30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

15

October,

2012

Monday,

15

October,

2012

Monday,

15

October,

2012

Monday,

15

October,

2012

The private provision of childcare in Georgia’s cities has been on the rise during the last few years as is especially evident in the capital. Many of the new private kindergartens (KG) are said to provide very good quality services, helping enrich the set of preschool educational choices available to parents (or, rather, their children). Private KGs may be quite a bit more expensive relative to the public alternative, yet their share of the market is increasing over time, suggesting that more and more Georgian families are willing to pay a premium for better quality education.

Unfortunately, my attempts to get any precise (“official”) figures about the private part of the Georgian preschool sector were not successful. The fact that such data – whether current or historical – are not readily available to researchers like me creates the impression that nobody has ever tried to figure out what is going on in this very important sector, what problems (“challenges”) and opportunities are associated with its fast development thus far.

Knowing the share of the private sector in preschool education (and its dynamics over time and space) is very important when planning a reform of the national early learning system. We have some idea about the national average of overall preschool enrolment from GeoStat’s Integrated Household Survey. For instance, according to this survey, in 2011 the overall enrolment in the 3-5 age group was around 46%, of which about 9% attended private KGs. However, this estimate is based on a nationally representative survey that is not necessarily accurate when it comes to estimating enrolment rates at the sub-national level. In fact, it may be very imprecise given the large variation in the development of private KG provision across municipalities. We may suspect that private provision is very high in Tbilisi and low in, say, Oni.

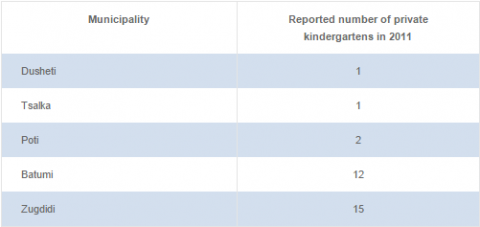

Yet, a special survey of all Georgian municipalities that has been conducted most recently by GeoStat revealed that 41 out of 65 local municipalities simply have no clue as to the true extent of private provision and the overall coverage of preschool children in their region. Of the remaining 24 localities that answered the question on private provision, 19 claims not having even a single private institution. As for those 5 municipalities that are aware of private KG provision in their locality, the situation is as follows:

Our attempt to deduce the approximate number of children enrolled in private preschools from the number of such institutions was also unsuccessful. Note that even those municipalities that appear to be aware of the number of private KGs do not know the number of children covered by these institutions. Batumi is the only Georgian municipality that is fully informed of the extent of private coverage.

No government agency, not even the Ministry of Finance was able to supply us with the number of private KGs operating in Georgia. No confidentiality is involved, they just do not know(!). One potential reason for this might be the loose legal framework for establishing a business in Georgia. It seems to be the case that when establishing a business, Georgian entrepreneurs are not required to disclose the precise nature of their business activity unless they operate in the food industry.

Given that the Georgian legislation does not distinguish between ordinary LLCs and childcare institutions, the latter are not subject to official sanitary, academic, or any other inspection. According to the representative of a private KG, we interviewed in Tbilisi, the quality of services provided by her institution has never been inspected by government agencies. And not because she was running a clandestine operation (the KG in question even has a website!). The implicit assumption behind such a lack of government oversight is this: parents are the best control mechanism.

For most private KGs this is really true. In one instance, a private Tbilisi-based KG installed online cameras that allow parents to watch their children play during the day. Of course, parents have no time for any Big Brother games. Rather, they rely on other parents’ recommendations and price as a signal of quality. A private KG would not be able to operate profitably in the long-term by signaling high quality (setting a high price) and under-delivering: even one unhappy parent can destroy their reputation. Consequently, parental control does help establish proper incentives for private KGs: incentives not only to implement a state-recommended standard (even if not enforced) but also to innovate and improve their services. This is so because, in a competitive environment, a KG’s stream of profits directly depends on customers’ satisfaction. Thus, when asked about the nature of the academic program offered by her KG, our interviewee reported implementing the Step-by-Step program, endorsed by UNICEF. This means that at least some private KGs really do try to keep up-to-date and deliver a service that corresponds to the price-based expectations of the parents.

The fact that parents pay on average 5 times higher fees at private compared to public KGs may suggest that there is a large quality gap between the private and public options. What is so special about private KGs? First of all, private KGs are smaller establishments, with a small number of groups and consequently, a small number of students. The teacher-to-child ratio, as well as the caregiver-to-teacher ratio, is higher in private KGs. As a result, more attention and care can be given to each child in comparison to a public KG. Second, private KGs offer greater flexibility and are less bureaucratic. Parents can drop off and pick up their children at their convenience. There is less paperwork involved as well. Finally, private KGs are directly accountable to the parents (“the clients”), allowing for closer coordination and continuous feedback.

According to the management of the private KG we interviewed, her institution is charging a fee of 300 GEL per month per child, however, they are able to offer discounts for children from relatively poor families. Of course, as a for-profit organization, a private KG cannot accommodate many such children, but if there is spare capacity (and, often, there is) such “humane” treatment could be offered. On the one hand, this can be seen as a simple price-discrimination tactic. On the other, however, it can help improve the image and advertise the KG in question. To sum up, even though private KGs are not subject to state inspections of their sanitary, hygienic, and academic standards, they do try to offer a good quality service in order to stay in business.

If private KGs are able to provide better educational services for those who can afford them, a country may be concerned with the social consequences of providing unequal access to education for children from poorer families.

While perhaps true in the abstract, such a concern is totally misplaced in Georgia, given that more than 50% of 3-5 y.o. children are excluded from the early learning system. This is potentially a real-time bomb if one considers the impact of preschool education on learning outcomes, labor productivity, and wages (see our previous blog post for an explanation).

Thus, the problem for Georgia is to expand the overall coverage of preschool children, not to obstruct the development of the excellent private alternative. While the private provision does primarily cater to the needs of the emerging middle class, a true barrier for greater social mobility in Georgia is the outright exclusion of the rural, poor, and socially disadvantaged strata of the population.

In fact, as long as the public education system is unable to provide universal coverage, the government of Georgia and/or individual municipalities may consider supporting the development of the private KG sector. For one thing, this could be done in a budget-neutral way by saving on the cost of building a new public KG. The private KG might have spare capacity to absorb a part of preschool-age children that are not currently covered. Instead of building new public KGs, the state could train teachers of private preschools and even subsidize the cost of private provision. Both measures would decrease the cost for parents and provide more children with access to higher-quality preschool education, changing their lives for the better.

Yet another option to consider is to introduce means testing and differentiated fees for public education, as is already practiced in Tbilisi. This measure would push some of the higher-income parents from public to private KGs, freeing the capacity of public KGs to take care of children from low-income families.

Our conclusion is that private kindergartens are not a problem or threat. Rather they are a huge opportunity.