10

July

2023

10

July

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

14

June,

2019

Friday,

14

June,

2019

Friday,

14

June,

2019

Friday,

14

June,

2019

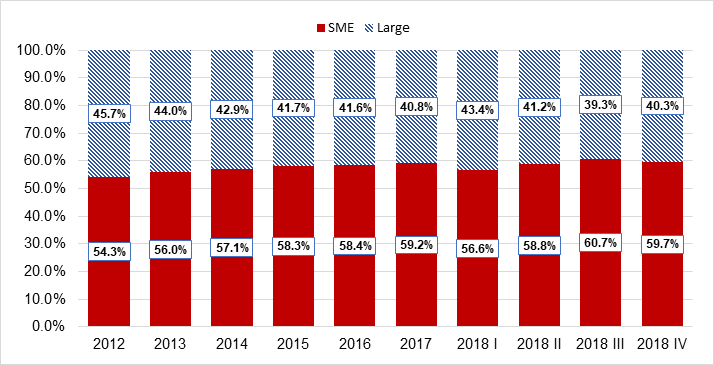

In technological terms, there has never been a better time to be a small or medium size business owner: people can always get ahold of you and you can work wherever you need to. Creating an additional source of income catches people’s interests all over the world; as additional motivation, we often hear about the launch of yet another program directly helping these businesses, thus making it easier to become a start-upper. And here, the rhetorical question: “why not?!” pops into some people’s minds. Starting a small or medium size enterprise (SME) serves as an accessible route to joining the business sector because of low management costs, working with less capital and more intense labor with inexpensive products, and having the capacity to adapt rapidly. Global trends come as evidence of this — according to the World Bank Group, the majority of the business population is in the form of SMEs, “formal SMEs contribute up to 60% of total employment and up to 40% of national income (GDP) in emerging economies. These numbers are significantly higher when informal SMEs are included.” The Georgian business environment replicates global trends (Figure 1), as the difference between the share of SMEs and large companies in total production is easily noticeable.

Figure 1: Share of SMEs in Total Production

Even though starting a small business sounds attractive, nothing comes without a price: an unfavorable macroeconomic environment, low economies of scale, poor institutional and regulatory framework conditions, market size, and lack of technology add a huge component of uncertainty to the “bright business future” of SMEs and makes companies fight against them. Still, SMEs are vital actors and key contributors to value-added globally, so it is not surprising that they have gained importance in the economic development of emerging economies. In many cases, implementation of institutional and regulatory frameworks is not enough to “bleach” the various obstacles to the formation of SMEs, but there is one additional remedy in the form of Business Support Organizations (BSOs), more commonly known as business associations. Up to this point, you might have thought that this blog was about SMEs, but now, it’s obvious that the main “character” has just appeared on the scene.

According to the World Bank, BSOs support and strengthen the development of the private sector and they “represent an increasingly important form of participatory development in developing countries”. BSOs are intermediary bodies linking two major sectors: the public and the private, they also serve as a bridge to connect SMEs and the government to form more cooperative relationships. In general, these organizations help business representatives make their organizations more independent and self-sustaining.

A unique combination of strengths, linking the government and the private sector, offering firms a collective voice and taking collective actions, a vehicle for providing principal services—these are just a few of the things you can read about BSOs in the economic literature and reports. BSOs’ role is internationally recognized, and their positive impact is economically measured. One of the major contributions of BSOs to the economy is that they make businesses more independent from the government.

BSOs can come in many shapes and sizes. BSOs operate in different sectors: agriculture, manufacturing, industry, etc. Although the industries may differ, the core roles and missions of BSOs remain extremely similar, thus they can be characterized by similar management structures, memberships, and financial policies. Doner and Schneider (2000) discuss the market-supporting and market-complementing activities of BSOs, which lead to economic growth (Table 1). When BSOs support the market, they put indirect pressure on policymakers, contributing to the provision of property rights and effective public management. When they complement the market, these organizations coordinate directly with member firms, lower costs of information, upgrade the quality of production, and set standards or inform members of new ones. Training, general business counseling, and loan packaging can also be included in their activities. Yet, the domestic market is not the only playing field for BSOs. Hutchinson, Fleck, and Lloyd-Reason (2009) prove their necessity in assisting retailers in the process of international expansion. BSOs give retailers the chance to successfully “establish a presence in overseas markets” (Hutchinson et al., 2009).

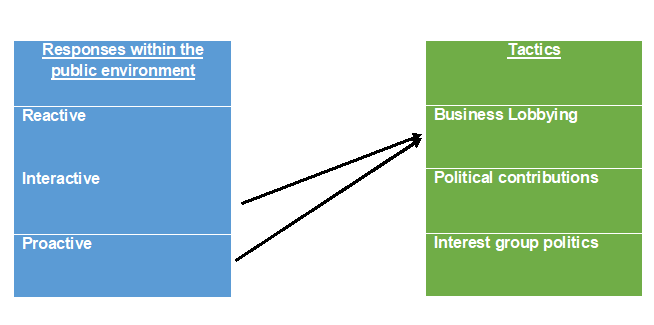

The relationship between BSOs and the government may take various forms of interaction (Table 1). Mainly, this connection is aimed at helping the private sector stay informed about public policies and adapt to them quickly. The reactive type of response to public policies is the most aggressive approach; it is perceived as the least productive of the relationships. This cannot be said about the dialogue and interactive response modes; they serve as fundaments for the development of “partnerships or coalitions to advance new policies and programs. Proactive behavior is intended to help future pressures and adjustments to such changes. As for the tactics — business lobbying, political contributions, and interest group politics — businesses use to impact policymakers (either through individual efforts or BSO platforms), they may differ according to their specific level of influence on the government. Tactics and responses might be used in combination to affect the decision-makers. Proactive and interactive lobbying is regarded as the most productive approach.

Table 1: Forms of interaction between the government and BSOs by Gittell, Magnusson, and Merenda (2013)

ISET Policy Institute and the Georgian Farmers’ Association conducted the “Business Support Organizations Needs Assessment” in 2017-2018, which draws a picture of the challenges these organizations face in Georgia and the gaps that they fail to fill. This research looks at the issue not only from the business association side but also from the points of view of member and non-member SMEs: while enterprises (SMEs) are aware of the importance of BSOs in their development, in most cases the BSO services offered to them are not alluring. Also, many of the companies (49.1%) are not ready to pay high membership fees; a maximum of 10-50 GEL monthly is acceptable. Another problem is the lack of communication — 68% of the enterprises interviewed have never received a membership offer from any organization. It is evident that the membership-based approach is not financially stable for BSOs in Georgia. The main sources of income for the majority of BSOs are donor-financed projects and delivery of consultations and other diverse services, which remain unstable as a means of financing.

As for the communication between the state and Georgian BSOs, the survey indicates that the government is, for the most part, ready to listen and understand the needs of BSOs and their members; policymakers are open and ready for dialogue. However, actual steps are not being taken to solve the issues, and public officials’ engagement in BSOs’ activities is minor and mostly expressed through participation in exhibitions organized by BSOs.

One more challenge is the organizations’ structures, which remain at a rudimentary level; BSOs do not have the proper tools or substantial economic resources to share their expertise with their members effectively. Based on the understanding of the environment for BSOs in Georgia, the business association community is still at the initial, survival stage and has great opportunities for progress and success — still, this will not be possible without proper engagement from the government and all stakeholders.

Considering this situation, the lessons learned and tendencies that have to be changed regarding Georgian BSOs, their state can be summarized thusly:

• For the financial sustainability of BSOs, the tendency of donor-dependency should be changed and replaced by membership fees;

• BSOs are characterized by irregular communication with member companies and potential members;

• The majority of BSOs do not have a formalized management structure;

• Relationship and feedback mechanisms between BSOs and the government are not developed in a formalized way; BSOs should be actively engaged in establishing new regulations. They should be an instrument for the government to provide SMEs the opportunity to adjust smoothly and without interruption to new regulations before they are enacted.