02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

10

June,

2017

Saturday,

10

June,

2017

Saturday,

10

June,

2017

Saturday,

10

June,

2017

In just a couple of weeks Baku is going to host the second Formula One Grand Prix in its history. Being in love with motor races and inspired by the fact that for the first time in my life I will attend such an important race (and the Land of Fire); I tried to explore the economic impact of hosting expensive international events for one’s country.

In 2017, the Formula One Championship will take place in 20 countries. Nineteen of these countries are either in the top 15 by the level of GDP, or are (net) oil and gas exporters. The only exception here is Hungary (which is not a net oil exporter and occupies 54th place in the world by GDP). Clearly, hosting Grand Prix is an expensive affair.

Why is a Formula 1 race so expensive?

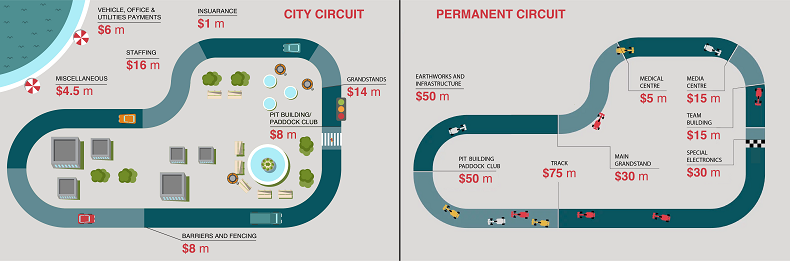

First, the host country needs a circuit which satisfies all the infrastructure and safety standards set by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). The total cost of building a typical permanent track is about $270 million. There is an alternative – to host a Grand Prix on a street circuit (as in Baku), which is cheaper and quicker to establish than a permanent circuit. Still, it requires repurposing streets, building barriers, grand stands and other facilitates. The annual cost of establishing such a circuit is around $60 million. Therefore, for a period longer than 6 years, the construction of a permanent track (with annual maintenance costs of up to $20 million) is more cost effective than having races in the city streets. Additional benefits of a permanent circuit are possibilities to host other racing and sport competitions, or even music festivals.

Second, all countries except Monaco pay annual hosting fees to F1 around $30-$40 million. This fee increases every year at a rate which depends on individual countries’ contracts.

Summing up all costs, a 10-year contract for a new host country results in up to a one billion dollar expenses. A huge amount, right? However, simply having enough money does not guarantee a Grand Prix in your country. F1 owners are not just interested in quick money, but also in a long-term development of their business and brand in the region.

“We end up with races in places like Baku in Azerbaijan where…it does nothing to build the long-term brand and health of the business. Our job is to find partners that…help us to build the product.” said Greg Maffei, chief executive of the new F1 owner, the Liberty Media Corporation.

Thus, despite a 10-year contract, the future of F1 in Baku is not clear. According to the Minister of Youth and Sports, the cost of Baku Grand Prix including all fees and infrastructure expenditures was approximately $100 million last year.

When it comes to benefits, the calculations are a little bit tricky. Direct revenues for race organizers are limited solely to ticket sales, while funds raised from broadcasting, merchandising, corporate client services or even from promo banners go to F1 owners' pockets. Direct revenues last year in Baku constituted only $2.6 million from selling 25 thousand tickets – mere pennies compared to the costs.

Given this, why on earth are so many countries keen to host Formula 1 Grand Prix? The answer is, because it puts countries on the global sporting map, and with its 500 million viewers, F1 is one of the best platforms to promote tourism. The 3-day broadcast of the F1 race is promoted by international TV channels, as well as numerous news and publications throughout the entire preparation period. Its long-term effect on tourism, however, is hard to estimate. It is much easier to calculate the immediate impact on tourism in the days of the Grand Prix.

For example, according to the study “Major Event Trust Fund Gain from the 2013 Formula One United States Grand Prix” (Don Hoyte, 2013), economic gains for the state of Texas were about $355 million. This included hotel, car rental, food, soft drinks, beer and wine, non-F1 entertainment, travel costs, event presentation expenses, corporate, sponsor and team spending and tax from ticket sales.

No such estimates exist for last year’s Baku Grand Prix, but considering the fact that only 25,000 tickets were sold and more than half of them were bought by Azerbaijani citizens (compared to 114,512 people who attended the race in Texas, of which 67% were from outside the state), the impact would be rather limited.

The same situation is expected this year, however, the occupancy rates of hotels in Baku (and hostels, guesthouses, and apartments), gleaned from a simple search on Booking.com, is significantly higher during the weekend of the Grand Prix – 72%, significantly more than the week before (40%) or the week after (48%). At the same time, hotels increased their prices, in some cases by five times.

Additional short-term impact on the economy is shaped through creating jobs for construction, communication, and organizational works. Without proper analysis it is hard to argue about the profitability of the event in Baku. Even less is known about the possible long-term impact of the 2017 F1 Azerbaijan Grand Prix on the country’s tourism and economic growth.

Azerbaijan started an active promotional campaign on an international level a couple of years ago, resulting in the following:

• A two-year sponsorship contract with Atlético Madrid in 2013-2015;

• The first European Games in 2015;

• The 4th Islamic Solidarity Games, May 2017;

• Baku has already won the right to host the European Youth Olympic Festival in 2019;

• Sponsorship agreement with UEFA signed in 2013: 4 matches as part of the European Football Championship in 2020.

Will these events prove to be a wise investment of public money? At this point, it is anyone’s guess. International experience is mixed, and one could argue that it is more proper for a country to exercise moderation, especially in the wake of oil price collapse a couple of years ago.

At the same time, Georgia is trying to achieve the same goal as Azerbaijan, but with modest expenditures. Just recently we had the honor of hosting TCR International Series in Rustavi International Motorpark (01-02 April 2017), where Georgian driver David Kajaia won the qualification and the first race.Georgia keeps focus on smaller scale events (concerts of famous singers like Robbie Williams, Aerosmith, Elton John, Batumi Jazz Festival; GEM Fest; World Rugby U20 Championship, etc.). These are cheaper and easier on the country’s budget. Still, the management of such events is a big issue - remember the problems with ticket sales of the UEFA Super Cup Final between Barcelona and Sevilla (August 11, 2015), or the unfulfilled promises to build ten rugby stadiums for the World Rugby U20 Championship? Most of these events are financed and organized by the state program “Check in Georgia” with a budget of 28 million lari in 2016, and a little bit less in 2017.

Still, the government might consider conducting proper cost-benefit analyses to have a clear understanding about the effectiveness of the program and its net economic effects. Finally, we, the citizens, need to decide – is it worth splurging money on infrastructure for expensive international events, or should we be satisfied with an occasional big-name concert on the Black Sea Arena – just for fun?