15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

24

April,

2017

Monday,

24

April,

2017

Monday,

24

April,

2017

Monday,

24

April,

2017

The village of Chkhakaura is located en route to the famous Bakhmaro resort in the Gurian Mountains. This settlement is not only in a picturesque environment but also the home of hard-working people, some of whom we introduced in our success story about the agricultural cooperative “Samegobro 2014”. Since their registration as a formal cooperative back in 2014, this group of fish farmers is becoming increasingly successful. The cooperative is well-linked to local markets, both with regards to purchasing equipment and inputs (a “backward” linkage), as well as with restaurants, hotels, wholesalers, or local customers (a “forward” linkage).

As illustrated in a short documentary, the ENPARD-financed cooperative “Samegobro 2014” is both contributing to and benefiting from local market development as a result of forming their cooperative. The cooperative members started to become known by other actors of the value chain and form persistent links with them. As one member of the cooperative, Otar Giorgadze mentioned: “No one knew me....now, they know us, and the cooperative looks more reliable”. Today, the cooperative is regularly selling trout to one of the most popular supermarket chains in Kutaisi, “Gurmani”. The well-established connections are one of the crucial factors as to why the “Samegobro 2014” cooperative became a sustainable business model.

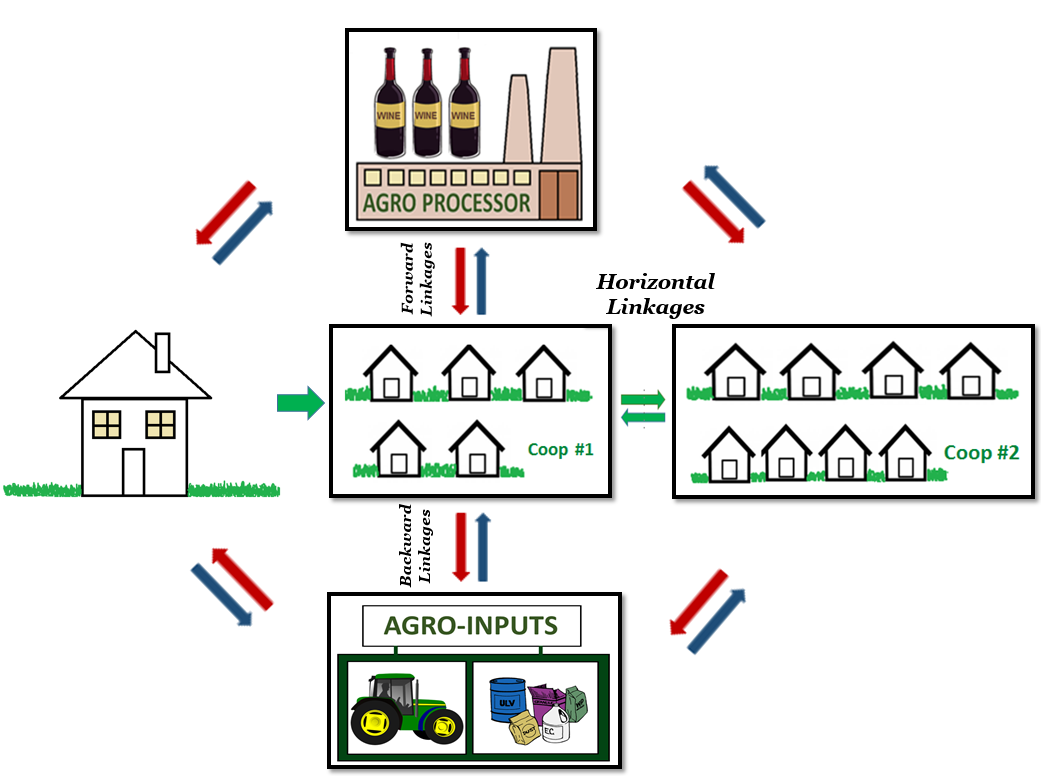

Decades ago, the economist Albert O. Hirschman highlighted the importance of linkage effects in encouraging economic growth. Modern agricultural value chains are increasingly characterized by well-developed horizontal and vertical linkages. Farm cooperatives are a good example of horizontal linkages formed between actors at the same level of a chain. Vertical linkages, in comparison, are formed between actors at different levels of a value chain (e.g., between farmer and processor). The literature distinguishes between two types of vertical linkages – the backward and forward linkages. A backward linkage is developed when there is a new demand for intermediate inputs for the production of final outputs. For instance, when an agricultural cooperative is producing strawberries in a greenhouse, members of the cooperative may procure greenhouse construction materials, drip irrigation, seedlings, or fertilizers. This further catalyzes the development of these input markets, hopefully leading input suppliers to achieve greater economies of scale in production or distribution, thereby lowering costs (lowering production cost which in turn might reduce input expenditure for farmers). A forward linkage is developed when the product itself serves as an intermediate input downstream. An example of a forward linkage would be the business linkage between a grape-producing farmer or a cooperative and a winemaker who purchases these grapes and produces wine for the local or export markets. The graph below illustrates horizontal and vertical (backward and forward) linkages.

Graph: horizontal and vertical linkages in the value chain.

However, forming linkages is not an easy task.

Horizontal linkages (e.g. cooperatives) are faced with many challenges, including trust among farmers, the cost of cooperation (coordinating meetings, making decisions, etc.), and a free-riding problem, among others. As for challenges in developing vertical linkages, there are search costs of finding potential input suppliers or product buyers. In some cases, credit constraints may prevent the formation of a backward linkage, especially for start-up agricultural cooperatives as are common in Georgia (due to a lack of collateral, ill-prepared bookkeeping, etc.). There are also other transaction costs related to the formation of contracts as well as complying with some new regulatory environments. Examples of the latter are various food safety and traceability requirements found in modern agricultural supply chains around the world. In developing countries, such regulations are often too costly for value chain actors to comply with. On the other hand, such requirements are the main drivers of linkage developments, because they imply higher interdependence among value chain actors. Lastly, regardless of the regulatory regime, many customers require a certain quantity of products supplied on a regular basis for the products they purchase and sell to final consumers. In developing countries, most small-scale farmers are not up to these challenges. However, while one farmer in isolation can hardly develop business networks and meet the increasingly high quantity and quality standards for agricultural products, some of the challenges may be overcome through collective action such as forming agricultural cooperatives.

For more than three years, the government of Georgia and donors led by the European Union have been supporting the development of agricultural cooperatives across the country, an initiative we have previously discussed in detail in several blog articles. While many agricultural cooperatives were formed in the country and some of them already overcame the main challenges of forming good horizontal linkages, the main challenge of making these cooperatives sustainable still remains. One of the key success factors for this is having good vertical integration in the chain.

Several successful cooperatives in Georgia have already managed to form stable backward and forward linkages. In some cases, such vertical linkages are even formed inside of cooperatives when a cooperative is involved in several stages of a value chain. The formation of second-level cooperatives will further contribute to developing sustainable linkages in Georgian agricultural value chains.

The successful business model of the “Samegobro 2014” cooperative could be summarized as follows:

• The strong value chain linkages (both horizontal and vertical) that are based on win-win economic relationships. This is definitely the case for our trout cooperative, wherein each and every member is benefiting from being a member of the cooperative, be it in purchasing inputs or selling trout together.

• Seek to access higher-value markets and more profitable functions within the value chains. Although the trout sector has a short value chain in Georgia (and mostly ends at the “plate size” trout consumption, being either fried or boiled), besides the increased production volume, the cooperative also diversified its income source. Namely, they started making their own roe and fries and selling the fries to other farmers. In addition, the cooperative members are building cottages around the trout ponds and plan to offer visitors touristic services, including delicious trout dishes for lunch.

In conclusion, horizontal linkages such as farm cooperatives are a good start, but not enough. Having good vertical linkages and adding higher value in the chain is essential for the development of sustainable business models in Georgian agriculture. The modern value chains are not about competing on their own, but about being more integrated into the chain and working together for “a bigger pie”.

* * *

This article has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under the European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) and Austrian Development Cooperation, in partnership with CARE. Its content is the sole responsibility of ISET-PI and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, and CARE.