10

July

2023

10

July

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

06

February,

2017

Monday,

06

February,

2017

Monday,

06

February,

2017

Monday,

06

February,

2017

“The type of failure we’re talking about is like how frogs lay 20,000 eggs so a few wind up as adults sitting on a lily pad sucking down mosquito dinners” is how the author of the recent Newsweek article describes the rate of failure it takes to breed a handful of unicorns-tech startups valued at more than $1 billion. Failure has increasingly become a chapter in success stories; stories that inspire a new generation of entrepreneurs to try, fail, try again, and succeed.

Economics, as we have come to know it, is about the efficient allocation of resources. Resources move in a Schumpeterian destructive fashion to create innovative products and services to keep up with the appetite and sentiments of the market. The regulatory environment has a mandate to smooth the process by ensuring fast entry and fast exit of resources, so when the legal system becomes a stumbling block in the process, there is no one to blame but the institutional architects.

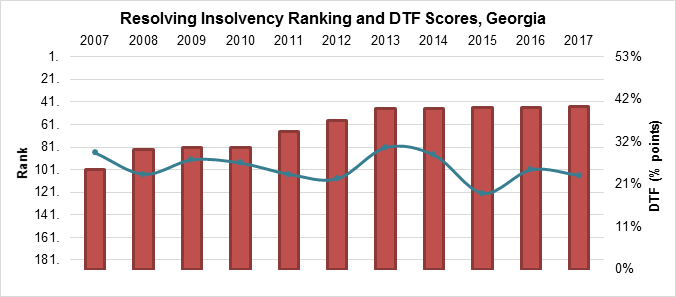

While it virtually takes less than a week to establish a business in Georgia, it might take several wasteful years to exit and free up the resources for a fresh start. Despite its reputation as a leading reformer in the region and beyond, Georgia steadily lags behind on international indicators assessing the insolvency framework in the country, e.g. Georgia is currently ranked 106th on the Doing Business Resolving Insolvency indicator, behind Niger, Mongolia, and Uzbekistan. Often-cited changes in methodology have nothing to do with the fact that the insolvency law in Georgia is manifestly bad, and despite continued promises from policy-makers, there are no signs of recovery.

Insolvency law guides the relationship between debtors such as entrepreneurs and shareholders, and creditors, such as banks and other institutions which lend in cash or in-kind, when debtors for whatever reason are unable to meet their obligations. Evidence illustrating a positive correlation between the strength of a country’s insolvency framework and economic outcomes is abundant, but an optimal insolvency framework depends on the legal background and other specificities of the country. 2016 Nobel prize laureate in Economics, Oliver Hart, recognized for his contribution to contract theory, argues that while there are no one-size-fits-all insolvency laws, there are general principles that every law should satisfy. He identifies three specific goals the law should try to accomplish.

Goal 1. Ceteris Paribus, a good insolvency procedure should deliver an ex-post efficient outcome.

In other words, the efficient outcome of an insolvency procedure is achieved when viable firms reorganize, while unviable firms exit the market. High recovery rates for creditors and low costs in terms of financial and time expenses of insolvency proceedings are also important. High insolvency costs discourage liquidation of inefficient firms and divert freed-up resources into productive use. Letting ailing firms exit increases the robustness of the economy, benefiting the whole society.

Goal 2. A good insolvency procedure should preserve the bonding role of debt by penalizing managers and shareholders adequately in insolvency states.

An insolvency regime is a tool to achieve financial discipline. Lenient insolvency procedures increase the risk of investors in case things go awry. Therefore, only high-risk investors will be willing to invest in countries with weak insolvency regimes. Lower downside risks would encourage a higher variety of investors to engage in entrepreneurial activities and therefore stimulate the economy.

According to the International Monetary Fund’s Orderly and Effective Insolvency Procedures Guidelines, the degree to which insolvency law is perceived as pro-creditor or pro-debtor is irrelevant. What matters is the extent to which these rules are effectively implemented by strong institutional infrastructure. A pro-debtor law that is applied effectively and consistently will generate greater confidence in financial markets than an unpredictable pro-creditor law.

Goal 3. A good insolvency procedure should preserve the absolute priority of claims, except that some portion of value should possibly be reserved for shareholders.

Reserving a portion of value for shareholders decreases the incentives for high risk-taking on behalf of shareholders in order to avoid insolvency or delay an insolvency filing.

Congruent with these general principles, the Doing Business Resolving Insolvency indicator evaluates insolvency regimes around the world in terms of their ability to secure the most efficient outcomes. Georgia’s performance is comparable to the Europe and Central Asia (ECA) region (excluding OECD high-income countries) on indicators such as: the recovery rate, which measures how many cents were collected out of the dollar by secured creditors from an insolvent firm at the end of the insolvency proceedings; the time needed for creditors to recover their credit, recorded in calendar years; and, the cost of the proceedings, recorded as a percentage of the value of the debtor’s estate. The outcome of an insolvency proceeding is most likely to be a piecemeal sale, rather than a sale as a going concern, which adversely affects the recovery rate.

The gap in performance is pronounced when it comes to the Strength of Insolvency Framework Index. In all sub-indices, Georgia’s insolvency regime scores remarkably low, particularly so for the Reorganization Proceeding Index, indicating its minimal compliance with internationally accepted practices for reorganization and restructuring, and for the Creditor Participation Index, indicating limited participation of creditors in insolvency proceedings.

| Resolving Insolvency Indicators | Georgia | ECA | OECD (high income) |

| Recovery Rate | 39.5 | 38.2 | 73 |

| Time (Years) | 2 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Cost (%of estate) | 10 | 13.1 | 9.1 |

| Outcome (0 as piecemeal sale and 1 as going concern) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Strength of insolvency framework index (0-16) | 6 | 9.9 | 12.1 |

| Component indices | |||

| Commencement of Proceedings Index (0-3) | 1.5 | - | - |

| Management of Debtor's Assets Index (0-6) | 3.5 | - | - |

| Reorganization Proceedings Index (0-3) | 0 | - | - |

| Creditor Participation Index (0-4) | 1 | - | - |

Source: World Bank Doing Business 2017

Assessments of other direct and indirect stakeholders are consistent with the Doing Business ratings. According to the assessment report produced by USAID project, “Governing for Growth (G4G) in Georgia,” the current “law adversely affects the rights of senior secured creditors, largely ignores the rights of unsecured creditors, and does not provide a flexible enough framework for “rehabilitation” to be a useful strategy for either debtors and creditors.” The German Economic Team assessment identifies two key aspects in which the Georgian framework fails to conform to international best practices. The first key aspect is that its main focus is on the liquidation of insolvent companies, rather than on rehabilitation. The second aspect concerns the limited institutional capacity to manage insolvency cases, such as an absence of an established profession of private insolvency officeholders (temporary management while the company is engaged in insolvency proceedings).

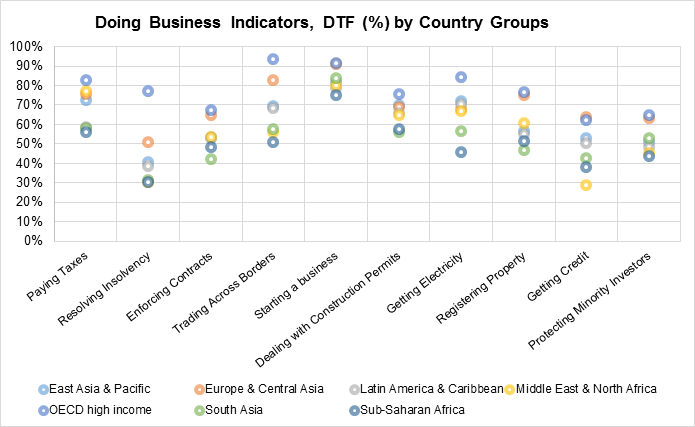

Observing the overall regulatory performance of Georgia in recent years, it is difficult to explain what has taken us so long to develop in this particular area and bring it up to international standards. The chart below could offer a hint to solving this puzzle. The dots of the chart illustrate the average distance to frontier (DTF) scores for each group of countries by each Doing Business indicator. The DTF score measures the distance of each economy to the “frontier,” which represents the best performance observed on each of the indicators across all economies in the Doing Business sample since 2005. Looking closely at the difference in DTW scores between OECD High-Income Countries and less affluent countries, one can observe that the gap between the scores is the largest for the Resolving Insolvency indicator. This is a clear illustration of the complexity in this regulatory area. Improving performance goes beyond redrafting simple laws and deregulating different sectors of the economy, and requires institutional development and capacity building on a larger scale. In particular, given the complex and pressing nature of insolvency proceedings, effective implementation calls for judges and case administrators who are efficient, and adequately trained in commercial and financial matters, and the specific legal issues raised by insolvency proceedings (IMF).

The complexity of implementation is exacerbated by political economy issues that arise in transition periods whenever a country considers reforming its insolvency framework. Even if debtors and creditors jointly favor more efficient procedures, this may not be the case in the short run in the existence of debts negotiated under previous terms (Hart, 2000). Pressure from conflicting interests can also delay policy design and implementation processes, and create regulatory frictions.

Many countries are embarking on this challenging route to upgrade their regulatory framework and institutional infrastructures. According to the Doing Business reports, the most popular trends among reformers in the past three years include:

- Introducing a new restructuring procedure

- Improving the likelihood of successful reorganization

- Strengthening creditors’ rights

To summarize, the economic costs of an ineffective insolvency framework are substantial and are realized through higher interest rates for borrowers, investor reluctance, and loss of economic activity by potential entrepreneurs or entrepreneurs that have to prematurely leave the market without a chance for a fresh start. To catch up with modern market dynamics, Georgia needs to create a regulatory framework where a failure is an affordable option, and do it fast.