30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

22

November,

2013

Friday,

22

November,

2013

Many of us have been lucky to be taught by great teachers, teachers who did not just teach, but inspired and brought out the best in us. Indeed, it is hard to overestimate the impact (positive and negative) of teachers on the children’s minds, their career prospects, and aspirations. Understandably, such impact is strongest in weaker social environments where THE teacher is often a beacon of light (and enlightenment), a ‘wailing wall’ of sorts, a leading moral and intellectual authority.

Despite that being so, the second half of the 20th century has seen the teaching profession going into freefall as far as its social esteem (and pay) is concerned. This apparently global crisis in public schooling has mainly affected the poor: the rich and the educated were able to adjust by opting for the far more expensive private options or re-discovering the “homeschooling” and “un-schooling” alternatives. Thus, the policy debate surrounding the teaching profession and the quality of public schooling is very much about a country’s commitment to social mobility as embodied in the ‘equal opportunity’ slogan.

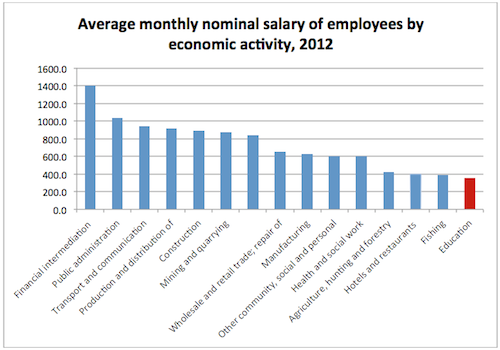

The collapse of Georgia’s state in the early 1990s has left the country’s education system in ruins. What should worry us today, however, is that judging by the 2012 level of salaries in the education sector (see chart), it hasn’t even started to recover, despite a succession of reform efforts and many millions spent on teacher training and retraining, school boards and guards, improvement of curricula and textbooks, investment in computerization and infrastructure.

While falling short of a comprehensive assessment, the Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M), which was carried out by National Assessment and Examination Center in 2008, speaks volumes about the low quality of Georgia’s future elementary math teachers: Georgia ranked last )!) among 17 participating countries both in teaching methods and subject comprehension (mathematics).

The relative social status of Georgia’s educators is surely a key factor in the country’s sorrow performance in international tests that measure students’ achievements in reading, math, and sciences. For example, in 2006 and 2011 Georgia was ranked 37/45 and 34/45, respectively, in the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), which examined the reading comprehension skills of children aged 9-10. While only aggregate results from these and similar tests are available to us at this time, it is clear that Georgia’s performance in these tests is a function of the country’s demographics and economic geography. Far more than half of Georgia’s population – the urban poor and subsistence farmers – have their children trapped in extremely low-quality public schools that fail to present them with an ‘equal opportunity, let alone prepare them for the 21st-century‘ knowledge economy’.

Georgia's current education system may have reached a point of no return, requiring new out-of-the-box solutions rather than more of the same teacher-training-curricula-reform type medicine. First and foremost, the system urgently needs new blood. And this is mainly about two things: prestige and compensation.

A few decades ago, teachers were a symbol of dignity in the Georgian literature. For example, a famous poem by Joseb Noneshvili (“Teacher”) idealizes teachers as societal role models and endows them with extraordinary spiritual characteristics: honest, loving, always happy, educated, patriotic and motherly. While going all the way back to this ideal may not be possible, it is also not necessary.

The main policy question is what can bring the best and the brightest among Georgian university graduates to the country’s smaller towns and villages in order to teach and contribute to a process of change. A simple but unaffordable option would be to dramatically raise teachers’ salaries. A more complicated but relatively inexpensive solution would be to launch a national program requiring (and enabling) the best university graduates – recipients of government scholarships – to give back in the form of a one or two year service as a teacher and/or community organizer in Georgia’s social and economic periphery.

For such a program to be effective, the young and inexperienced teachers will have to be trained and supported. Naturally, not all of them will develop a passion for teaching and staying. But many will, particularly if the government, the schools, and local communities in question will provide adequate incentives and resources.

* * *

As John Deprey has apparently said, “The apple doesn't fall far from the tree......unless that tree's growing on top of a hill”. The teacher quality debate in Georgia is about more than half of Georgia’s apple trees growing in a hole, with little light and no way to escape.