Last week, The Economist published a comparison of the costs of pancake ingredients across many countries of the world. The pancake recipe used for the calculations included flour, eggs, milk, and butter – all of which are also part of the Khachapuri Index regularly compiled by the ISET Policy Institute. Thus, incorporating Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia was a piece of (pan)cake!

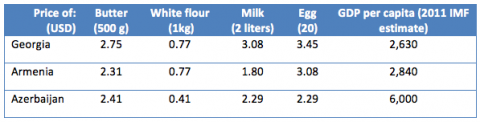

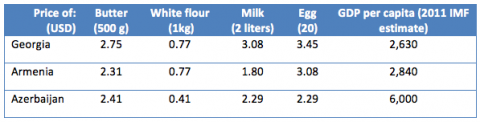

Table 1: Cost of pancake ingredients (12-15 portions) in the South Caucasus, USD

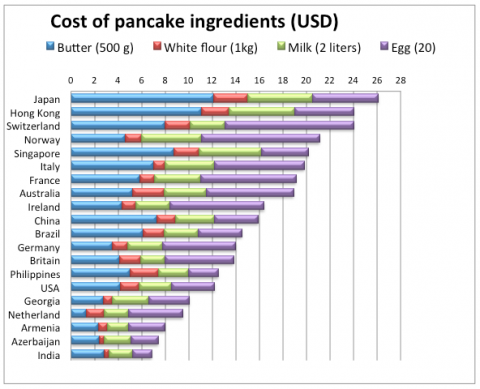

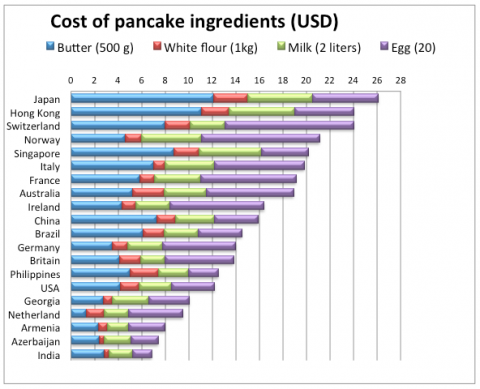

The good news is that pancakes (and khachapuri) are still a lot cheaper to cook in the South Caucasus than in the much richer Japan or Switzerland. No surprises there.

Table 2: International comparison of pancake prices

But how come pancake ingredients, and, in particular, flour and eggs, are so much cheaper in oil-rich Azerbaijan? With oil and gas export volumes at their peak, one might expect Azerbaijan to experience price inflation and a real appreciation of the national currency relative to its neighbors and the rest of the world.

Likewise, how come the most liberal economy in the region, Georgia, is more expensive than both of its neighbors? In recent years, Georgia has completely liberalized its trade, abolishing or dramatically reducing import tariffs, introducing modern customs terminals, simplifying import procedures, and eliminating corruption. And yet, despite all these trade liberalization measures, the price of flour – the bulk of which is imported to both Armenia and Georgia – is not lower in Georgia than in the much less liberal and land-locked Armenia.

We will leave the question of Georgia open for discussion by the blog readers. As for Azerbaijan, the answer may be relatively straightforward. First, Azerbaijan is a producer of grain. Second, Azerbaijan is a producer of oil and gas. Thus, Azerbaijan may be able to use a part of its oil windfall to directly subsidize domestic grain production (and consumption). Such a policy would disproportionately help the poor for whom food expenditures constitute a very large part of the family budget. For this policy to be effective, however, Azerbaijan would also have prevented the cheap grain and flour from leaving the country (for instance, Georgia). This could be achieved by means of establishing a state (or quasi-state) grain monopoly. I don’t know for a fact that such an institutional arrangement exists, but this would be my (easily testable) hypothesis.

Incidentally, the policy of providing cheap bread (and pancakes, and Khachapuri) for the “populace” is probably as old as the world. For example, in Ancient Rome:

Maintenance of [grain] supply was critical to survival, especially due to the policy of distributing free grain (later bread) to all Rome's citizens which began in 58 B.C. By the time of Augustus, this dole was providing free food for some 200,000 Romans. The emperor paid the cost of this dole out of his own pocket, as well as the cost of games for entertainment … The preservation of uninterrupted grain flows was, therefore, a major task for all Roman emperors and an important base of their power.

Source: Rostovtzeff, M., The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, 2nd ed., 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press.1957: 145.

The bread and circus tradition is still very much alive in today’s world: Egypt and other Arab dictatorships have for decades relied on food subsidies to ensure stability – a social contract so pervasive that the Tunisian scholar Larbi Sadiki described them as "democracies of bread." Israel – purportedly the only democracy in the Middle East – used strict price controls and subsidies for basic bread until as late as 2007, when these measures were replaced by another form of “targeted” government assistance for the poor.

Interestingly enough, the cheap bread policy of the Azerbaijani government is complemented by a large investment in popular entertainment and breathtaking architectural designs (see a previous blog post by Michael Fuenfzig). In just a couple of months, this policy will bear its first significant fruit as Azerbaijan will be hosting the 2012 Eurovision contest – the ultimate modern version of the Roman circus.

The views and analysis in this article belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views

of the international School of Economics at TSU (ISET) or ISET Policty Institute.

Wednesday,

29

February,

2012

Wednesday,

29

February,

2012