31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

19

March,

2018

Monday,

19

March,

2018

Monday,

19

March,

2018

Monday,

19

March,

2018

This year Georgia’s electricity market will have to go through some crucial reforms. The signing of the Association Agreement and Georgia’s accession to the energy community in October 2016 imposed some important obligations on the country to reform its energy markets. For the electricity market, 2018 will be a turning point. Among the key obligations, the country committed to under the energy community accession protocol were the adoption of: (i) Directive 2009/72/EC, concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and (ii) Regulation (EC) No 714/2009, on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in electricity. Provisions from both of these documents have to be incorporated into Georgian legislation by the end of the year. This entails some crucial steps to ensure non-discriminatory access by any third party to the electricity market. To meet this obligation, Georgia will have to:

1. Unbundle vertically integrated companies in distribution and generation according to provisions of EU directive 2009/72/EC

2. Create a functional trading mechanism to ensure access of third parties to the market. This will most probably entail the set-up of a day-ahead market.

At a first glance, Georgia's electricity market does not currently experience any major problems in operations. So, are we reforming the market just because of these obligations, or are there any additional reasons?

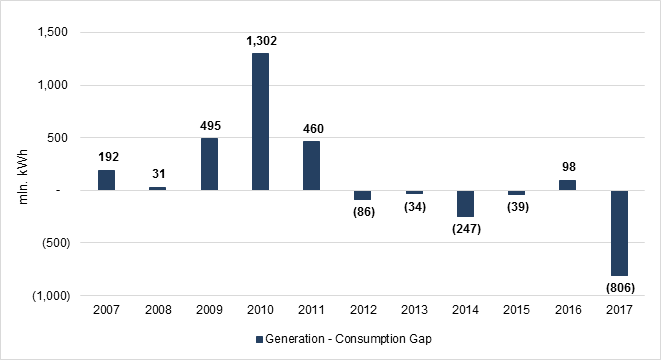

Georgia’s current market structure can be described as reliable, as it provides relative stability in pricing for all market participants, from generators to customers. However, such a highly regulated market structure does not provide efficient pricing, as it is very unresponsive to changing circumstances (Newbery 2018). In the end, this can lead to underinvestment in electricity generation – something we may be already experiencing in Georgia’s electricity market. A possible indication of this phenomenon is an increase in the consumption-generation gap over the past five years, peaking in 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Consumption-Generation Gap in Georgia

So far, the Georgian government, in order to attract more investments in generation, has been offering potential investors the opportunity to sign power purchase agreements (PPAs). These are government guarantees to investors that the electricity system commercial operator (ESCO) will purchase electricity from newly built power plants for a fixed price during certain months and over a certain number of years. This practice, however, was stopped earlier this year (upon the recommendation of the IMF). This is not necessarily bad news. Government guarantees such as PPAs can create a bias towards investing in certain generation technologies, rather than others (depending on the preferences of the government). As the government is not always able to ensure the most efficient allocation of resources and may respond with a lag to market developments, this might lead to overinvestment in more mature technologies and underinvestment in more modern (and potentially more promising) ones. However, eliminating government guarantees for long-term investments such as electricity generation, while keeping the current market structure, could result in a reduction in the flow of new investments in this sector. In turn, limited investments, coupled with growing demand, could be expected to lead to an increase in imports and a reduction in energy security, with an expected acceleration in customer electricity prices. May the ongoing reform process improve this picture?

The issue of electricity reforms related to vertical unbundling and the creation of trading mechanisms on the market has been widely studied in the economic literature. However, the results are not unanimous. Erdogdu (2011) analyzed data from 63 developed and developing countries and found that in developing countries, unbundling was likely to lead to price increases, while in developed countries a combination of unbundling and privatization of state-owned enterprises had a decreasing effect. ESMAP (2011), using data for 10 countries, suggested that full vertical unbundling would reduce electricity tariffs, while partial unbundling (not separating generation from distribution) had no significant impact on tariffs. Nagayama (2007), using data from 83 countries, suggested instead that taking on their own, unbundling, and/or the creation of trading mechanisms on the market would not have any impact on prices. However, in combination with the establishment of an independent market regulator, unbundling could contribute to price reductions.

Several studies also show that electricity market reforms that open the market and unbundle larger private ownerships can have a positive impact on GDP growth (Carvalho 2016). Some of the reasons for this can be increased access to the electricity market, leading to larger investments and corresponding spillover effects on other sectors of the economy. The positive impact of market reform on investments is confirmed by another recent study by Balza, Jimenez, and Mercado (2013), studying 18 Latin American countries.

In addition to encouraging new investments, a well-functioning electricity market can also play a major role in ensuring better investment decisions and facilitating investment flows towards the most efficient (and/or the most profitable) power generation technologies available (as opposed to the potentially distortive effect of government PPAs). In the case of Georgia, market liberalization could possibly also contribute to the creation of new opportunities to fill the seasonal consumption-generation gap of the country. Under a market framework that captures all types of the costs and benefits created during power generation, more investments may go to countercyclical renewable power generation technologies, such as wind power, which would increase the generation potential in periods when demand is higher than supply and prices are the highest.

Reforming the electricity market is fairly complicated, and despite much positive evidence from the economic literature, there are a large number of issues policymakers should take into account in the process. For example, taken separately, the individual components of the reform may not be able to lead to a positive impact on electricity market performance. Instead, careful planning of the reform steps would be more likely to yield good results. Among the main elements to take into account, a few deserve a particular mention.

Vertical unbundling in combination with a working electricity trading mechanism is key to the success of the reform. Without unbundling it is impossible to ensure unlimited third-party access to the market. Consequently, it will be less likely that new investments will take place in the electricity sector.

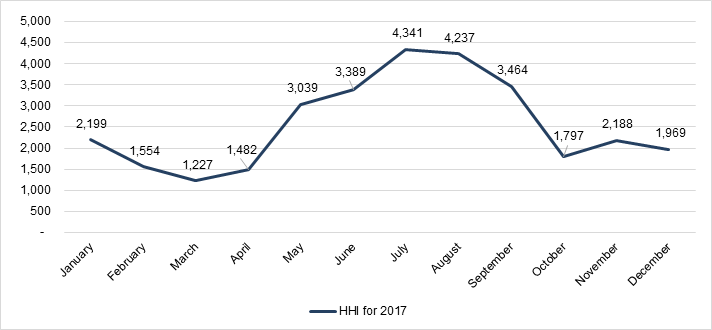

The trading mechanism on the electricity market can only function if there is no market power in the generation sector. At this stage, the picture is the opposite. As to the amount of installed capacity, the Georgian market is fairly concentrated between state-owned enterprises, distribution companies, and one large corporation – Georgian Industrial Group. One way to show how concentrated the Georgian electricity market is would be to calculate the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). This measure varies between 0 (very low concentration) and 10,000 (highly concentrated). Looking at the total installed capacity on the Georgian electricity market, the Index is 2,398, which indicates a moderately concentrated market. However, it is important to note that due to the seasonality of the Georgian electricity market, the HHI index can vary substantially during the year (Figure 2). This complicates market reform, underlining that over some months of the year (May-September), when the market is highly concentrated, the larger generators can be expected to have better access to the market and a greater opportunity to abuse their market power.

A potential solution to this issue could be the privatization of state-owned enterprises (except Enguri and Vardnili, privatization of which is complicated for political reasons) and possibly the provision of alternative (and less distortive) guarantees to investors (especially during the initial stage of market operations, which are characterized by greater uncertainty) to partially offset the elimination of PPAs.

Figure 2. HHI index by generation over the months of 2017

As we already mentioned, this year is going to be a turning point for the Georgian electricity market. Decisions made during the reform process will shape the sector for the coming decades. The potential for the reforms to produce positive developments is high. However, with opportunities also come potential risks. Therefore, implementation of the reforms needs a thorough analysis and corresponding fine-tuning along many dimensions.