states, which is mirrored by an increase in prices of imports and a decrease in demand from importer states. In theory, there are two central factors for this effect:

It is also worth noting that an increase in import prices may support the growth of local production in importer states.

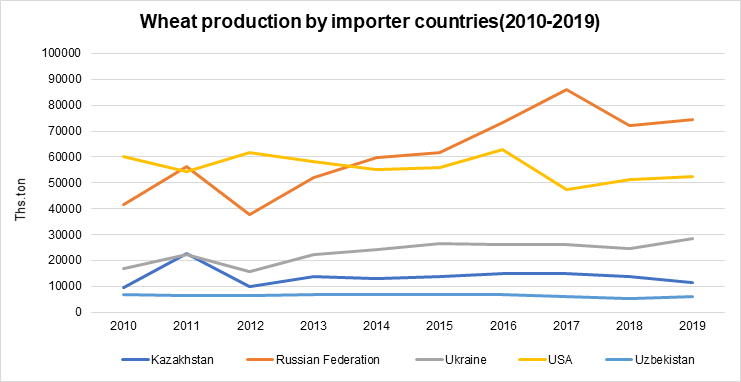

According to data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), in 2019 China was the biggest producer of wheat with a 17% share of global production followed by India (14%), Russia (10%), the US (7%), and France (5%). Georgia imports most of its wheat from Russia. In 2020, 95% of total wheat imports came from Russia, with 4% imported from the US. In the period of 2012-2015 Georgia imported large quantities of wheat from Kazakhstan and Ukraine, however, Russian wheat quickly replaced these markets (Geostat, 2021), which is not surprising, as Russia outperforms Georgia's other trading partners in terms of wheat production (Table 1).

Figure 1. Wheat production in importer countries (2010-2019)

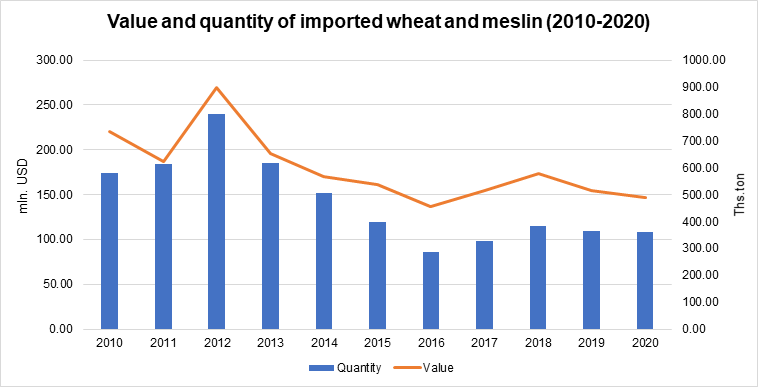

It is significant that, in general, both quantity and prices of imported wheat were characterised by a downward trend in the period of 2010-2020 (Table 2), which can be explained by increased local production and, thus, a rise in self-sufficiency coefficient (2010 – 6% and 2019 – 15%) (Geostat, 2021).

Figure 2. Quantity and value of imported wheat and meslin, 2010-2020

Wheat import prices (HS1001), which fluctuated from $190-280 per tonne in the period of 2012-2020, show a downward trend. During the last two years the price reached its minimum and amounted to $213 and $219 per tonne in 2019 and 2020 respectively. Import prices of hard wheat are relatively higher (except for wheat seeds, HS100119), reaching $226 and $252 per tonne in 2019 and 2020 respectively (Trade Map, 2021).

A review of wheat trading statistics revealed that Georgia is dependent on the Russian market, with a low level of market diversification. Therefore, the imposition of trade restrictions by Russia may result in a rise in the prices of bread and pastry in Georgia. In order to avoid such outcomes, the Government of Georgia took the following measures:

According to the Association of Wheat and Flour Producers, due to the import restrictions, the Association has increased its storage of wheat, for the time being maintaining bread prices with the support of the subsidy programme. However, due to the aforementioned restrictions, an increase in wheat prices is expected. The increase in input prices will, thus, be reflected in an increase in bread prices. It should be noted that bread producers in Georgia plan to increase bread prices starting from April. They state that the price of bread is likely to increase due to higher prices on petrol and yeast, as well as increased electricity tariffs.

In order to maintain bread prices, it is recommended to:

The Ukrainian market is of no less significance. Ukraine produces more wheat than Kazakhstan. Additionally, during the recent decades, both production and exports of Ukrainian wheat are characterised by an upward trend. For both Russia and Ukraine, the main export markets include Egypt, Bangladesh, and Turkey, with the Georgian market taking a minor position among Ukraine’s wheat export markets. It is important to better research the Ukrainian market and cooperate with both state and private sector representatives in Ukraine.