30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

28

March,

2016

Monday,

28

March,

2016

Monday,

28

March,

2016

Monday,

28

March,

2016

Back in October 2014, soon after the introduction of new visa regulations by the Georgian government, I visited Seoul, the capital of South Korea. An unpleasant surprise awaited me on the way back home at the Seoul airport. The young stewardess checked my (Israeli) passport and informed me that, according to the system, I will not be allowed to board the flight (to Istanbul) unless I show a Georgian residence card or buy a return ticket.

“But I live in Georgia, and it has never been a problem to come back, nobody ever checked my ticket”, I argued.

The stewardess apologized for the inconvenience but insisted – in a very pleasant Siri-ish voice: “According to the system, one has to have a return ticket or a Georgian residence card.”

Desperate to go back to my Tbilisi home, I initiated another round of negotiations.

“Look”, I said, “couldn’t there be a mistake in your system?”

“WE ALWAYS FOLLOW THE SYSTEM”, said Siri, demonstrating the futility of any further attempts to negotiate.

Ultimately, I managed to get on the flight because I found my (brand new) residence card among many other cards in my wallet, but this phrase – WE ALWAYS FOLLOW THE SYSTEM - stuck with me. It stuck because it seemed to encapsulate a quintessential truth about Korea (both South and North) – a deeply rooted tradition that “celebrates conformity and order”, as one observer put it. By the same token, “we always follow the system” is a great shorthand for everything that Georgia is not.

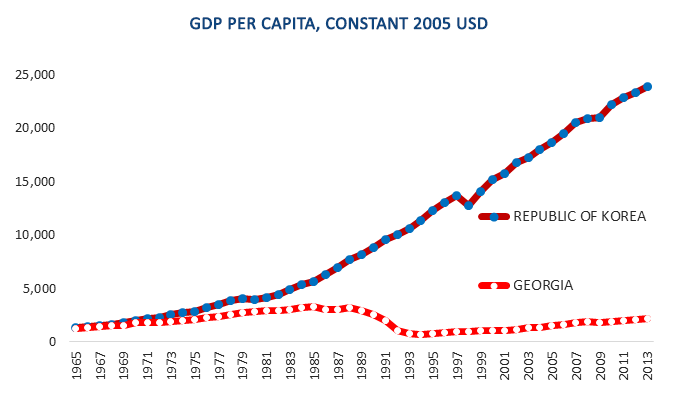

Conformity and order clearly have their advantages. One way to establish this is to plot South Korea’s GDP per capita growth over time alongside with that of Georgia.

While South Korea’s “miraculous” modernization, industrialization, and export-led growth are often compared to West Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder, President Park Chung Hee’s (1961-1979) authoritarian rule and industrial policies carry a much closer resemblance to those implemented by fascist Germany before and during the Second World War. In both cases, the state engaged in ambitious economic planning while co-opting powerful economic elites (family-controlled industrial conglomerates known as “chaebols” in Korea’s case), suppressing and destroying trade unions [1], engaging in nation-wide education and infrastructure projects, providing credit guarantees, but demanding, in return, that all economic activity should serve the national interest, however, defined.

As described on Wikipedia:

“Government-chaebol cooperation was essential to the subsequent economic growth and astounding successes that began in the early 1960s. Driven by the urgent need to turn the economy away from consumer goods and light industries toward heavy, chemical, and import-substitution industries, political leaders and government planners relied on the ideas and cooperation of the chaebol leaders. The government provided the blueprints for industrial expansion; the chaebol realized the plans. … the chaebol-led industrialization accelerated the monopolistic and oligopolistic concentration of capital and economically profitable activities in the hands of a limited number of conglomerates.”

When seen through this prism, South Korea’s miracle appears to be all about “FOLLOWING THE SYSTEM”: toeing the party line on industrialization priorities; relentlessly adapting foreign technology; willing to function under enormous pressure to perform in one’s studies and work; and, last but not least, sacrificing consumption and a “good life” today for the promise of a better future.

In a series of papers spanning several years, Daron Acemoglu, Philippe Aghion, and Fabrizio Zilibotti dwell on the changes firms (and, by implication, countries) must undergo as they get closer to the global technology frontier. A core feature of their models is the need for firms to eventually switch from imitation (investment and adaption of existing technologies) to innovation.

Whereas imitation is most effective in (South Korea-style) large, vertically integrated firms with a rigid hierarchical structure and disciplined workforce, innovation requires a smaller size of firms, a flatter hierarchy, and greater reliance on outsourcing. Innovation is also preconditioned on a system of incentives that encourages experimentation and forgives mistakes. If “need” is viewed as the mother of invention, a lack of “discipline” and the freedom to generate new ideas and try new practices may be portrayed as its “father”.

The Start-Up Nation, a bestselling book by Dan Senor and Saul Singer, describes the chutzpa of Israeli’s entrepreneurs and engineers as one of the key factors behind Israel’s astounding success as a hub of technological innovation since the 1990s. An eye-opening example in the book is that of Intel’s Israeli development unit having sufficient autonomy with Intel’s global hierarchy and the guts to engage the company’s headquarters in a fight over abandoning the dominant “clock speed doctrine” in favor of a new chip architecture emphasizing portability and energy efficiency.

“To cultivate a culture of disagreement and debate” was considered critically important for Dov Frohman, the founder of Intel Israel:

“The goal of a leader”, Frohman is quoted by Senor and Singer, “should be to maximize resistance – in the sense of encouraging disagreement and dissent. When an organization is in crisis, lack of resistance can itself be a big problem. It can mean that the change you are trying to create isn’t radical enough… or that the opposition has gone underground…”

It is important to realize that a lack of “discipline” is a double-edged sword. Indeed, Israel’s rebellious ethos, disrespect of authority, and the tendency to trick “the system” set it oceans apart from Korea’s Confucian spirit. It is at once a key factor behind Israel’s rise to prominence as a “start-up nation” and its failure to transform a larger number of its startups into global tech giants such as Korea’s Samsung, LG, or Hyundai.

A beautiful social TV ad, which I chanced to see several years ago, contrasted the incredible harmony of Georgia’s folk dance (shown in slow motion) with the chaos on Tbilisi’s streets (played on fast-forward, view from above).

Georgians consider themselves much more traditional and religious (92% and 95%, respectively) than South Koreans (22% and 30%), according to World Value Survey. Yet, while Georgians value time-honored traditions and religious commandments, “following the system” is not in the Georgian book.

As a rule, Georgians hate rigid rules (such as coming to work on time) and do not trust any “system”. This may explain why the architects of the “system” - Georgian lawmakers – seem to pay so little attention to fine-tuning new laws and regulations. Indeed, why bother if these laws and regulations (such as those designed to please EU bureaucrats) are likely to stay on paper.

The Georgians’ love of freedom does translate, as may be expected, into incredible creativity. Georgian painting and sculpture, performing arts, film-making, and writing are truly world-class. Yet, not properly managed, they fail to translate into commercial success, comparable to Italy’s.

Finally, Georgians are a very talented people as witnessed by their outstanding scholarly achievements in Soviet times. Georgian physicists, mathematicians, microbiologists, and medical surgeons were recognized leaders of the Soviet elite. Today, however, Georgia’s scholarly achievements are extremely modest and demonstrate no signs of improvement. Moreover, combined with unrealistic expectations about own abilities and “presidential” aspirations on the part of many Georgian males, poor education translates into very high unemployment and poor work ethic.

While the potential is certainly there, these contradictions do not bode well for fast catch-up growth through imitation (South Korean-style), or Israel-inspired innovation boom.

* * *