30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

18

February,

2017

Saturday,

18

February,

2017

Saturday,

18

February,

2017

Saturday,

18

February,

2017

Premise: I have to admit from the beginning that I am not married myself, thus what is written below is an outsider’s insights into explaining the phenomena of marriage.

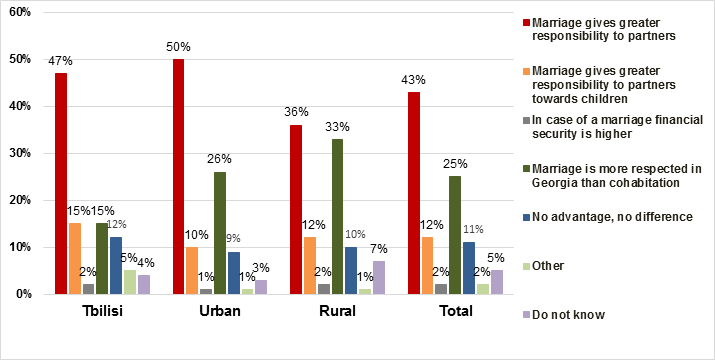

Marriage is a phenomenon strongly intertwined within our culture and everyday life. It is almost a “must do” thing in Georgian traditional society, and it has to be approved either by religious authority or by the state, or both. A recent study about Georgian youth entitled “Generation in Transition, Youth Study Georgia – 2016” by Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung, shows the 14-29 age cohort’s perceptions, awareness, and approaches towards marriage. The graph below presents the distribution of answers to the following question: what is the advantage of marriage over cohabitation?

According to Georgian youth, the two main reasons why official marriage is better than cohabitation are: first, it gives greater responsibility to partners (43%); second, marriage is more respected in Georgian society (25%). These two reasons are followed by a third explanation - marriage gives greater responsibility towards children (12%). It appears that marriage is perceived to be a better functioning mechanism than cohabitation when it comes to partners’ responsibilities and child-rearing. There is less pressure from society if you are officially married (and if you have already fulfilled your main duty – have children).

Why has marriage become such a solid part of our existence?

1. First of all, marriage is an institution, and a very old one. Institutions, according to Douglass North, are the "humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interactions." Constraints, according to North, are always devised as formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights) and/or as informal restraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, codes of conduct), which usually contribute to the perpetuation of order and safety within a market or society. Marriage, then, is an institution that is made up of many complex layers of formal and informal rules. They range from religious wedding vows to the laws regulating civil marriages. Moreover, behavior before and within marriage is heavily influenced by cultural norms (i.e. some cultures still have bride prices, dowries, and polygamy). However, despite all its possible variations, marriage as an institution has survived many centuries and is still a very important part of our everyday lives.

2. The fact that the institution of marriage has survived until today proves that it is very efficient. It means that marriage/family as an institution has strong survival characteristics relative to other methods of the organization trying to achieve the same purpose, and these survival characteristics are robust across time, locations, and cultures! Potential survival characteristics/gains mentioned in economic literature include the ability to exploit economies of scale or comparative advantage through specialization (Becker 1985), risk-sharing (Kotlikoff and Spivak 1981; Hess 2004), the production and consumption of household public goods, including one’s own offspring (Becker 1965), and the provision of credit (Cox 1987, 1990). None of these gains, however, are exceptional and exclusive to individuals in conjugal unions, and, therefore, they do not provide a solid rationale for the existence of marriage.

The basic family structure centers around one man and one woman. Families have proven to be a very efficient method of raising children and passing human capital from one generation to another. There have been attempts to raise children outside of families since the time of the ancient Greeks, yet in no case have they have survived. From an evolutionary biology point of view, an important survival feature of marriage is that it gives females (who bear the major cost of childbearing and child-raising), insurance against male abandonment. Some examples from the animal kingdom seem to be consistent with this point of view. In some species, females will not agree to copulate until males have constructed a nest for them – thus obliging them to make pre-copulation investments. In other species, females do not hurry to breed and take some time in order to spot signs of fidelity and domesticity in advance. Feminine coyness and prolonged courtship or engagement periods are very common among animals. Marriage seems to serve a similar purpose in the human kingdom.

But it is not only females who benefit from marriage. Bethmann and Kvasnicka (2011) present a very interesting aspect of marriage from the male’s point of view. They argue that marriage serves the fundamental purpose of mitigating the risks of mating market failure that arise from incomplete information on individual paternity. While one always knows who is the mother of a child, paternity may be doubtful. If we go back to the animal kingdom, in many species males enforce a period of prolonged courtship before copulating with a female, driving away all other males who approach her, and preventing her from escaping. This strategy assures him that the child will be his own, and to avoid being the unwitting benefactor of another male’s children.

So, marriage seems to serve a dual regulatory function in human society: on one hand, it gives insurance to females; on the other hand, it serves as a mechanism to cope with information asymmetry about individual paternity for males. Greater paternity confidence motivates more male parental investment in children. Different types of marriages ensure different levels of investment in children. Monogamy is considered to be the most efficient in this regard (Perry 2016).

3. Marriage always involves third parties, mainly the church and the state, who issue a “license” – right – to form a family. This “license” is usually of lifetime duration. Think of wedding vows like “till death do us part”! “Licenses” issued by the state give very concrete benefits like inheritance, ownership benefits, spouse’ legal rights, entitlements to various programs, surrogate decisions, child adoption rights, etc.

Apart from providing these benefits, licensing by third parties adds stability to the institution of marriage by raising the costs of divorce. Usually, these costs are very high in the case of religious weddings (for believers) and moderate when it comes to civil marriages.

The solidity of its survival features is very important for any institution. If evolutionary biologists and institutional economists are right, and reproduction, child upbringing, parental certainty, and female insurance are the main factors behind the survival of marriage, recent changes in technology and in the social environment may challenge the survival and effectiveness of this institution. Improvements in household technology and increased support from the state have been reducing childrearing costs. In addition, female labor force participation and employment rates have been increasing, and women have become more and more independent. Genetic paternity tests are now available and males can cope with the above-mentioned asymmetry of information about paternity issues at a relatively low cost. It is not surprising that starting from the second half of the 20th century, we have witnessed increasing divorce rates and increasing rates of cohabitation, as well as a growing number of single parents.

All these changes imply that society’s rationale for regulating the mating market through marriage is weakening. The above-reported Georgian survey data seem to already indicate the first signs of this change. While talking about marriage’s advantage over cohabitation, in fact, respondents put greater responsibility towards children at only 3rd place, below the alternative explanation that marriage is more respected in Georgian society.

I might be accused of not mentioning love and trust and other key aspects of romantic relationships. I am ignoring them on purpose as they constitute the basis not only of marriage but also of cohabitation and therefore – do not give marriage any advantage in this regard.

I would like to conclude this piece with one question that I find extremely interesting: will marriage, possibly our longest-lasting institution, survive all the recent changes in society, and overcome the profound challenges it is currently facing?