15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

03

July,

2017

Monday,

03

July,

2017

Monday,

03

July,

2017

Monday,

03

July,

2017

Back in 2014, Georgia and the European Union (EU) signed an Association Agreement, which included the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) between the EU and Georgia. While this agreement creates new opportunities for Georgia’s agricultural exports, high food safety standards in the EU market make it difficult to fully utilize these opportunities. This is particularly true for products of animal origin, which are subject to strict regulations. The necessary standards were successfully met last year for Georgian wool (fleece), and it became the first animal product to be exported from Georgia to the United Kingdom market (which is still a member of EU – for now). This is success, indeed!

Wool production was an important source of income for Georgian sheep farmers in the past. During the Soviet era, Georgia had more than 2 million sheep (around twice today’s sheep population), which used the winter pastures along the Caspian Sea. Wool processing and the textile industry were well-developed, and the price of greasy wool was 12-15 Manet per kg. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Georgia experienced a shortage of winter pastures, because it lost access to pastures along the Caspian Sea; moreover, the country also lost the traditional Soviet market for sheep products. Like many other industries, wool manufacturing collapsed.

Today, the main source of income for sheep farms is the sale of lambs and sheep cheese (specifically for Tushetian shepherds), while wool plays an insignificant role in income generation for farmers (Kochlamazashvili et al, 2014). There are only two operational processing factories in Georgia, with old, Soviet era machines…

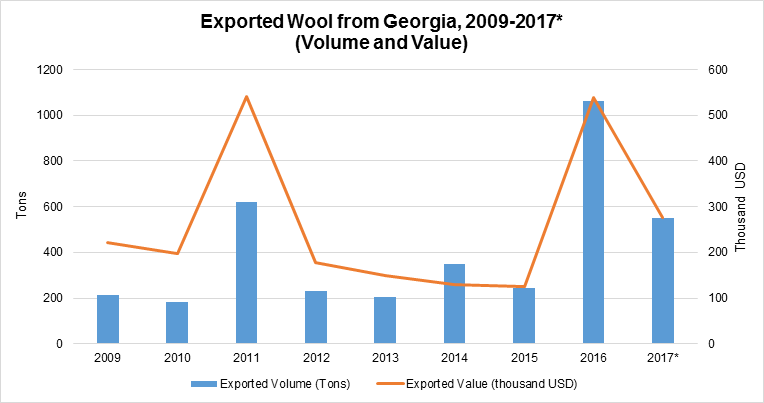

According to Geostat, Georgia produced 2,000 tons of wool in 2016 (on average, 2.4 kg wool per sheep). From the total amount of sheared wool in 2016, more than 50% (1,062 tons) was exported as a greasy wool to the following countries: Turkey (77%), Ukraine (10%), India (9%), the United Kingdom (2%), and Pakistan (2%).

Prices differed across export partners. The United Kingdom paid the highest price ($773/ton) in 2016, followed by Ukraine ($694/ton), India ($641/ton), Turkey ($463/ton) and Pakistan ($389/ton). On average, the exported wool price in 2016 was $507 per ton. Five wool exporter companies operated on the Georgian market in 2016, and two of them hold a market share of 78%.

The rest of Georgia’s wool was partly used domestically to make woolen garments, while big chunks of wool were wasted (either burnt or trashed). This waste of resources is not only an economic problem, but also harms the environment…

Even though there has been some success in increasing and diversifying Georgia’s greasy wool exports, including in the EU, the price of Georgian wool has been on a decreasing trend. According to the head of the Shepherds Association of Georgia, Beka Gonashvili, farmers are getting 30-40 tetri per kilogram of greasy wool, which does not cover even the cost of shearing and transportation. This demotivates farmers to produce good quality wool, and even worse in some cases – farmers burn or throw away the wool. The situation can only be changed if price of wool becomes higher… How can this be done?!

One wool-processing factory, “Tusheti,” has partly managed to break this vicious circle. This company pays one lari per kilogram of good quality wool, and farmers are motivated to deliver a high-quality product. However, currently this factory can purchase only 25-30 tons a year, which is a drop in the ocean, considering total wool production in Georgia. “There is more demand for processed wool (washed, dyed, yarn, felt, etc.), however, we cannot meet the demand due to our limited capacity for wool washing and our drying facility (as well as the old machinery used for spinning and yarn making),” says the director of Ltd Tusheti, Dito Arindauli.

According to Kochlamazashvili et al (2014), wool industry development can bring jobs and income for rural people and less environmental damage to Georgia’s nature. Tushuri sheep breed has coarse wool, which provides good material for carpet and felt-making (however, price of coarse wool is low on the international market). Wool processing techniques are very old, and still a widespread tradition among rural women in Georgia. In addition, colleges and schools make wool products for sale – woolen socks, hats, souvenirs, traditional thick felt, etc. The demand for semi-processed wool is on an upward trend, because woolen clothes and accessories are becoming popular among Georgians, as well as tourists. Georgian wool products are also getting international attention. For instance, two Georgian sisters from Tusheti, opened a woolen garment making school named “Shepherd’s House” in Rome, Italy. Their felt cloaks with icons on it are used by the Patriarch of Georgia, Ilia II, and Pope Francis, the Bishop of Rome. Moreover, the Kotilaidze sisters recently worked with a bag brand TL-180 (a French-Italian designers’ brand based in Paris) for the Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Tbilisi.

In addition, new technologies suggest that coarse wool is a good material for the construction industry. Not only is it a natural fiber, it has good thermal insulation qualities, which makes it energy efficient. The Heidelberg Cement Georgia has already been cooperating with the wool processing company Tusheti for several years.

The government and donors should help this sector in developing new products and new markets that would add value to Georgian wool. After creating value-added products, equally important is that this value is fairly distributed across the value chain actors. As with all agricultural value chains, the key is better coordination and cooperation between actors. For example, both adding value and fair distribution of margins could be addressed by forming wool cooperatives. Farmers in such cooperatives might be able to shear, collect, classify, process and market the wool together, which would potentially lower their costs and/or create higher value. Joint marketing will also create better bargaining power and prices for the farmers.

So far, there are not many wool cooperatives in Georgia. One example is the wool shearing cooperative that was established in the Tushetian community with the support of Caritas Czech Republic a couple of years ago. In order to address the coordination failure along the wool value chain actors, this donor recently decided to facilitate the entire value chain development – to support the wool processing company Tusheti, as well as connect it with wool shearing cooperatives and later to woolen garment making enterprises, in order to produce added value products locally, according to the project manager at Caritas, Anzor Gogotidze.

Those initiatives should be accelerated to avoid wasting wool. Increased wool export (including export to the EU market, which was highly facilitated by another donor, the Swiss Agency for the Development and Cooperation (SDC) and implemented by Mercy Corps) and the development of the wool processing and textile industry could bring this wasted resource back into the economy, creating more jobs and income for the country. Let’s hope that Georgian wool will become the “Golden Fleece” again, as it was in the famous myth on Jason and Argonauts, told of the gold-haired winged ram held in Colchis (one of the earliest Georgian formation).

* * *

*Kochlamazashvili, I., Sorg, L., Gonashvili, B., Chanturia, N. and Mamardashvili, Ph. (2014): Value Chain Analysis of the Georgian Sheep Sector. Study elaborated for Heifer International.

* * *

This article has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) and Austrian Development Cooperation, in partnership with CARE. Its content is the sole responsibility of ISET-PI and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, and CARE.