10

July

2023

10

July

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

03

December,

2016

Saturday,

03

December,

2016

Saturday,

03

December,

2016

Saturday,

03

December,

2016

My dad used to tell me stories about the exciting period when the Soviet Union’s economy started faltering and public resources were suddenly up for grabs in the chaos of capitalism that emerged. While this period is usually associated with the appearance of crafty oligarchs, in Georgia also less wily businessmen could exploit the circumstances, among them many Turks.

As the American journal, The Tennessean wrote in 1977: “Soviet blue jeans may look like jeans, but that doesn't mean they are… One of the country's most exasperating problems is trying to satisfy the Russian hunger for jeans.” In the late 1980s, my father observed how Turkish traders made fortunes by bringing jeans, women’s bras, and other chintzy clothes to Georgia and exchanging them for precious metals and other valuables. A bit later, when the Soviet economy had entirely collapsed, the infamous asset-strippers entered the scene: whole factories were dismantled and exported as scrap metals for a penny on the dollar. Many of these “exports” went to Turkey, which was geographically the most natural destination. In turn, the Turks sold their textile products in Georgia, as Western apparel was considered a highly prestigious and therefore desired commodity by Soviet and post-Soviet consumers. As a result, the Turkish textile industry experienced a boom, having its heyday around the turn of the millennium.

But no party lasts forever…

From an economic perspective, having a strong textile industry is a double-edged sword due to its heavy dependency on low labor costs, particularly when it comes to the most labor-intensive CMT activities (cut, make and trim). A country will have a textile industry only so long as it offers the cheapest labor. Once economic development sets in, textile producers will be the first to leave. Turkey was not an exception to this general rule. Between 2000 and 2010, the apparel and textile industry were among the largest and best-performing sectors of the Turkish economy. By 2009, the country operated 56,000 apparel and textile companies which employed around two million people. The industry’s exports accounted for 18.69% of Turkey's total exports (CIA World Factbook, IMF World Economic Outlook, 2009).

Yet, between 2009 and 2013, Turkish salaries almost doubled, leading to the country’s loss of its cost advantage. The creeping demise of Turkey’s textile industry became already visible in 2005 when the World Trade Organization eliminated all quotas in textile trading between its member nations: a competitive industry would have benefited from such a development, yet the Turkish textile industry lost market share, demonstrating its vulnerability.

A similar development could be observed on a much larger scale following the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Textile production was at the heart of industrialization, and except the steam engine, most other important inventions of that period related to clothes, like the Spinning Jenny, the Spinning Mule, and the Roberts Loom. Yet, already in the 19th century, textile production in Europe had come under enormous pressure, leading to hardship among those employed in the sector, as described in the verses of Heinrich Heine’s poem The Silesian Weavers (published in Karl Marx’s Vorwärts! newspaper in 1844): “Their gloom-enveloped eyes are tearless, They sit at the spinning wheel, snarling cheerless… A curse on God to whom we knelt when hunger and winter cold we felt… A curse on the king, The wealthy men's chief Who was not moved by our grief, Who wrenched the last coin from our hand of need, And shot us, screaming like dogs in the street!" (translation by Sasha Foreman).

The agony of the European textile industry came to an end in the aftermath of the Second World War, and today there are virtually no textile producers anymore in Europe.

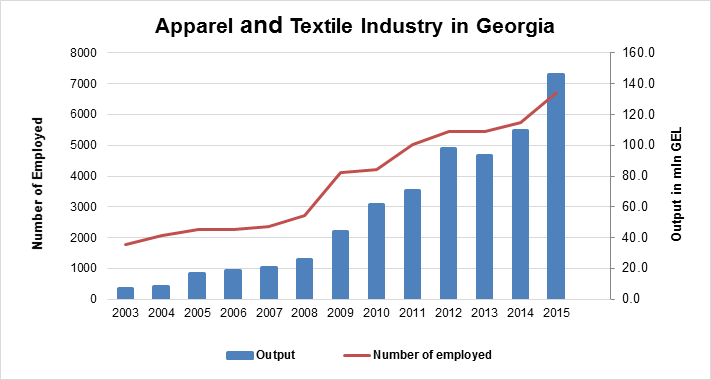

Offering cheaper labor to neighboring Turkey, Georgia’s Adjara region became the natural destination of the wandering textile industry in recent years. As the diagram shows, starting in the mid-2000s, the Georgian textile and apparel industry has experienced an upsurge, both in terms of output and the number of employed. This positive development has become particularly visible by 2015 when Turkey eventually lost its cost advantage.

The situation is likely to remain bright for Georgian textile producers in future years. Until recently, Georgia’s DCFTA agreement with the EU did not allow us to export apparel and textiles tariff-free, as the raw materials used in the production were mostly of Turkish origin. In October 2016, however, an agreement was concluded, allowing what is called in trade lingo “diagonal cumulation”. As a result, Georgia can now start exporting textile products to Europe labeled as Made in Georgia despite having Turkish inputs.

Not surprisingly, investors promptly reacted to this news! On November 2, 2016, Turkey’s ENA Textile, a sub-contractor of the world-renowned brand ZARA, announced its decision to build a clothing factory in the small town of Ozurgeti in Western Georgia. The factory will employ around 1,000 persons (to be trained at the “Horizonti” VET college), a huge number for a small town with about 15,000 inhabitants. Two days later, other leading Turkish brands, Penti and Dagi, started discussions about the construction of clothing factories in Kutaisi.

What will Georgia do when the errant textile production moves on? For Turkey, the ‘destruction’ of its textile industry turned out to be at least somewhat ‘creative’, as some textile manufacturers managed to move up the value chain by upgrading their production capabilities and moving from the low-margin cut-make-and-trim (CMT) activities into fashion design, successfully introducing new styles and quality labels, targeting high-end customers.

Much of the growing global profile of Turkish fashion is thanks to government initiatives such as Turquality. As described by the Turkish Culture Magazine, this campaign was launched in 2005 to promote “the designs of key brands, including Sarar, Colin’s, Damat Tween, İpekyol, Koton, Machka, and Mavi – around the world. Further programmes from the Istanbul Textile and Apparel Exporter Associations (ITKIB) and the high-profile Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Istanbul are also demonstrating Turkey’s burgeoning style credentials.”

Georgia could and should follow Turkey’s example. After years of strife for international recognition, Georgians start proving that there is fashion talent in this country. For example, in 2015, a Georgia-born designer Demna Gvasalia was appointed to the position of Creative Director at the Paris-based Balenciaga, one of the world’s foremost fashion houses. Importantly, Gvasalia is but a symbol of a large movement. While in the past, one could count successful Georgian designers on the fingers of one hand, it has now become difficult to keep track of all the new names!

Rather than wait for the CMT industry to move on (or become robotized), the Georgian government could use the current momentum to launch a “Designed in Georgia” branding campaign and in this way channel Georgians’ innate creativity into the lucrative fashion design and clothing industry.