30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Sunday,

22

April,

2012

Sunday,

22

April,

2012

Sunday,

22

April,

2012

Sunday,

22

April,

2012

This year, approximately 113 baby boys are born in China for every 100 baby girls; 112 boys per 100 girls in India, 111 in Vietnam. The looming social crisis stemming from the significant gender imbalance in the countries of East and Southeast Asia has been in the media spotlight for a long time. Unfortunately, the problem of gender imbalance is not confined to Asia.

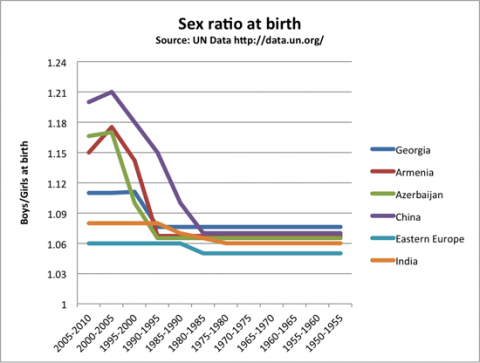

According to the UN database, between 2005 and 2010, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia held second, third and fourth place in the world after China in gender imbalance statistics. The ratio of boys to girls at birth in these countries was 1.16, 1.15, and 1.11 respectively. With the natural ratio being somewhere in the range of 1.05-1.08, such high numbers of newborn boys are impossible to achieve without artificial intervention.

Even more alarmingly, the male to female ratio increases rather than declines for the cohort of children under 15 years of age. For example, according to 2011 estimates, in Georgia, the boys/girls ratio at birth is 1.11 versus 1.15 for those under fifteen years old. In Armenia for the same year, the ratio increases from 1.12 to 1.15, and in Azerbaijan the increase is from 1.11 to 1.13. While far from being conclusive evidence, this increase may nevertheless be indicative of a further problem – the situation where scarce family resources – such as food, access to medical care – are allocated towards sons at the expense of daughters.

In general, the preference towards male offspring has both cultural and economic roots. For example, according to Christophe Guilmoto, a senior fellow in demography at the IRD, France, the skewed sex ratio can be observed in patriarchal societies where following marriage, the female traditionally becomes a part of her husband’s family structure and no longer contributes economically to the family of her birth. China, Korea, and India are examples of such societies.

Thus the problem of preference for males can be cast as a classic case of externality. In societies where children are a form of investment and where the return on bringing up a girl cannot be completely appropriated by her family, there will be “underinvestment” in females. This leads to the phenomenon known as the “tragedy of the commons”. The balanced sex ratio is a common good, but precisely because its benefits accrue to the entire society and not to the family who brings up a girl, the balance is disturbed in favor of boys.

One interesting piece of evidence in support of the “tragedy of commons” explanation can be found in the evolution of the boys/girls ratio over time. As can be seen on the graph above, the balance began to deteriorate in the countries of the South Caucasus after the 1990s. In China - after the economic liberalization reforms of 1985. Could it be that the preference for boys became more pronounced exactly at the time when economic uncertainty became stronger, and when the old forms of social security started to fail, creating the need for extra “insurance”?

Of course, the gender imbalance is not a sustainable social equilibrium. One way or another, the self-correcting mechanism will set in. These changes, however, are likely to be slow and confounded by high social costs - such as major disruptions in the traditional family structure, the possibility of increased violence against women, and more aggressive and risky behavior on the part of men.

To overcome the tragedy of the commons, the government does not necessarily need to rely on subsidies. Improving social security schemes, or even more importantly, making a woman more economically empowered and independent in society could go a long way towards breaking the trend and preventing the social crisis scenario.