02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

02

May,

2016

Monday,

02

May,

2016

Monday,

02

May,

2016

Monday,

02

May,

2016

The Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement between Georgia and the EU, brought into effect in 2014, was hailed at the time by many as being of great importance to Georgian manufacturers and food/beverage producers. Yet, skeptics commented that 1) Georgia had already had more than 7000 articles duty-free and quota-free under the pre-existing GSP+ trade terms granted by the EU for many years, and 2) very few exporters had been able to take advantage of these concessions.

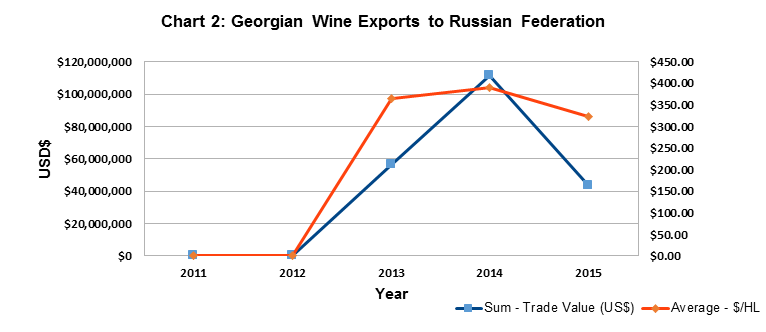

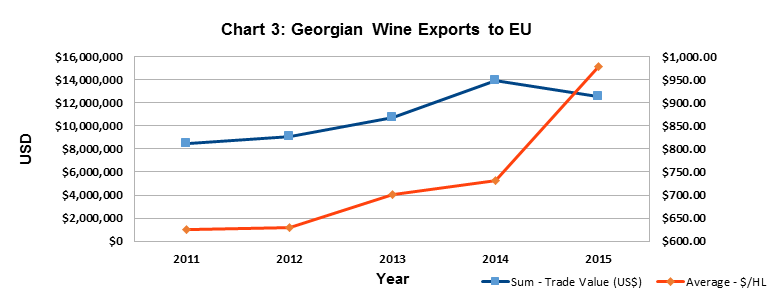

Georgia’s wine and spirits exports are an excellent case in point. While constituting the largest consumer market in the world, the EU makes up a small proportion of Georgia’s exports of wine (including not only bottled wines but also cask wines and bulk wine in flexitanks). Traditionally, Georgia has been a very Russia-focussed wine production country, as the following charts indicate.

Incidentally, 2013 and 2014 were boom years for Georgian alcohol producers: the Russian market reopened in 2013 and pent-up demand for Georgian wine meant that both sales volumes and prices increased.

As can be seen from visual comparison charts 2 and 3, Russia is a lower price market for Georgian wine than the EU. Characteristically, the mix of Georgian wines reaching the EU market includes a larger proportion of premium and super-premium wines as indicated by the much higher average price per hectolitre Georgian wine exports fetch in the EU. Despite that, in 2013-14, the urgency for diversifying into higher quality products and challenging new EU markets was dulled by the lure of familiar markets in Russia. Only a few shrewd operators maintained a counter-cyclical approach, leveraging their Russian sales revenues into aggressive European and Asian marketing campaigns.

Indeed, entering the European market is a great challenge for Georgian producers. European consumers, especially in the West and South of the continent, have quite well-defined preferences and in many cases have been drinking the same wines from the same appellations for hundreds of years. Changing those preferences will not be easy. The proverbial “wine lake” of Europe means that table wine in Europe is cheaper than mineral water in many cases. Georgia does not effectively compete in this market segment, lacking the subsidies or economies of scale to do so.

Yet, crucially important for the future of Georgia’s future economic development, the DCFTA with the EU must be seen as only the first - not last -- step in restructuring Georgia’s international trade!

Having gone through the process of DCFTA negotiations, increasing safety standards, and dealing with non-compliance to satisfy the EU, Georgia is now institutionally equipped to push through deals not only with the EU but with China, ASEAN, South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, India, and NAFTA.

One of the fastest-growing centers of wine consumption in the world, China is poised to exceed Russia as a wine-consuming country before the end of this decade. Until early this century, what little wine that was consumed in China was mostly domestic and of very poor quality. One author of this article can vividly remember buying a bottle of “Great Wall” Cabernet in 2000 in Shanghai, which had a can of Coca-Cola taped to the neck of the bottle as a free gift. The serving suggestion was to blend the two, which would make the wine almost drinkable; otherwise, it tasted like furniture polish.

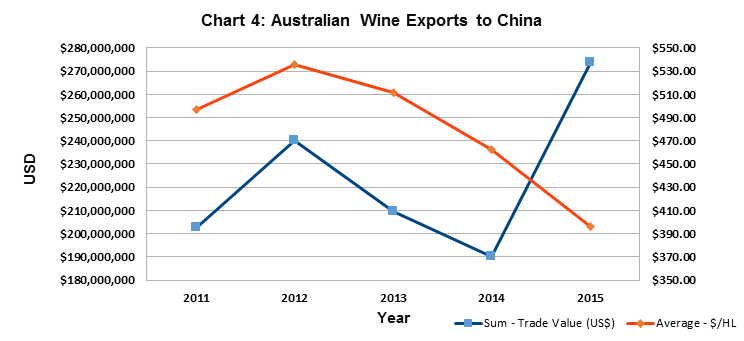

In only 15 years, wine drinking has become a prestigious activity in China, indicating sophistication. China will soon have one of the largest areas under vine in the world. Vineyard management and winemaking quality are dramatically improved. Wine imports have also boomed, with over a third accounted for by French wine. Yet, we should pay special attention to the success of New World exporters, such as Australia, taking advantage of the fact that many Chinese consumers have yet to establish fixed habits regarding the country of origin of their wines.

Georgian wine exporters have been capturing market share in China, from a very low base. Import tariffs on wine imports into China are 14%. Negotiating an FTA with China will eliminate this tariff, boosting Georgian wine exports into this lucrative market. It is interesting to observe that France commands the highest premium in the East Asian markets, judging by the average price per hectolitre commanded by exporters, yet and Georgian and Australian wines fit a respectable niche in the next tier, commanding significantly higher prices than Chilean or South African wines.

Raising the efficiency of rail transport from Georgia across the Caspian to China is another important way to promote Georgia exports to East Asia. Faster and cheaper rail transport could put Georgian wine exports at a competitive advantage over those from South America, Africa, Australasia, and Western Europe, which have to rely on sea freight.

Australian exporters have been able to capture significantly better prices on average than most of their competitors, through rigorous quality management, national and regional branding, and aggressive export marketing. Importantly for our comparison, both Georgia and Australia are (almost) zero-subsidy jurisdictions. Georgia maintains floor prices for grapes produced by smallholders, but there is no substantial subsidy for commercial-scale vignerons.

It is still too early to see the effect on Australia’s Free Trade Agreement with China, effective December 2015, yet this FTA has significantly reduced the cost of Australian wine to Chinese distributors (the tariff of 14% of the Cost-Insurance-Freight value is now abolished for Australian wine) which allows flexibility for discounting to capture market share, improving margins, or a mix of these strategies.

$6 billion a year wine import trade in the Asia Pacific region still has plenty of growth potential. Moreover, for wine producers in countries other than France, Georgia included, the opportunity exists to capture market share amongst first-time wine drinkers who are not yet firmly wedded to European wines.

Only 20 years ago, Australian wine was unknown in Asia. Now it is ubiquitous. The export market promotion has evolved over time, with levies imposed upon wineries and grape growers to fund export market development, vineyard R&D, and biosecurity programmes with government co-operation.

Brand “Australia” is now well known, and consumers understand the diversity of products available under that umbrella, from the supermarket “critter wines” like Yellowtail at $5 to $3000/bottle Penfolds Grange. Regional/appellation identities like Barossa Valley, Margaret River, and Rutherglen are understood by consumers within the larger national wine identity.

The significance of Australia’s experience for Georgia goes well beyond wine or alcohol. Provided Georgia uses a smart export promotion strategy, one led by industry with government co-operation, we can capture market share in nuts and many niche products like Kiwifruit, blueberries, honeyberries, and blackberries. Essential components of a successful marketing strategy for Georgia would be national branding, effort invested in negotiating Free Trade Agreements (not subsidies!), and transport.

To sum up, the EU DCFTA is an excellent development that may yield incremental gains for Georgian exporters, from a low baseline, in very attractive consumer goods markets. However, it should not be seen as an end unto itself, but the first of many Free Trade Agreements negotiated with non-traditional markets.