10

July

2023

10

July

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

11

March,

2017

Saturday,

11

March,

2017

Saturday,

11

March,

2017

Saturday,

11

March,

2017

In the last few decades, large supermarkets (referring to all modern retail, which includes chain stores of various formats such as hypermarkets, convenience and neighborhood stores) have changed the retail business landscape in many countries through larger store formats, more shelf space, an increased variety of goods and services, and extensive marketing strategies. The so-called “supermarket revolution” has been underway in developing countries since the early 1990s, and supermarkets have now gone well beyond their initial upper and middle-class customers in many countries to reach the mass market.

Although urbanization and increased incomes have played an important role in the rise of supermarkets, other factors have also made a significant contribution. One of the most crucial factors has been the liberalization of foreign direct investments. Moreover, intense competition, consolidation, and multi-nationalization in the supermarket sector have also accelerated the spread of supermarket chains that are seeking to improve their competitive positioning.

The impact of the growing number of supermarkets on a country’s economy may have two distinct effects. On the one hand, increased competition from modern retailers decreases revenue for traditional shopkeepers, and may even force them out of business. On the other hand, modern retailers create new employment opportunities and can bring about positive spillover effects (e.g. increased variety and increased labeling to imitate the supply offered by the modern retailer).

Above and beyond this, a fast-growing trend by supermarkets has diverse impacts on consumers and their behavior. Supermarkets are able to charge consumers lower prices and offer more diverse products and higher quality than small groceries. These advantages allow them to spread quickly and take control over a large share of the consumer market. The food price savings (because of lower prices) accrue first to the middle class, but as supermarkets spread into the food markets of the urban poor and into rural towns, they have positive food security impacts on poor consumers.

When supermarkets spread and their market share grows, small groceries’ market share may decline. Evidence of the impact of large supermarkets on small grocery stores is mixed. For instance, Sobel and Dean (2008) studied the impact of Wal-Mart’s (an American multinational retailing corporation that operates as a chain of hypermarkets, discount department stores, and grocery stores) entry on small retailers, and demonstrated that there was no long-term effect on the overall size and growth of U.S. small business activity. On the other hand, Jia (2008) showed that the entry of Wal-Mart alone explains 37% to 55% of the net change in small retailers in small and medium-sized US states. Furthermore, Basker (2005) estimates that in the year of Wal-Mart's entry into the market, retail employment in a county increases by 100 jobs. Half of this gain disappears over the next five years, like other retail establishments exit and contract, leaving a long-run statistically significant net gain of 50 jobs.

A study by EBRD (2011), “Social impact of Discount Food Retail in Remote Regions – Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania (2011),” analyzes the impact of large supermarkets in an environment similar to Georgia’s. Through quantitative and qualitative analysis, the authors point to evidence that the emergence of modern retailers has a negative impact on the survival of traditional shops: gross receipts of smaller shops decline, and the number of people employed follows the same trend over time. On the other hand, the study also showed that job creation by modern retailers exceeds job destruction of traditional shops, leading to a positive net employment impact. Moreover, a shift from self-employment to wage employment was observed.

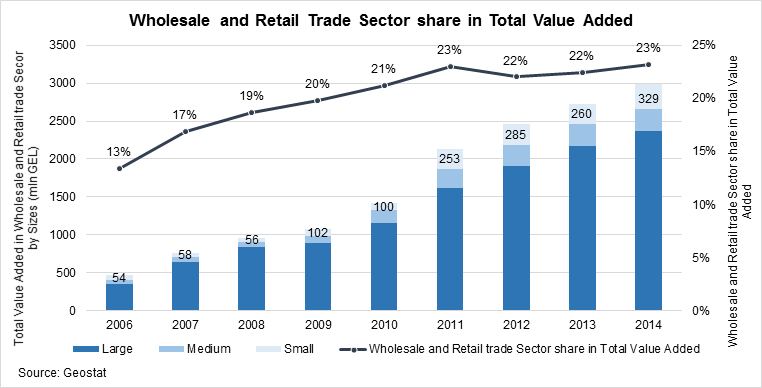

Wholesale and retail trade is one of the largest sectors in the Georgian economy, providing 23% of the country’s total value added in 2014. The sector has been increasing fast and steadily since 2006, with large-size enterprises contributing the bulk of this increase. Value added by small and medium size-enterprises, on the other hand, has been lagging behind, especially since 2011.

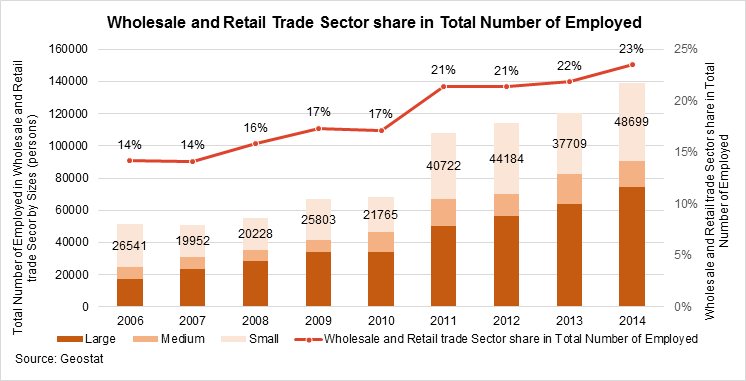

Just like value-added to this sector, employment in the sector has also been on the rise since 2006, with wholesale and retail trade formally employing around 23% of the total employed in the business sector. Unlike the value-added, the share of small and medium-size enterprises in total employment in the sector is higher than that of large enterprises. Taking into account the shadow economy, the actual impact of the sector is possibly much larger, particularly so in small and medium scale retail activities, where informality is much more common and widespread. Putting these figures together, one may easily detect very low sector productivity, particularly in the small-sized enterprises, but the social security role they play should not be neglected either.

In addition to employment, locally owned small businesses contribute significantly to a country’s economic stability compared to their absentee-owned counterparts. Small locally owned businesses (among them local groceries) help boost local economic activity. In other words, they create the foundation for local income, wealth, and stable jobs.

Moreover, locally-owned traditional retailers rarely move, and their owners are not inclined to relocate to other places (internationally) to get a higher rate of return from their businesses. This means that they are much more reliable generators of wealth, income, and jobs. Thus, the comings and goings of large (nonlocal) retailers create significant stresses on small communities’ (little retailers) economy. Therefore, local retailers are essentially an insurance policy against these stressors. In addition, in many developing settings, small retailers still provide additional food security “service” for vulnerable groups by trading on credit, which large supermarket chains claim they “cannot afford.”

Since 2000, many international and local supermarkets began to expand their affiliates and increase their market share in Georgia. According to Colliers' 2015 Retail Market Report, hypermarkets and supermarkets occupy 25% of modern shopping centers and 11% of street retail floor space. Among the core representatives of this category are international and regional brands (Carrefour, Spar, and Furshet), as well as local supermarket chains (Goodwill, Smart, and Fresco). Smaller modern grocery chains, such as Ori Nabiji and Nikora, have also been growing aggressively in recent years.

The increasing number of large retailers creates problems for small grocery stores that are already operating on the market. The majority of small stores are not able to offer differentiated products in line with different types of sales. Thus, they lose consumers and are left with few resources to update and develop themselves in order to compete with large supermarkets.

In order to sustain the social and economic benefits that large retailers bring, policymakers might be inclined to implement some inclusive policy measures that would help small retailers gain competitiveness in the market. One option is to help them specialize in certain high-quality niche products, locate in non-congested areas, and/or upgrade human capital to provide better service. Even when it is challenging to differentiate themselves by the merchandise they carry, small retailers can still survive if they concentrate on building a closer relationship with local shoppers. Another option is to help upgrade the wholesale market infrastructure and value chains to maximize access by small retailers to a diverse set of traditional and niche products. However, one might argue that the market should freely decide by itself the rules of the market, and let the strong participants force out the weaker ones. If this were this case, resources could be allocated according to free-market rules, and in the long run, the economy would benefit from increased efficiency and lower prices. However, it is hard to judge which of these approaches would lead to a stable and inclusive social outcome in the long run.