30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

05

April,

2021

Monday,

05

April,

2021

Monday,

05

April,

2021

Monday,

05

April,

2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives and perceptions in many important ways: the value we put on face-to-face interactions, the importance of personal space, communication with loved ones, and much more. Some of these perceptions and social changes may actually outlive the pandemic. During the prolonged lockdown periods, many people were suddenly confronted with the “hidden” side of their economic lives – the realities of unpaid care work. Unpaid care is something that people do daily to maintain their own and their family’s well-being: cooking, cleaning, shopping, paying bills, assisting, and caring for the elderly and children. Since people do these tasks for free for their household members, the value of such work does not get reflected in the GDP (hence, the “hidden” economic life). Have you ever considered how much of our working day is consumed by such activities? And – more importantly – who does this work in your family?

The latest time-use surveys performed in different countries tell the following story: worldwide, more than three-fourths, or 76.4% of unpaid care work is done by women, while 23.6% is done by men. In developed countries, women’s share in unpaid work is lower, at 65% (34.5% for men), while in emerging economies, 80.2% of unpaid care is done by women. One can see that even in developed countries women account for more than two-thirds of the unpaid household work. There is currently no country in the world where this burden does not disproportionately fall on women.

What does this actually imply for women? Because of taking on these unpaid care responsibilities:

1) Women get less free time (time for leisure of self-education than men)

According to 2018 time-use data from the UK, men enjoyed 5 hours more of leisure time per week than women. A Pew Research study found, on average, a similar 4.7-hour gap in leisure time based on the US data.

2) Women more often than men need to work part-time instead of full time

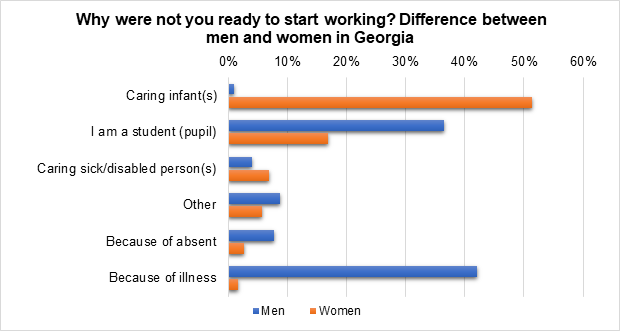

because of household responsibilities. They are also more likely to not work due to these responsibilities. Georgia’s 2019 labor force survey provides some insights. According to Georgian data, 22% of women report housekeeping, childcare, and elderly care responsibilities are listed as reasons for part-time employment. At the same time, only 1.4% of men report the same reason. Childcare or elderly/disabled care is listed as a reason for not being able to start work by 58% of respondent women, while the same was true only for 5% of men.

3) In addition, women get paid less even if they do engage in full-time and/or high responsibility work. In Europe, the “raw” gender pay gap (unadjusted for education and other characteristics) is around 15%, while in Georgia the corresponding gap is 17.7%. Adjusting for qualifications, personal characteristics, and for selectivity bias (the fact that better-educated women are the ones who tend to enter the labor market), there remains the “unexplained” portion of the wage gap between men and women 12% - this is the effect of discrimination or unobserved characteristics on the labour market. For Europe, the unexplained part of the gender pay gap is estimated to be roughly similar, at 11.5%.

The three points mentioned above imply that unequal work distribution is not just unfair to women – it is also bad for the rest of the society – men, children, families as a whole.

First, perception of unequal household work allocation is associated with lower relationship satisfaction, depression, and divorce (based on data from Sweden, US). Moreover, it is found that inequity in the distribution, rather than the amount of work causes greater psychological distress. Second, from the economic point of view “assigning” comparative advantage in household tasks based on gender alone creates significant economic inefficiencies in the society. Simply put, if a woman’s abilities are best suited for the labour market, but she is nevertheless forced (by social assignment) to devote a significant portion of her time to household work, society’s overall welfare will be lower. Last but not least, lower labour market participation for women and wage discrimination in the labour market means that women (especially single mothers or widows) are more likely to fall into poverty and stay poor, thus creating a vicious cycle of poverty and inequality for themselves, their families and children (for example, an ILO report indicates that 70% of working poor in the world are women). Other economic and social problems created by gender inequality are discussed in more detail below.

Some people might (and do) argue that a woman is “naturally” more attached to family and children that she is happier caring for family members than earning money. Due to these preferences (or sometimes due to educational choices), the argument goes, women either do not work or take on lower-paid jobs and thus let men specialize in earning a living for the family. If one simply asks women to evaluate the claims above, a different picture often emerges. In particular, surveys show strong support, globally, for more gender equality. In the US, both women and men state that they “prefer and expect to equally share paid and unpaid labor”. Moreover, according to one of the US surveys, 80 percent of children who had a work-committed mother see this as the best option, while slightly more than half of those with stay-at-home mothers see it as the best option.

In Georgia the attitudes toward “natural” home care roles for women are divided: according to CRRC survey, 44% agree with a statement that taking care of home and family makes women as satisfied as having a paid job. While 47% disagree with this statement.

One has to keep in mind that these attitudes and choices are very often not independent of gender norms, and how a woman’s role is perceived in society. Inequalities are often conditioned in early childhood. The skills we are taught as children often translate into our “comparative advantage” in adulthood. For example, according to a CRRC survey in Azerbaijan, around 96% percent of women were taught in childhood how to cook, clean the house or do laundry, while only 35% of men were taught how to cook and clean. In Georgia, close to 90% of women reported being taught how to cook clean, and do laundry, while less than 30% of men on average reported being taught these skills.

The attitudes towards’ female education and woman’s aptitude or right to work can determine the kind of jobs women can access as adults, and consequently influence the “comparative advantage” for household work. According to Human Development Report 2020 data, in Georgia, 18% of people exhibit educational bias (completely or somewhat agree with the statement that a university degree is more important for a boy), while around the world, this share is 26%. In the same time, 67% of people in Georgia exhibit economic bias (agreeing with the statements that men make better business executives or that men should have more rights to a job than a woman). Around the world, the share of people with this kind of bias is 57%.

Beyond a simple observation that women may not be “naturally” predisposed to domestic work, or are somehow inherently better at doing it, there are other considerations that make the inequality in the distribution of unpaid work unfair to women and bad for society as a whole.

So, why is it unfair if men and women “specialize” in the paid or unpaid types of work for the family? One of the simple answers has to do with a balance of economic power within families. The paid work is, undoubtedly, much more flexible than an unpaid one. Employees may choose to switch the company if compensation or working conditions are not satisfactory for them. This is not true for unpaid household work. A housewife effectively signs up for a lifetime job. Once she is in it, she has much less power to negotiate or renegotiate the terms of her “employment” and/or “switch jobs”. This is why women in many countries often find themselves vulnerable – having less say over the decision of the household, less influence over important decisions, including financial ones, less ability to be financially independent of their husbands, and less protected against domestic violence. Even women who work are paid less, and by earning less, receive smaller pension benefits than men. As already mentioned above, this makes single women, especially widows, single mothers more socially and economically vulnerable, facing higher poverty rates than men in similar circumstances.

The COVID-19 health crisis had a negative impact on unpaid care work. This was due mainly to reduced access to formal care services. Based on the experience of the USA, UK, and Germany, much of the additional workload during the lockdown period had fallen on women. Temporary closure of schools and emergence of online teaching generated a new domestic task for many families – home-schooling. This new task tends to be mostly the mother’s responsibility and increases the burden of the unpaid care work for women. Hence, working mothers spend less time on paid work and devote more time to domestic work, even if working mothers earn a higher income. The unpaid domestic work burden also increased more drastically for low-income households with more dependents.

On the positive side, flexible workload and/or working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic gave fathers an opportunity to spend more time on domestic work. Evidence from Spain suggests that the father became slightly more actively involved in household tasks, such as grocery shopping. Fathers in the UK also increased their participation in childcare – i.e. gender gap in childcare decreased from 31% to 27% in the country.

And a nationwide survey conducted in Turkey showed that in couple households, men’s domestic work time increased almost five-fold. The increase was highest for men who switched to working from home during the lockdown. These findings suggest that more flexible work arrangements for men can actually have a positive effect on the redistribution of household tasks.

Overall, there is so far mixed evidence of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the gender distribution of unpaid care work. At least in the short run, as reported in a study by Esuna Dugarova (2020), the positive shift in domestic work gender balance was observed in families where: (1) a man lost his job due to the lockdown, (2) a man was working from home or had flexible work arrangements, etc. and (3) a woman was working in healthcare of other essential services during the lockdown.

According to the UN Women survey, COVID-19 increased the burden of unpaid care work for both sexes, but more so for women. A higher percentage of women reported spending more time on cleaning (35% of women and 24% of men), cooking (31% of women and 25% of men), caring for children (61% of women vs. 44% of men). But overall, both men and women reported spending more time on at least one of the unpaid domestic work tasks (57% of women and 61% of men). Domestic workload particularly increased for households with children, most likely due to school closure. The survey, unfortunately, could not measure by how much the time spent on unpaid care work increased for men vs. women.

Yet, it is telling, perhaps, that 31% of women report a decrease in their leisure time, while only 23% of men did. A higher percentage of men than women increased their leisure time during the lockdown (30% of men vs. 21% of women). In the same time, there were no significant gender differences when it came to the number of paid hours worked (for salaried employees). These findings may suggest that the “double burden” was more likely experienced by women than men - women spent more time than men on unpaid and paid work combined.

To minimize the impact of COVID-19 on the increased care burden of women, policymakers may consider implementing support measures that focus on rewarding unpaid work. These measures could be:

Considering the high share of self-employment in Georgia, special efforts should be made to identify workers in the informal sector who were forced to leave their jobs due to higher family responsibility burdens during the pandemic.

However, what we listed above are only short-term measures aiming to reward an increased amount of unpaid work during the pandemic. In order to address the roots of the problem associated with unpaid work in the long term, a policy study by McKinsey Global Institute suggests that policy interventions should ensure recognition of unpaid work, reducing its amount and redistributing it between men and women.

In the Georgian context, the possible instruments could include the following:

In addition, the time of pandemic could be used as an opportunity to rethink/change social norms and gender stereotypes to support a more equal distribution of the burden of unpaid work between men and women in the future. During the lockdowns and curfews, many fathers take more child care and home-schooling responsibilities resulting in higher attachment to the children and experience of caring for children for longer periods. Also, as many boys are at home during the pandemic, parents have a good opportunity to teach boys about essential care tasks.

* * *

This blog has been produced within CARE Caucasus “COVID19 response and adaptation project”, funded by CARE International Emergency Relief Fund. The document has been created in close cooperation with ISET and CARE Caucasus teams. However, its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CARE International.