02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

27

March,

2017

Monday,

27

March,

2017

Monday,

27

March,

2017

Monday,

27

March,

2017

“Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school” – Albert Einstein

It is widely recognized that education is the key to the future. In general, educated people have higher earnings and lower unemployment rates and highly-educated countries grow faster and innovate more than the other countries. Therefore, in the recent economic literature, education is considered as an investment good and look for the other investments, there are the costs and benefits of the investments in the education. The cost of education is the value of the time (opportunity cost) and money (tuition fee and other fees) people spend to acquire a secondary school certificate, professional education certificate, or university diploma. While the benefit of gaining an education is a premium in earnings for graduate people (there are other benefits as well like better working conditions, recognition, and achievements at work). Empirical Literature suggests that there are two channels from which education affects earnings. First, it improves workers’ skills that, in turn, raises the productivity of labor and leads to higher wages. Second, higher education provides the credentials that signal employers that the candidate has appropriate skills for a certain job.

The human capital approach is based on the idea that individuals have to compare these costs and benefits and decide to which degree to stop. If benefits are not large enough to compensate for costs, the individual might think that it is not worthwhile to gain an additional degree. Therefore, while we are considering the decision of the ordinary people on how much to invest in education, it is important to determine what is the earning premium of the additional degree. However, the world is not that simple and there are plenty of other socioeconomic factors that play an important role in the decision to continue studying or drop out (Lemieux, 2001). This blog article will try to measure the effect of education on earnings in Georgia by controlling main socioeconomic factors that might have a significant influence on wage distribution.

Georgia is a transition economy, with massive structural changes in the first decade of the transition process that significantly worsen the socio-economic situation of the country. After wars, unsuccessful institutional reforms, hyperinflation, inefficient taxation system, and permanent budget sequester, building a sound education system became a low priority for the Georgian governments. Therefore, before the Rose Revolution, there were three main problems in the education system: corruption, low access to education, and low quality of education. Despite such a poor condition in the education system, there was high demand for higher education. After Rose Revolution, the corruption and affordability problem was successfully solved, while the quality of education still remains one of the most challenging areas.

Much of the economic literature on the effect of education on earnings has been inspired by the seminal work of Mincer (1974) and Becker (1975) on human capital. Mincer (1975) captured the return to education by estimating simple OLS regression, where log earnings are considered as a dependent variable that is explained by the number of years of education, potential experience, and squired term of potential experience. This blog article considers the modification of the classic Mincer equation by controlling a large number of the socioeconomic factors that also contribute to people’s earnings. As a dependent variable, we used log of earnings, where earnings are defined as: wage of the hired worker based on the written or oral agreement, the income of the entrepreneurs working on their enterprises and farmers’ income, earnings of the people working without hiring in the non-agricultural sector (manufacturing, trade, transportation, construction, handcraft, repair or professional activity – a reporter, a medical diagnostics, treatment and consulting). Moreover, the main interests of this research are two dummy variables that represent professional education and higher education (other lower levels of education is considered as a base). We controlled the experience of people by age, gender of the individuals, ethicality, and rural-urban distribution of people, marital status, and sectors of employment. This simple OLS analysis is based on the yearly data of the Integrated Household Survey (HIS) from 2008 to 2014 provided by Geostat.

First of all, among all the people present in the sample 20% to 24% have any form of tertiary education, while the same number for the employed people who earn any income is much higher 42%. In addition, the proportion of people with any type of professional education is 20% to 22% in the whole sample and around 25% among employed people. Georgia is distinguished by low levels of illiteracy, as only 0.5% to 1.15% do not know how to read and write. Corresponding statistics again indicate that gaining higher education is very popular among Georgians. However, the main question is how professional and higher education helps people to earn more income. The main findings of the regression analysis are presented in table 1 (some variables that were controlled are not presented on the table to avoid overload of the table).

Table 1: Results of the modified Mincer equation

| Variables | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Professional Education | 6.2%*** | 3.7% | 3.7% | 4.3%* | 5.0%** |

| Higher Education | 46.7%*** | 43.2%*** | 47.0%*** | 46.9%*** | 44.9%*** |

| Age | 3.6%*** | 3.6%*** | 4.3%*** | 4.2%*** | 2.7%*** |

| Age squired | -0.04%*** | -0.04%*** | -0.06%*** | -0.05%*** | -0.03%*** |

| Male | 35.6%*** | 35.8%*** | 34.6%*** | 30.9%*** | 26.4%*** |

| Rural | -11.2%*** | -5.9%*** | -9.7%*** | -15%*** | -6.2%*** |

| Tbilisi | 34.9%*** | 34.2%*** | 31.1%*** | 32.6%*** | 32.1%*** |

| Non-reg. married | -8.9% | -11.6% | 3.7% | -15.8%** | -19.3%*** |

| Single | -8.7%*** | -3.0% | -7.1%** | -9.4%*** | -5.9%** |

| Divorced | -1.2% | -12.9%* | -8.2% | -5.3% | 1.6%*** |

| Mining and Quarrying | 86.4%*** | 213%*** | 213%*** | 91.1%*** | 91.0%*** |

| Manufacturing | 53.3%*** | 56.8%*** | 54.6%*** | 50.3%*** | 51.8%*** |

| Electricity | 81.3%*** | 83.1%*** | 57.0%*** | 73.4%*** | 280%*** |

| Trade | 49.5%*** | 53.4%*** | 49.4%*** | 49.3%*** | 46.9%*** |

| Financial | 91.8%*** | 88.8%*** | 91.3%*** | 80.9%*** | 84.5%*** |

| Education | 33.3%*** | 40.1%*** | 27.9%*** | 33.7%*** | 27.9%*** |

| Constant | 3.82*** | 3.84%*** | 3.92%*** | 4.06%*** | 4.46%*** |

| Observations | 14377 | 7377 | 7777 | 7960 | 8165 |

| Population size | 3,025,452 | 3,012,067 | 3,187,662 | 3,260,734 | 3,353,555 |

| Flipping Age | 41 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 39 |

| R2 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.29 |

Source: Authors' calculation using Integrated Household Survey (IHS)

People with higher education earn 40% to 51% more compared to those with general education. However, earning premiums is fluctuating over time and do not reveal a clear pattern of increase or decline. While higher education is a big driver of earnings, professional education is shown to contribute relatively little 4% to 6% and again reveals no clear trend with time.

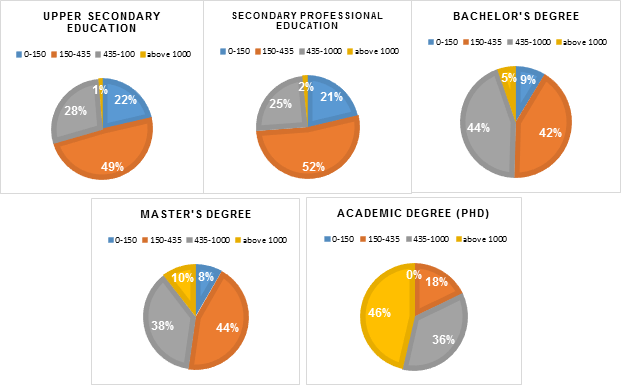

Despite the fact that tertiary education has a significant earnings premium, the rate of return on the additional year of schooling is still low compared to the other countries (Jugheli, 2012). If we decompose earnings into the four groups for different levels of education (0-150 lari low earnings, 150-435 lari lower than medium earnings, 435-1000 higher than medium earning, and 1000 and above high earnings), we will discover that as education level increases, the people concentrated in the low earning groups shrink significantly, while high earning groups increases. This finding again supports the idea that education has an earnings premium. However, the share of individuals with comparatively high earnings is higher in Bachelor’s or Master’s degree group, but the indicator itself is low even for these groups, showing that only 5% and 10% of individuals, who have Bachelor’s and Master’s degree respectively, earn income above 1000 lari. Despite the fact that IHS underestimates earnings, this distribution still gives us the information that the wage level in the country is low even for individuals, who have higher education. Therefore, we can conclude that people without a diploma of higher education have difficulties competing with the people with tertiary education for highly paid jobs, but the diploma itself does not guarantee high earnings.

Figure 1: Earnings distribution for different levels of education

Furthermore, it is important to estimate earning premiums for higher education in different cohorts. Therefore, we divided the total sample into three cohorts. The first cohort represents people with soviet education. The second cohort represents people who gained higher education after the collapse of the Soviet Union and before the Rose Revolution. The third cohort is the new generation that gained an education after Rose Revolution. As there is a huge amount of retired people among the first cohort, we decided to focus on the other two. People with higher education in the second cohort earn 40.6% more compared to those with general education in the same cohort. While the same measure is slightly higher 43.4% for the third cohort. Therefore, we again see that there is no significant difference between earning premiums among the generation. This finding again indicates that the third problem in the educational system – low quality of education is still relevant.

In addition, there is a significant gender gap in Georgia, as male earns 26% –45% more compared to a woman with more or less similar characteristics. Despite the large figures, the gender gap is closing over time. There are two main reasons for the high wage gap: low salaries in the sectors that are dominated by the women, such as education, health, and social security, and restaurants and hotel service (horizontal segregation) and lack of women in the leading positions (vertical segregation) (Sefashvili 2011). Furthermore, the wage premium from higher education differs with gender. A male with higher education earns 39% to 41% more compared to a man with general education. The same measure is higher 49% to 52% for female workers. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that men without higher education are highly concentrated in the sectors with higher earnings than women without higher education.

In addition, earnings in the rural areas are 2.5% – 18% lower than the earning in the urban areas rather than the capital of the country. The average earnings of the people living in Tbilisi are 25% - 34% higher than the other urban areas. However, it’s worth mentioning that the cost of living in Tbilisi is much higher than in other areas and much of the high productivity and highly paid sectors are situated in the capital. Furthermore, the earnings premium of higher education in Tbilisi, other cities, and rural areas are much closer, amounting to 46.3%, 42.8%, and 41.9% respectively.

Moreover, it is important to determine the effect of the sectoral distribution of workers on their earnings. In our model, the base sector is the agricultural sector and all the other sectors are compared to it (some sectors are not presented in the table not to overload it). It is clear that the agriculture and education sectors are characterized by the lowest wage premium. The agricultural sector has the highest concentration of people without high education (65% have maximum upper secondary education) that partially explains lower productivity and relatively lower wages in this sector. However, in the case of the education sector, more than 75% of people have higher education and 14.57% professional education, but the earnings premium is still extremely low. In addition, according to the recent statistics of Geostat, the education sector was the lowest-paid sector in the fourth quarter of 2016, where the average salary of the hired workers was only 589.2 lari that is 71 lari lower than the average salary of the second-lowest agricultural sector, 476.7 lari lower than the average salary of the country and 3.43 times lower than the average salary of the highest-paid financial sector. This statistic again gives us a reason to be concerned, as low-paid teachers and lecturers lose motivation to teach students better and young talented undergraduates have no incentives to become teachers or lecturers. Furthermore, lower motivation and lack of qualification lead to low quality of education. In addition, only a relatively less skilled part of undergraduate students (of course, with the exceptions of the talented enthusiasts) will choose this profession that further reducing the motivation and qualification of future teachers and lecturers. Therefore, we are in a vicious circle and should try our best to find a way out of it.

This blog is based on the research performed by the ISET-PI team for the Asian Development Bank “Good Jobs for Inclusive Growth” project.