15

November

2021

15

November

2021

ISET Economist Blog

Wednesday,

12

April,

2017

Wednesday,

12

April,

2017

Wednesday,

12

April,

2017

Wednesday,

12

April,

2017

Back in 2013, the Government of Georgia (GoG) approved a new law entitled “On Agricultural Cooperatives.” The primary goal of this legislation was to support agriculture and rural development in the country by strengthening agricultural cooperatives. Since then, agricultural cooperatives have been springing up like mushrooms; 13,000 farmers have already been registered in 1,500 cooperatives. In order to strengthen their capacity, donors led by the European Union have been providing financial assistance as well as trainings and advisory services to cooperatives and their members. According to ENPARD (European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development), 250,000 people have received advice on farming through 59 information and consultation centers, and more than 8,000 farmers have received EU-funded training in agriculture and business administration. Moreover, the ENPARD cooperative development component, implemented by five consortia led by CARE, Oxfam, Mercy Corps, PIN, and UNDP, has allowed 260 cooperatives to benefit from direct EU funding. To track the development of these 260 cooperatives, an Annual Cooperative Survey is conducted by the Monitoring and Evaluation working group led by ISET (a partner within CARE consortium). The most recent year’s development of these cooperatives has shown a positive trend in profit generation. In particular, compared to 2014 (the baseline year), the profit of cooperatives increased by 21% on average in 2015 (ENPARD annual cooperatives survey).

While these numbers are impressive and the primary goal – the quantity (big number of agricultural cooperatives have established) is achieved, agricultural cooperatives in Georgia still face a lot of challenges. This is the final year of ENPARD support for cooperatives (as we have already discussed in a previous blog), which gives rise to the question: who will survive in the long run?

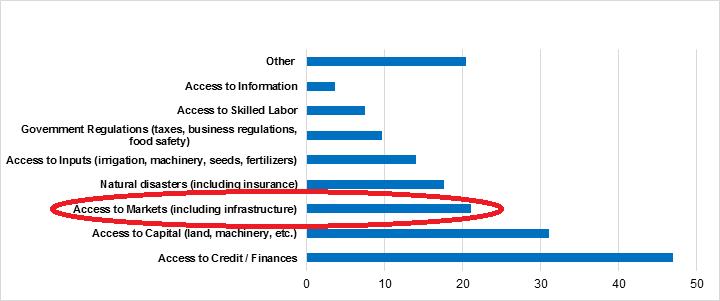

According to the survey, the progress of Georgian agricultural cooperatives is mainly constrained by a lack of access to credit, capital, and markets. While access to finance and capital is the most discussed problem related to farmers’ cooperatives, little attention has been paid to the issue of access to markets and the constraints that farmers face with product branding, selling, and realization.

Figure 1. Constraints on the Success of Cooperatives (Scaled score by the number of responses and priorities)

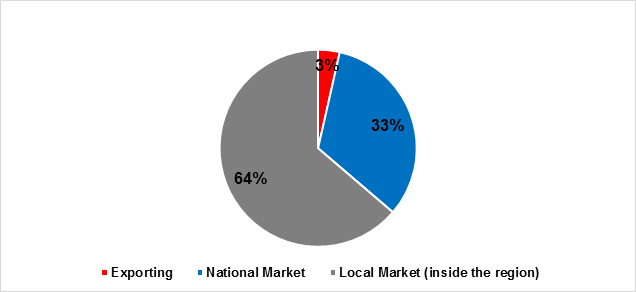

Returning to our question, a cooperative, like any other business, first of all, will survive if it is profitable. In order to survive as a business, one of the important components is to have access to markets and sell products. According to the ENPARD annual cooperatives survey, 64% of surveyed cooperatives sell their products inside their region at local markets, 32.5% sell outside of their regions, and only 3.5% export (directly or via exporter). In addition, there are two main channels of marketing: cooperatives sell their products to wholesalers or/and to local consumers (directly).

Figure 2. Geographical Area Where the Cooperatives Sell Their Products / Services

Buyers often face problems interfacing with small farmers because of their small sizes, the heterogeneous quality of supplied products, and poor organization and communication, leading to high transaction costs. The absence of institutions (like groups) and services deter farmers from overcoming these challenges and creating a win-win situation. From a business standpoint, weak vertical coordination can be a pre-determinant for a cooperative’s market failure that will probably be transmitted through the value chain and adversely affect farmers.

Nowadays, the most common types of agricultural cooperatives in Georgia are production cooperatives. This is not very surprising, as, at the very beginning of the cooperative movement, the main emphasis was on production; farmers were given mini-tractors and inputs such as bee-hives. In contrast, most of the western-style cooperatives that are successful examples operate in the service sector (agricultural service cooperatives), not in the production sector. In a service cooperative, members carry out their production activities independently, and the cooperative provides them with a range of services – machinery, input purchasing, packaging, distribution, marketing, etc. (Lerman, 2013). Through economies of size, service cooperatives manage to achieve lower costs in input purchasing (they make bulk purchases of inputs) and members benefit from the service cooperative, as they have a price advantage for the integrated sale of members’ products.

The difference between those two types of cooperatives was not well-understood at the beginning of this movement, starting with policy-makers (neither the law about agricultural cooperatives reflects it) and moving down the line to farmers. In the meantime, the first steps towards forming service cooperatives have already been made: ACDA has started to support the sector’s specific and targeted initiatives (though the implementation of such programs is still questionable); furthermore, the main emphasis is moving from production cooperatives to service cooperatives.

How can Georgian cooperatives overcome the constraints they face with selling their products and have better access to markets? One solution could be to establish marketing cooperatives (these are subcategories of service cooperatives): “Cooperatives that collect and prepare members’ produce for sale, truck it to the market, and arrange for actual sale at prices that are higher than what would be normally attained by the farmers themselves.” (Lerman, 2013) Cooperation in marketing allows farmers, who produce the same or similar products, to cooperatively market and sell their products.

In Georgia, the marketing system has a largely informal character; most cooperatives cannot reach the markets, as they do not have sales channels for market products (some cooperatives also lack transportation equipment). In order to sell the produced products, informal markets are established after the harvest. The creation of well-functioned marketing cooperatives will present agricultural producers with the opportunity to create more possibilities on the market, and they will be better integrated into the value chain. As a result, the farmers will improve their bargaining power against processors, traders, and other actors in the chain; they will have greater control over their own products, and their gain will also be greater. Furthermore, through marketing cooperatives, farmers could get contracts with large supermarket chains, hotels, and restaurants to supply a substantial quantity of their produce on a regular basis. Marketing cooperatives give producers the opportunity to obtain market authority and aid them in the equal distribution of risks and expenses. Such cooperation effectively utilizes available resources for satisfying consumer requirements, and therefore, cooperative members will have stronger incentives to collaborate.

Thus, providing incentives for farmers and cooperatives to create marketing cooperatives (either first or second level of cooperation) would be a good strategy to be considered for further development of cooperatives in Georgia. Perhaps farmers will perceive marketing cooperatives as a business opportunity (not as a legal entity that can bring to them grants and subsidies) and see the benefits from cooperation. And, again, who will survive in the long run? Apparently, only cooperatives with a strong business spirit will manage to pass through the fire.

* * *

This article has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under the European Neighbourhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) and Austrian Development Cooperation, in partnership with CARE. Its content is the sole responsibility of ISET-PI and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, Austrian Development Cooperation, and CARE.