02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Tuesday,

27

November,

2018

Tuesday,

27

November,

2018

Tuesday,

27

November,

2018

Tuesday,

27

November,

2018

On 28 November, the Georgian Central Election Commission (CEC) will hold the second round of the very last direct presidential election in Georgia before the constitutional pivot to indirect elections. This is the last stage of a political reform aiming at replacing the presidential political arrangement with the parliamentary system. The president’s powers in the new system will be extremely limited and largely symbolic.1 Nevertheless, political parties are considering the presidential elections of 2018 to be a rehearsal for the more influential parliamentary elections of 2020 and, therefore, the battle for the presidency appears far more intense than one could have imagined before the first round.

According to the CEC, slightly more than 1.6 million Georgians voted in the presidential elections, with one of the highest attendance rates in Georgia’s recent history - 46.74%.2 The main competition was between Salome Zurabishvili - an independent candidate supported by the incumbent political party Georgian Dream (GD) and Grigol Vashadze - the opposition’s candidate nominated by the United National Movement (UNM), and nine further oppositional parties. The battle was so tight that no candidates were able to cross the 50 percent threshold to win the first round, and the difference between the two leading candidates was less than a single percentage point – Salome Zurabishvili received 38.64% of the total votes, leaving Grigol Vashadze only slightly behind with 37.74%.

The results were completely unexpected for the leaders of the ruling political party. Beforehand, the Georgian people appeared quite loyal to the incumbent party, granting them a constitutional majority in the recent parliamentary elections (2016) and the rule of nearly all Georgian municipalities in the recent local self-government election (2017). Confidence in their victory was so apparent that the leaders of Georgian Dream were barely involved in the pre-election campaign, and rather than nominating their own candidate, they supported an independent – Salome Zurabishvili.

Politicians and analysts have identified three main reasons that might explain the failure of the ruling political party in the first round of the presidential election. Firstly, even the leaders of the incumbent party recognize that socio-economic problems (poverty, unemployment, inequality, depreciation of the national currency, over-indebtedness, inflation, etc.) have caused dissatisfaction with the government’s performance. Secondly, some of Zurabishvili’s statements regarding the Russo-Georgian war, 2008, were regarded as unacceptable to a large part of society. Thirdly, the opposition parties mounted an aggressive pre-election campaign to discredit the ruling party’s candidate. The following section will consider in-depth statistical information from the results of the first round of the presidential election and the distribution of votes relating to various characteristics.

It is widely recognized that incumbents have structural advantages over challengers during elections. This phenomenon is known as an incumbency advantage. The incumbency advantage might emerge as name recognition, ease of access to campaign finances, access to government resources that can indirectly boost a campaign, and sometimes even the possibility of determining the timing of elections. Certain aspects of the incumbency advantage are common, not only for developing countries but also for western democracies.3

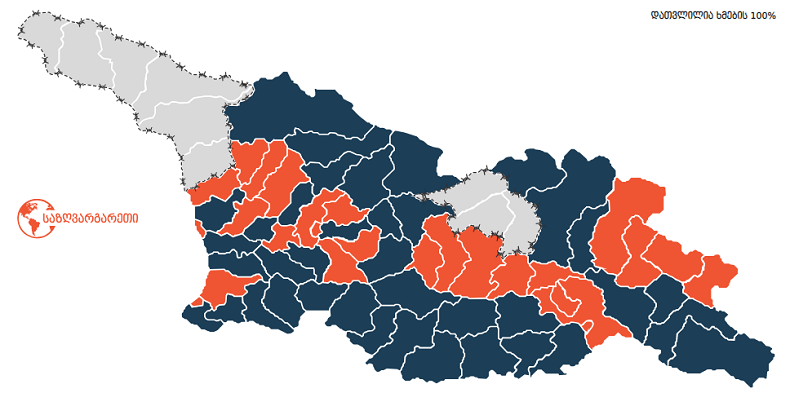

Despite the incumbency advantage, votes in the first round of the presidential election were quite evenly distributed between the two leading candidates. The only region where the candidate endorsed by the ruling political party received more than 50% of the votes was Samtskhe-Javakheti, while the leading opposition candidate received slightly more than half of the votes from Georgian polling stations abroad.

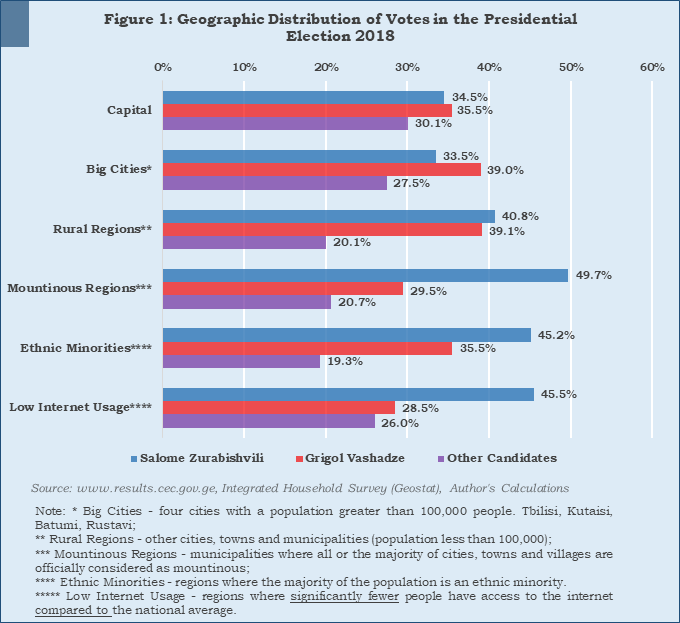

Moreover, the capital, as well as the four largest cities in the country,4 voted for the opposition’s leading contender, while the rural population, and people living in small towns, voted for the incumbent party’s supported candidate. Ethnic minorities and those living in mountainous regions were also solidly behind the pro-Georgian Dream presidential candidate (these regions typically vote for whoever is currently in power). Moreover, Salome Zurabishvili managed to collect a notably higher number of votes than her main opponent in regions where the population generally has low internet usage.

It is interesting to observe the distribution of votes based on their economic sentiments and expectations. According to the Integrated Household Survey (IHS), 41.7% of the sample claimed their family’s financial state worsened in 2017, while 52.4% of people suggested their financial situation had not changed, and 5.9% of the people surveyed experienced some financial improvement. Certain pessimistic sentiments of the Georgian population could potentially have had a negative impact on the number of votes gained by the candidate supported by the incumbent party. As expected, the leading opposition candidate still slightly outperformed the Georgian Dream-backed independent candidate in regions where significantly more people held negative sentiments compared to the national average. In addition, Vashadze managed to collect more votes than Zurabishvili in regions where the majority of people cannot fulfill their basic needs and have limited access to the water and gas supply infrastructure.

Grigol Vashadze also somewhat outperformed Salome Zurabishvili in regions where significantly more people either anticipated no change or had negative expectations about the financial state of the future. However, the candidate supported by the ruling political party managed to dominate in regions where significantly more people were optimistic about the country’s future financial state.

The reader may be left to interpret the extent of this statistical information. Though, with only a few days left before the second round of the presidential election, it is still quite hard to predict who will be the fifth president of Georgia. The only thing that can be boldly stated is that voters have a very difficult decision to make. Regardless of the results of the election, the ruling party needs to learn a valuable lesson from the election process to better prepare for the decisive upcoming parliamentary elections.

1 The president’s powers are particularly restricted if an incumbent political party has a constitutional majority in parliament, as is the case in Georgia.

2 It is notable that this is the highest participation rate since the crucial 2012 parliamentary elections. For instance, the parliamentary elections of 2012 drew 44.99% of eligible voters, the presidential election of 2013 – 32.1%, the local self-government election of 2014 – 28.94%, the parliamentary election of 2016 – 34.79%, and the local self-government election of 2017 – 29.84.

3 Peskowitz, Z. (2017). Ideological Signaling and Incumbency Advantage. British Journal of Political Science: 1–24. De Benedictis-Kessner, J. (2017). Off-Cycle and Out of Office: Election Timing and the Incumbency Advantage. The Journal of Politics. 80: 119–132

4 Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Batumi, and Rustavi, the cities with a population greater than 100,000 people.