02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

07

September,

2015

Monday,

07

September,

2015

Monday,

07

September,

2015

Monday,

07

September,

2015

There is a distant rumble in the regional economy – one with a particularly Persian flair. Iranian commerce and exports are about to enter an unrestricted world market as part of the deal negotiated between Western partners and Iranian leadership over its nuclear enrichment program. If Iran can meet the terms of the agreement, sanctions on its exports and imports will be lifted within the next year. When such a large energy-producing economy goes from near autarky to free trade, this is bound to send ripples through the world economy. Georgia and the South Caucasus are in a prime position to benefit from increased Iranian trade, investment, and tourism.

Iran is a panther of an economy, but one with a muzzle over its jaws. According to the Wall Street Journal, the sanctions imposed on Iran by the UN Security Council, the US, and the EU are “the toughest the world community has imposed on any country to date”. Triggered by the International Atomic Energy Agency’s report regarding Iran's non-compliance with the Agency’s safeguards agreement, the UN sanctions included targeted measures ranging from the freezing of assets to an arms embargo, to selective travel bans, to restrictions on Iran’s access to banking and financial services.

The US went further by imposing an almost total economic embargo on Iran, including sanctions on companies doing business with Iran, a ban on all Iranian-origin imports, Iranian banks, and financial institutions. The US view, according to the US Congressional Research Service, is that “sanctions should target Iran’s energy sector that provides about 80% of government revenues, and try to isolate Iran from the international financial system.” In early 2012, the US froze all property of the Central Bank of Iran and other Iranian financial institutions, as well as that of the Iranian government, within the United States. At about the same time, the EU imposed an oil embargo on Iran, effective from July, and froze the assets of Iran's central bank.

Ironically, Georgia was able to benefit from the tightening of international sanctions on Teheran. In 2010, at the same time as US and EU toughened their stance on Iran, Tbilisi and Tehran agreed to a visa-free regime to facilitate bilateral tourism and business. Followed by the establishment of direct flights, the move allowed thousands of Iranians to flock to Tbilisi for either business or pleasure. It also created an opportunity for middlemen to find new ways to skirt sanctions.

“As Sanctions Bite, Iranians Invest Big in Georgia” was the headline of an influential Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article, published in June 2013. WSJ reported official data, according to which, the number of companies, registered by Iranians in Georgia shot up to 1,489 in 2012 from just 84 in 2010. Some of these, according to WSJ’s sources, may have acted as front companies for Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Georgia “for the purpose of evading sanctions and importing dual-use technology”. Many others, however, represented genuine investment, e.g. in agriculture, where Iranian entrepreneurs were able to take advantage of Georgia’s liberal legislation to acquire thousands of hectares of arable land.

The windfall of Iranian investment came to a sudden halt in summer 2013 when, pressured by the US government, the Georgian authorities decided to crack down on Iranian business activities. On July 2, 2013, the Georgian government unilaterally revoked the visa-free regime, froze 150 bank accounts held by Iranian companies and individuals, and put Iranian-owned Investbank under supervised management by the National Bank of Georgia. Just a few days earlier, on June 28, the Georgian parliament passed a bill imposing a moratorium on agricultural land acquisition by foreigners, reversing an earlier policy that welcomed Iranians (as well as others) to settle and invest in Georgia’s agricultural sector.

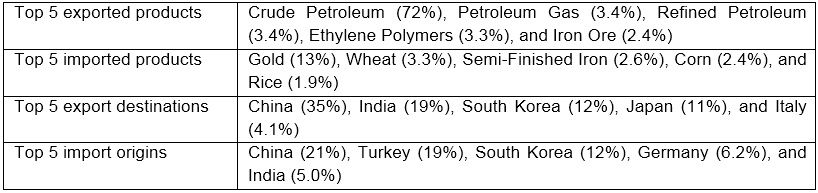

According to MIT Observatory of Economic Complexity, Iran’s trade is currently heavily tilted towards China, Teheran’s single most important trade partner, and other major Asian economies.

Table: Iranian trade structure, 2014

With the sanctions lifted in the near future, Iran is very likely to reorient a part of its trade to the West, and in particular, resume its once very strong trade connection with the EU. This is where the Caucasus, and Georgia in particular, comes into play as a trade hub between Iran and Europe. Georgia’s current economic relationship with Iran can only be described as operating well below its potential. According to the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat), Georgia’s exports to Iran as a percentage of total exports hovered around 1% from 2005 to 2014. Iranian FDI, having peaked in 2010-2012, has effectively dried out after Georgia’s unilateral decision to close its doors to Iranians and Iranian businesses. In 2013, Georgia hosted about 85,000 visitors from Iran; in 2014, their number was slashed in half following the re-introduction of visa restrictions.

Trade, Transport, and Tourism are vital pillars of the Georgian economy which would greatly benefit from a fast-growing Iran. Georgia and the South Caucasus provide a secure and efficient route to get Iranian energy to Europe, and European goods to Iran (and further East). In turn, the opportunity to access EU markets through the South Caucasus would prompt Iranian businesses to invest in Georgian infrastructure, helping implement ambitious rail, road, and sea transportation projects, upgrading the country’s transit and logistics capability.

"It's the new Dubai here" in Georgia, said a 25-year-old Iranian trader named Amin Akbari, when interviewed for the above-mentioned WSJ article back in 2013. While not quite a new Dubai, Georgia is a cheap and easy-to-reach destination for people from countries with strict laws on alcohol and gambling, such as Turkey, Iran, and conservative Muslim states in the Gulf. Further investment in the hospitality industry may help position Batumi and Tbilisi as a new “Eurasian Las Vegas.”

Another interesting opportunity for Georgia would be to deepen cultural ties, including the option of educational exchanges for Georgian and Iranian students. In fact, a government-sponsored program of educational exchanges might be a safe and respectable way to build stronger bilateral ties, which are critical for Georgia’s ability to profit from a change in Iran’s status. Iran will soon no longer be the Persian pariah that it once was, and Georgia should jump into this game before others beat them to it.